Elizabeth Salaam, UC San Diego

This story was published in the Fall 2023 issue of UC San Diego Magazine.

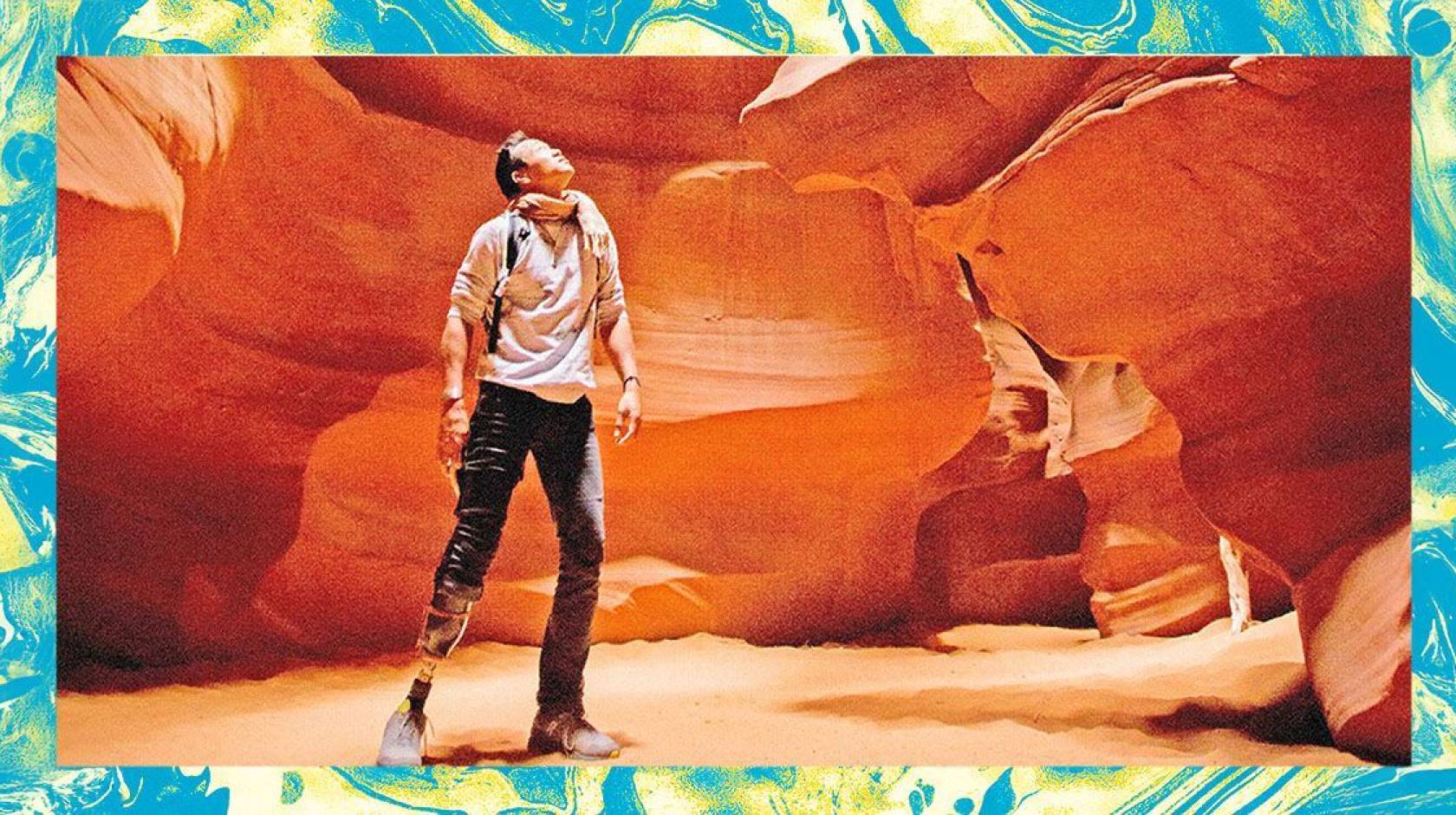

The story of psychedelics research at UC San Diego does not begin with research scientist Albert Yu-Min Lin, but it is certainly a good place to start.

