James Badham, UC Santa Barbara

Thousands of marine species with mapped locations worldwide remain largely unprotected, according to a new study by a team of international marine scientists, including UC Santa Barbara’s Ben Halpern. The research also shows that the United States ranks near the bottom in terms of supporting formal marine protected areas (MPAs) that could safeguard marine biodiversity.

The first comprehensive assessment of how much coverage MPAs provide for marine life worldwide examined the ranges of 17,348 species with known distributions, including whales, sharks, rays and fish. The findings appear in the journal Scientific Reports.

The researchers found that 97.4 percent of marine species have less than 10 percent of their range represented in MPAs. According to co-author Halpern, these species are likely representative of the protection status of all marine species. He noted that nations with the largest numbers of “gap species” — those whose range lies entirely outside of protected areas — include the U.S., Canada and Brazil.

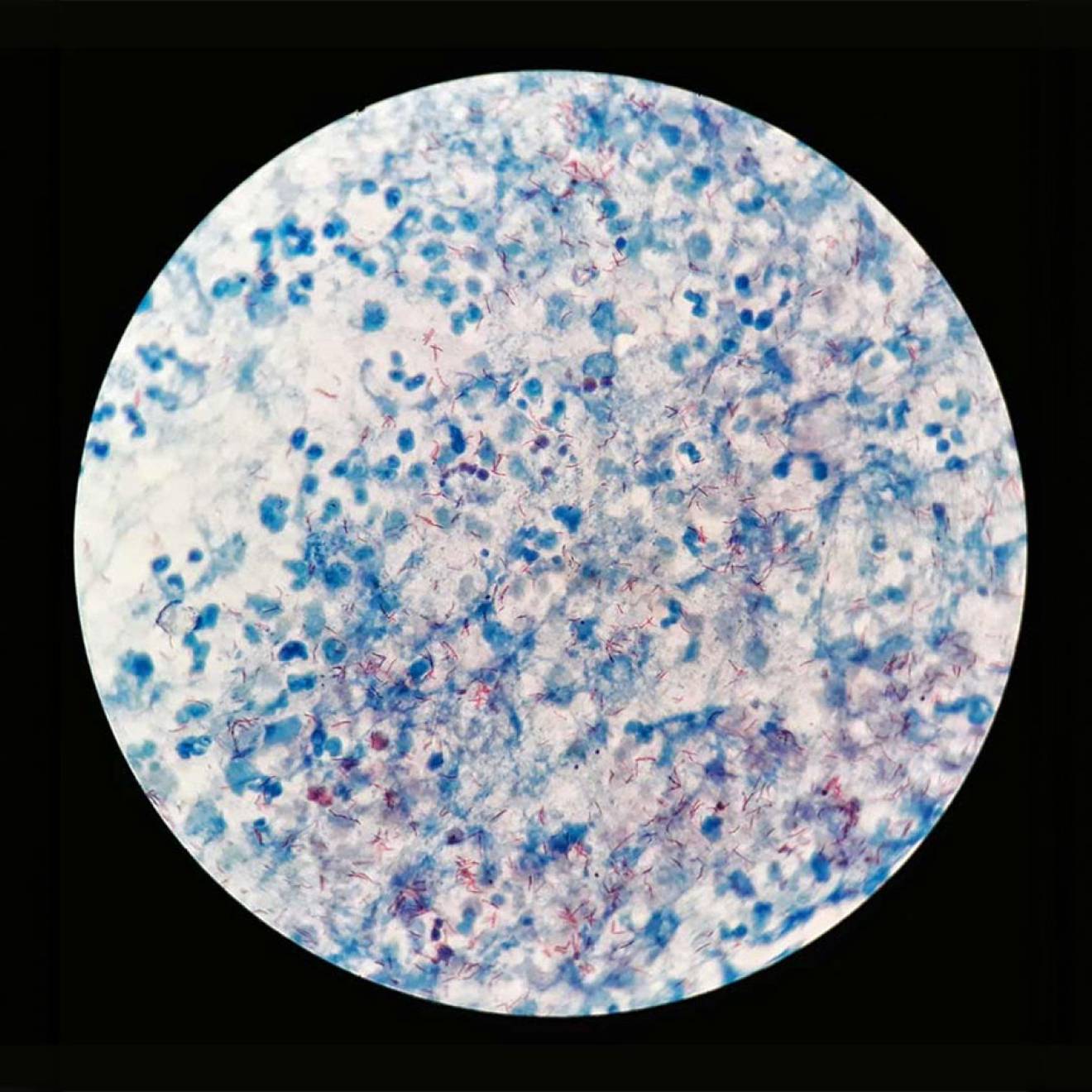

Credit: XL Catlin Seaview Survey

“The increase in the number of MPAs in recent years is encouraging, but most of this increase has come from a few very large MPAs,” said Halpern, a professor at UCSB’s Bren School of Environmental Science & Management and an associate of the campus’s National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis. “Those very large MPAs provide important value, but they can mislead us into thinking that biodiversity is being well protected because of them. Species all around the planet need protection, not just those in some locations. Our results point out where the protection gaps exist.”

The study’s findings spurred the investigators to outline opportunities for achieving the conservation goal set by the Convention on Biological Diversity of protecting 10 percent of marine biodiversity by 2020. For example, the majority of species considered very poorly represented (with less than 2 percent of their range in MPAs) are found in exclusive economic zones — ocean areas over which a state has special rights regarding the exploration and use of marine resources. This suggests an important role for individual nations in better protecting biodiversity.

“The process of establishing MPAs is not trivial, as they impact livelihoods,” said the study’s lead author, Carissa Klein of the University of Queensland in Australia and a UCSB alumna who earned her master’s degree at the Bren School in 2006. “It is essential that new MPAs protect biodiversity while minimizing negative social and economic impacts. The results of this study offer strategic guidance on where MPAs could be placed to better protect marine biodiversity.”

The study underscores the imperative that new MPAs be systematically identified, taking into account what has already been protected in other places as well as the socioeconomic costs of implementation, the feasibility of success and other aspects of biodiversity such as endemism — species unique to a defined geographic location — and extinction risk.

“As most marine biodiversity remains extremely poorly represented, the task of implementing an effective network of MPAs is urgent,” noted co-author James Watson of the Wildlife Conservation Society and the University of Queensland. “Achieving this goal is imperative not just for nature but also for humanity, as millions of people depend on marine biodiversity for important and valuable services.”