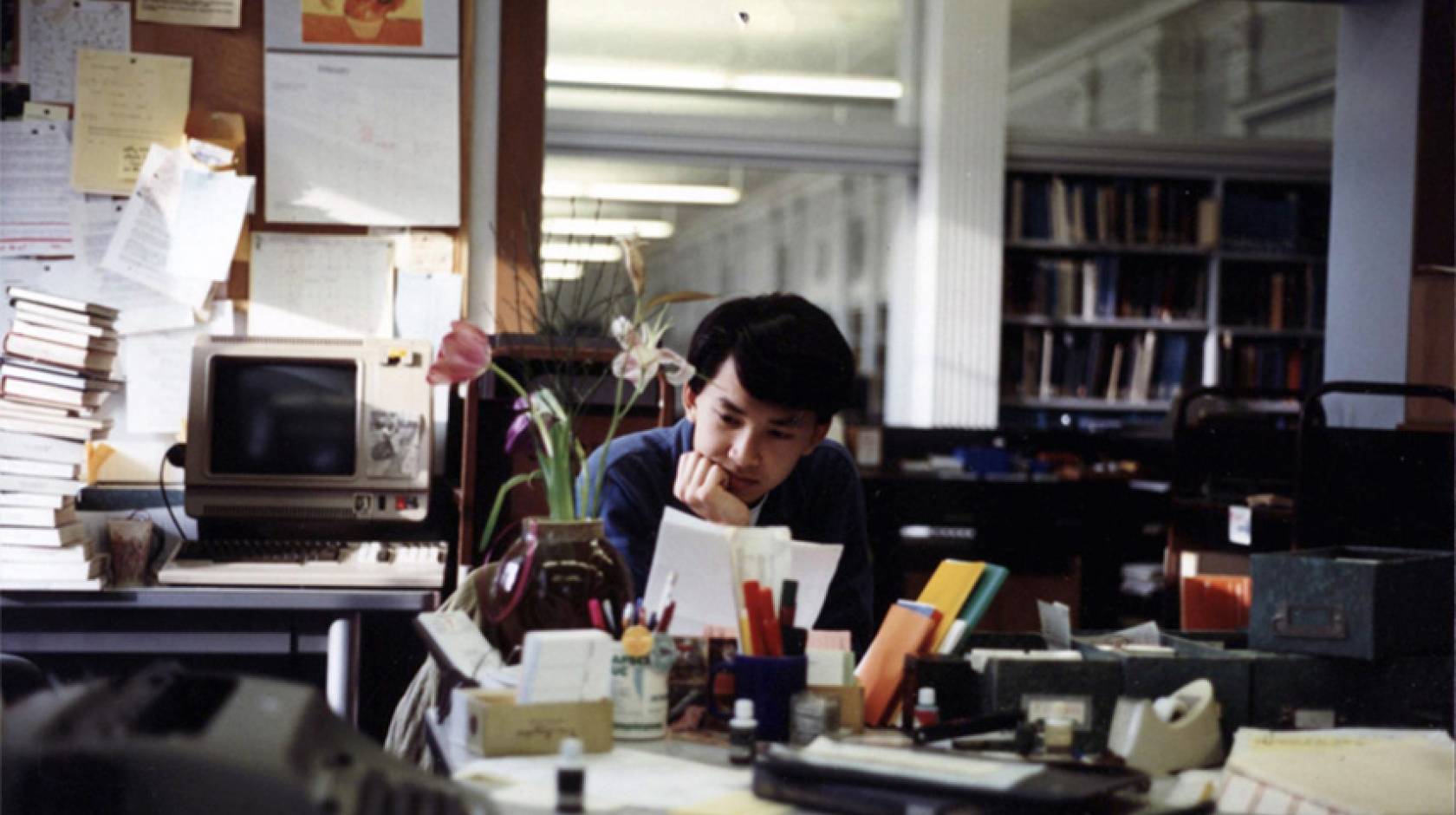

Tor Haugan, UC Berkeley

Viet Thanh Nguyen emerged from UC Berkeley with more than a diploma. In fact, he earned three (but who’s counting?) — dual bachelor’s degrees in English and ethnic studies in 1992, and a doctorate in English in ’97.

But his education wasn’t confined by the walls of a classroom.

Nguyen became steeped in activism, leaving Berkeley with “four misdemeanors, three diplomas, two arrests and an abiding belief in solidarity, liberation, and the power of the people and the power of art,” he recalls in his memoir, 2023’s A Man of Two Faces.

As a student, Nguyen worked in the Social Welfare Library, now known as the Social Research Library, in Haviland Hall. Nguyen recalls having conversations with Craig Alderson, who has worked at the library for more than four decades. Alderson was among the “radical people” Nguyen had met at Berkeley, with strong political convictions and a heart for making a difference in the world.

“Berkeley was the start of an emotional journey for me into maturity,” Nguyen reflected in a recent interview with the UC Berkeley Library. “It was also the start of a political journey for me — both journeys I’m still on.”