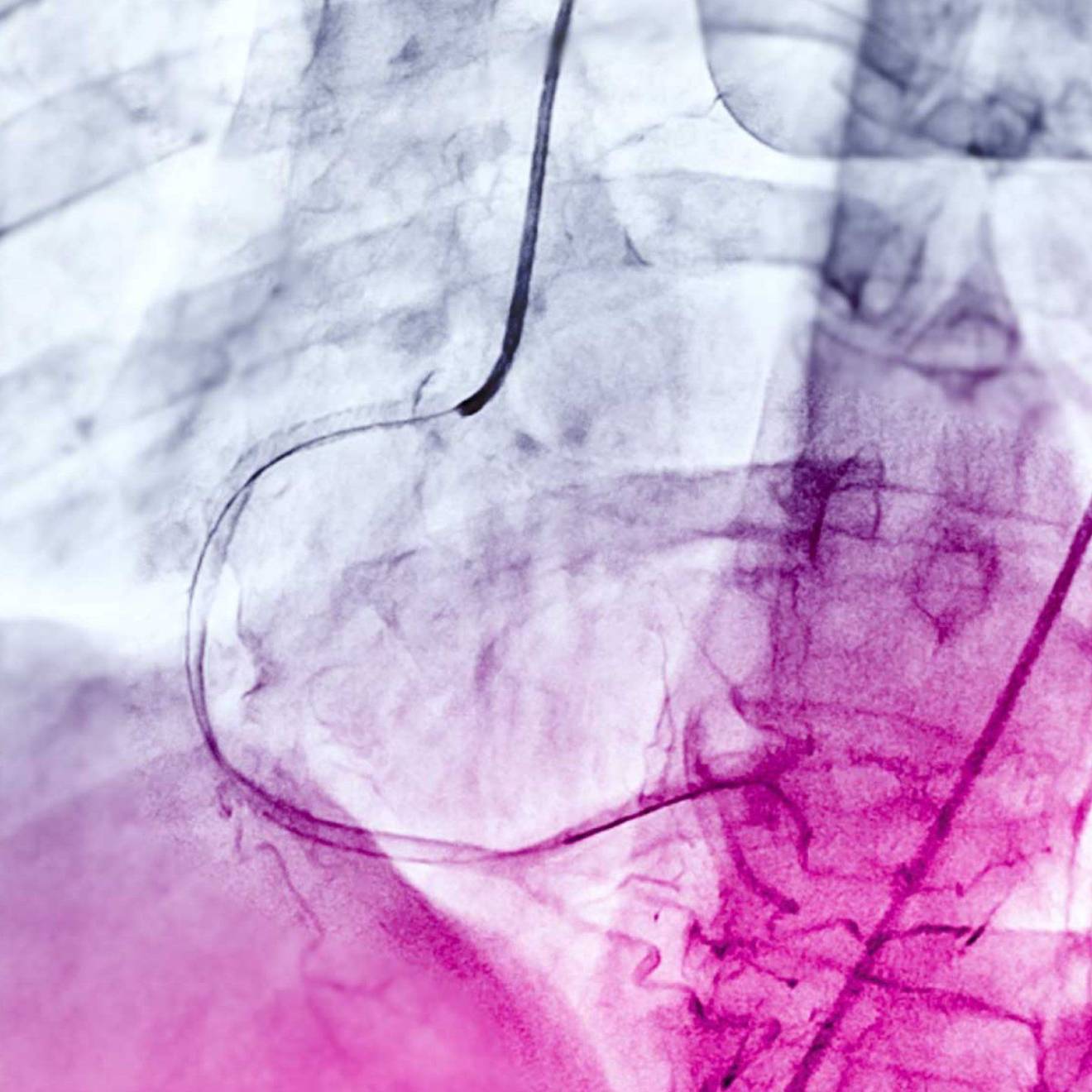

In 2016, the world-renowned scientist, National Geographic explorer and three-time UC San Diego graduate (’04, MS ’05, PhD ’08) suffered a devastating accident that resulted in the amputation of his lower right leg. After the physical wounds healed, Lin was left with excruciating and debilitating “phantom limb pain.”

He describes the sensation as the feeling of “my leg folding in half and breaking into bones and lighting on fire and knives stabbing into it … but there was no leg there.”

Lin had recently read about successful studies using psychedelics in the treatment of depression and anxiety. Desperate and willing to try anything, he drove to the desert to try psilocybin, the active compound in “magic mushrooms.”

He says, “If our mind is how we perceive the world, and our mind can also perceive our bodies in that context, then maybe I should be looking into the tools that are used to treat other aspects of the mind.”

A single session with psilocybin alleviated his pain in less than 30 minutes. After weeks of all-consuming and debilitating pain that had him on the brink of extreme depression, Lin felt like himself again.

His psychedelic experience changed everything.

But until then, the use of psilocybin to treat phantom limb pain had not been researched in a controlled, rigorous way. According to the National Institutes of Health, phantom limb pain affects an estimated 60% to 80% of amputees.

The pain is usually the worst in the first six months after amputation, with episodes lasting anywhere from brief seconds and minutes to hours of continuous pain with no relief. The chance of developing depression, anxiety and suicidal thoughts increases significantly, and opiate abuse is common.

Before resorting to psilocybin, Lin had worked closely with Tim Furnish, chief of pain medicine at UC San Diego Health. They tried a range of different treatments to ease his suffering, including standard nerve pain medications, opioids, antidepressants, ketamine and medical marijuana. The one thing that showed promise was mirror visual feedback, a therapy introduced by V. S. Ramachandran, UC San Diego psychology professor emeritus. The therapy tricks the brain into letting go of the pain. When using the mirror, Lin’s pain would subside — however, the results were temporary and the moment the mirror was removed, his pain came rushing back.

Furnish could not have been more surprised when Lin said the psychedelic mushrooms had eliminated his pain. And although it did return after a few hours, the intensity seemed to have decreased dramatically.

“There’s not a lot drugwise that can take pain to zero, especially when it’s severe and becoming chronic,” says Furnish.

Soon after, under Furnish’s guidance, Joel Castellanos used Lin’s case study as the jumping off point for his fellowship research paper, “Chronic Pain and Psychedelics: a review and proposed mechanism of action.” The highly cited paper has helped to galvanize a new era of psychedelic research at UC San Diego.