Alderson remembers Nguyen as “serious, studious and careful, but also a sweet guy and good conversationalist with a sense of humor.”

“He always impressed me as a true embodiment of the adage, ‘Still waters run deep,’” Alderson says.

Nguyen is now a professor of English, American studies and ethnicity, and comparative literature at the University of Southern California and a celebrated writer. His debut novel, The Sympathizer, earned the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 2016. An HBO limited series based on the book premieres Sunday, April 14.

We recently caught up with Nguyen to talk about his time at UC Berkeley, his go-to spots on campus, the importance of libraries, and the class at Cal that “radicalized” him.

In your memoir, A Man of Two Faces, you talk about taking an Asian American history course and being “immediately radicalized.” I wanted to learn a bit more about your experience in activism at UC Berkeley and how Berkeley shaped or expanded your social consciousness.

I visited Berkeley as a tourist before freshman year. The very atmosphere of Telegraph Avenue and the campus just immediately felt like home to me, coming out of San Jose. (Nguyen’s family fled Vietnam in 1975, after the fall of Saigon, and eventually settled in the Bay Area.)

Once I transferred to Berkeley and started taking classes, it felt like something clicked, intellectually and politically.

The class was with Professor Ronald Takaki — Introduction to Asian American History, I believe. It did radicalize me because it exposed me to a whole history of Asian Americans in the United States that I’d never heard of before. And that was the gateway to becoming an ethnic studies major.

At the same time, I wanted to be involved in campus life, so I joined various organizations. The one that really vibed with me was the Asian American Political Alliance, a community of like-minded, young, passionate Asian American students who cared about politics. We did everything from running campaigns for student government to forming coalitions with other student activist groups to protesting things that we thought were unjust on the campus.

I got a broad exposure to campus activism very quickly. It was utterly transformative.

How did Berkeley shape you as a writer?

I took a lot of literature classes at Berkeley, both in the English department and in ethnic studies.

I had gotten a very good canonical education in my high school, but it was mostly an education into the Western classics — white American classics. It wasn’t really until Berkeley that I started reading Asian American, African American, Chicano and Native authors, and authors from other countries who were engaged in anti-colonial art and politics. Encountering anti-colonial writers of color in the United States was crucial in giving me a sense that the kind of writing I wanted to do, and needed to do, could be connected with my own history, my parents’ experiences, politics, the war — all that kind of stuff.

I also was trying to learn how to write, and I was taking writing classes with Maxine Hong Kingston, Bharati Mukherjee and Alfred Arteaga. That was really the first systematic training that I got in writing.

Did you know at the time how special it was to be instructed by luminaries like that?

I had some sense of it. I certainly knew the professors were famous and important. But as I signaled in the memoir, I was also kind of an arrogant, ambitious young person and was not fully appreciative of everything that I was exposed to. My experience with my professors was really, really crucial. But it would take me maturing to really understand what they had gone through and their sacrifices as writers and as teachers.

Now I’m a teacher with 25-plus years of experience. As I mentioned in the book, I fell asleep in Maxine Hong Kingston’s class every day. So when I look out at my own students, and sometimes they fall asleep, I’m like, “OK, I get it.” I’m not going to embarrass them or call them out, because people have complex lives. Also, people who are 20 years old have a lot of maturing to do, as I definitely did.

When you were a student, did you have any favorite libraries, hangout spots, or study spots on campus or beyond?

A lot of the activism was happening at Eshleman Hall. (Eshleman Hall was demolished in 2013. The rebuilt Eshleman opened in 2015.) We spent a lot of time there, just hanging out, socializing, studying, and planning activities.

We would study in our apartments — I had a very crowded apartment south of campus — and at the cafes, like Milano. The library that I hung out at the most was the Moffitt Undergraduate Library. A lot of late nights there.

Your first big break was from the San Jose Public Library — an award for Lester the Cat, which you wrote in the third grade. Can you talk about the importance of libraries in your life?

As a young person in San Jose, I didn’t have any books in my house. My parents just didn’t have any books, and I didn’t have any money to buy books. I got my own job probably at 16 years of age. But before then, I relied on the public library for all my reading material. The library was my entryway into the world. I couldn’t leave San Jose, but I could leave it through the library.

The university libraries were where I started to do serious research. By the time I finished my undergraduate studies at Berkeley, I’d written three theses, which required spending a lot of time in the carrels and collecting books and becoming very familiar with certain call numbers.

My carrel was beneath ground in Doe. That place was funky. You’d just wander the stacks, doing your own thing, and see fleeting glimpses of other students doing their thing. It was so mysterious, the kind of intellectual pursuits we were all engaged in.

The combination of activism and what I was getting from my professors in the classroom, but then also what I was doing for myself by delving into the library — all of that was really crucial for transforming me not only into a scholar, but a writer as well, because a lot of that material would eventually make its way into my fiction and nonfiction.

Viet Thanh Nguyen