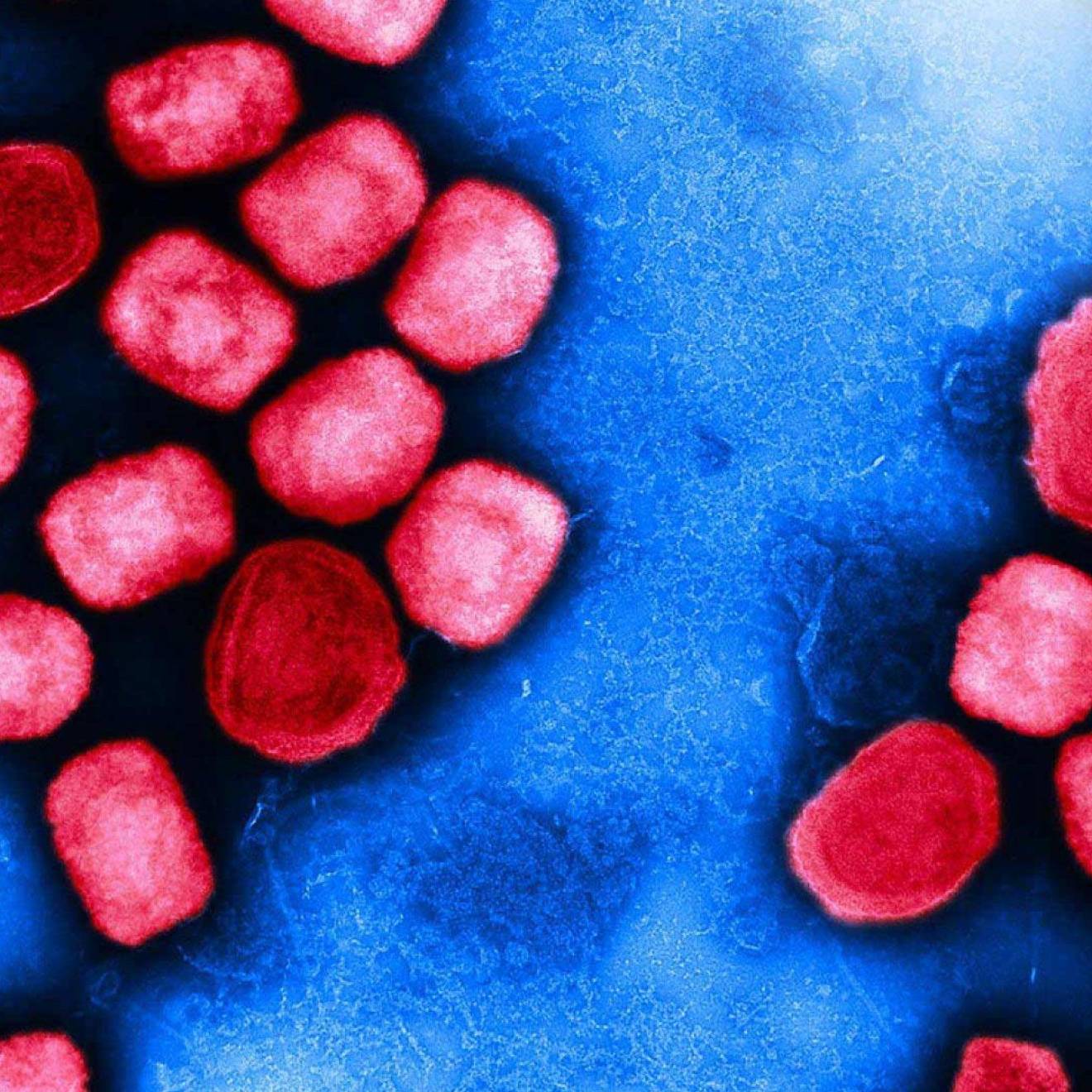

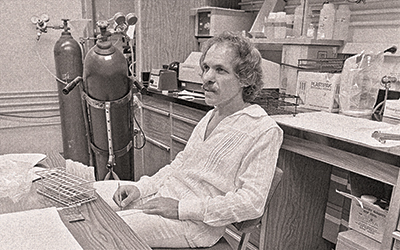

Research on classical psychedelics, including LSD, DMT, mescaline and psilocybin, began at UC San Diego 50 years earlier in the lab of Arnold J. Mandell, the founding chair of the Department of Psychiatry. His area of expertise revolved around psychedelics and theories surrounding the genesis of psychosis.

In 1970, a young Mark Geyer arrived as a graduate student and joined Mandell’s lab. But one year later, decades of research across the country came to a halt due to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) classifying psychedelic compounds as Schedule I drugs, or “drugs with a high potential for abuse and no currently accepted medical use.”

However, animal studies were still allowed under strict supervision. Mandell and Geyer, as his student — and, later, lab partner — were authorized to continue their work.

In 1983, Geyer secured his first grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

“I couldn’t get money from the mental health institute because they had decided that we couldn’t learn anything about mental health from psychedelics,” says Geyer. But his lab could get funding to study drugs with a high potential for abuse. The National Institute on Drug Abuse continued to fund his work for 33 years.

And yet it’s tricky to model the hallucinogenic effects in animals.

“We can’t really study these things phenomenologically because if they can’t talk to us, we can’t understand their experience,” says Geyer.

In response to this conundrum, he created the Behavior Pattern Monitor system to help researchers use behavior cues to study the effects of altered consciousness in the mammalian brain. The system has strong translatability to human models and has also helped to inform the concept of “set and setting” (or one’s mindset and physical social environment), which is especially relevant for human psychedelic studies.

In 2007, Adam Halberstadt joined Geyer’s lab as a postdoctoral fellow and invented a device to assess the “head twitch response,” a rapid head-shaking behavior induced by psychedelic drugs in mice.

“If I give a mouse a drug, I can predict whether it will act as a psychedelic in humans by monitoring whether the mouse shows head twitches,” says Halberstadt.

Because of the accuracy and efficiency of Halberstadt’s process for assessing potency, more than a dozen outside companies run their new psychedelic compounds through his lab for assessment before moving into clinical trials.

Geyer and Halberstadt spent decades in relative obscurity while laying the groundwork for psychedelic research in human subjects. By the time Lin lost his leg in 2016, Geyer had been retired for three years. But he returned to work for the chance to bring psychedelic research mainstream.

In the early 1970s, Mark Geyer, PhD ’72 joined the lab of Arnold Mandell (pictured), founding chair of the Department of Psychiatry, to study psychedelics including LSD, DMT, mescaline and psilocybin.

“Albert’s persuasive reporting of his experience was striking and impressive and felt very tangible, very real,” says Geyer. “It motivated us to gather a group and consider doing clinical psychedelic research at UC San Diego.”

The work is both novel and groundbreaking, potentially offering relief to those who suffer from phantom leg pain, while also addressing a worldwide drug crisis: opioid abuse and dependence.

“There’s a huge need for a medication that would produce long-term pain relief,” says Halberstadt. “This is one case where if psychedelics could work, it would really be a game changer.”

In 2018, the FDA designated psilocybin a breakthrough therapy, and in response, Patrick Coleman and colleagues from the UC San Diego Arthur C. Clarke Center for Human Imagination organized a new collaboration across campus to launch the Psychedelics and Health Research Initiative (PHRI). The interdisciplinary group included the Center for Human Frontiers at the Qualcomm Institute and the Departments of Anesthesiology and Psychiatry at UC San Diego School of Medicine, as well as campus clinicians and researchers from the fields of psychiatry, psychology, pain medicine, mindfulness and others who saw the potential to advance psychedelic research to promote healing and manage pain.

Mind Manifested

“In light of the opioid epidemic, it is paramount that we begin to research how natural and nonaddictive products (such as psilocybin) can be used to alleviate suffering,” says Fadel Zeidan, associate professor of anesthesiology and mindfulness expert whose pain research involves extensive brain imaging.

In 2011, Zeidan published a groundbreaking paper in the Journal of Neuroscience depicting the first-ever images of a brain in a meditative state. And later through clinical trials, he proved that mindfulness meditation significantly reduces pain and changes the structure and functionality of the brain.

“Pain modifies consciousness and so does mindfulness. And so do psychedelics,” says Zeidan. “The brain imaging and clinical diagnostic methods I use for meditation easily translate to doing psychedelic research.”

Brain imaging studies such as Zeidan’s have shown that exposure to psychedelic drugs promotes neuroplasticity, or the ability of neural networks in the brain to change through growth or reorganization. Based on those existing findings, psilocybin may be effective against phantom limb pain because it causes new functional brain connections and pathways to form in regions of the brain supporting self-image and the experience of pain.

In February 2021, PHRI received a $1.3 million grant from the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation to fund a clinical trial investigating the therapeutic potential of psilocybin in treating phantom limb pain.

The blind, placebo-controlled study is led by Principal Investigator Halberstadt and co-investigators Zeidan, Furnish, Castellanos, Geyer, and Cassandra Vieten, a clinical professor of family medicine and public health.

Study subjects receive either psilocybin or a dose of niacin (vitamin B3), which mimics some of the physical sensations experienced with psilocybin but does not produce a hallucinogenic “trip.” The trial involves clinical visits to assess pain and psychological functioning, magnetic resonance brain imaging and a “day of” six-to-eight hour psilocybin treatment in the company of therapists trained for psychedelic sessions.

“Our study will help us understand how psilocybin impacts the experience of chronic pain and thus recommend its use as a potential alternative to opioids,” says Zeidan.

The Road Ahead

In July 2023, PHRI was renamed the Center for Psychedelic Research, a newly approved academic center at the UC San Diego School of Medicine.

“Science indicates that psychedelics have the potential for treating various medical and mental health disorders and promoting social outcomes such self-transcendence, empathy and compassion,” says Vieten.

In the last 15 years, significant evidence has shown how classical psychedelics such as psilocybin, can be used to treat depression, anxiety, addiction and other psychological disorders.

And as a nonaddictive alternative to opioids for pain conditions, psychedelics represent a revolutionary and much-needed improvement for more than 100 million sufferers in the U.S. alone, as estimated by the Centers for Disease Control.

“We plan for our center to conduct multiple clinical trials assessing the psychophysiological mechanisms of how psychedelics might promote health and well-being,” says Vieten, who is leading the formation of a consortium of psychedelic research centers at multiple University of California campuses to leverage their combined resources.

The goals of the new center are multifunctional. In addition to running clinical trials, the center aims to establish a rigorous training program for scientists.

Center leadership includes original members of PHRI: Mark Geyer, PhD, director; Adam Halberstadt, PhD, pharmacology director; Fadel Zeidan, PhD, neuroscience director; Cassandra Vieten, PhD, psychology director; Tim Furnish, MD, medical director; Joel Castellanos, MD, associate medical director; and Jon Dean, PhD, DMT research director.

No doubt, UC San Diego is well-positioned to lead the next era of psychedelic research.

“Pain is a very tricky thing,” says Lin, who has been free from phantom limb pain for five years. “My experience opened a window into the power of the mind to do extraordinary things — to shift the perspective of pain, to potentially remap it — and if that can help others, it was all worth it.”

To support psychedelic research at UC San Diego, visit giving.ucsd.edu/health-medicine