Kat Kerlin, UC Davis

More than 48,000 deer, thousands of Pacific newts, close to 100 mountain lions and many thousands of other animals are killed each year by vehicles on California roads, according to the 2024 “roadkill report” from the University of California, Davis’ Road Ecology Center.

The 11th annual report, “Roadkill, A Preventable Disaster,” notes that about more than twice as many deer die from vehicle collisions each year in California than from hunting. Collisions are responsible for more than 10% of deer deaths each year, as the state’s total deer population has been dropping for decades. The report said roadkill may be partly responsible for their overall decline.

Roadkill is also expensive. Wildlife-vehicle collisions, or WVCs, cost California more than $200 million every year. Yet those costs are slightly lower in recent years than previous years — in part because of the decline in mule deer, the most frequently hit large animal.

“Anytime you get a reduction in roadkill, people think it’s a good thing,” said Fraser Shilling, director of the UC Davis Road Ecology Center, a program of the Institute of Transportation Studies. “But it’s often not. In this case, it’s because there are fewer deer and other animals to hit.”

No newts is bad news

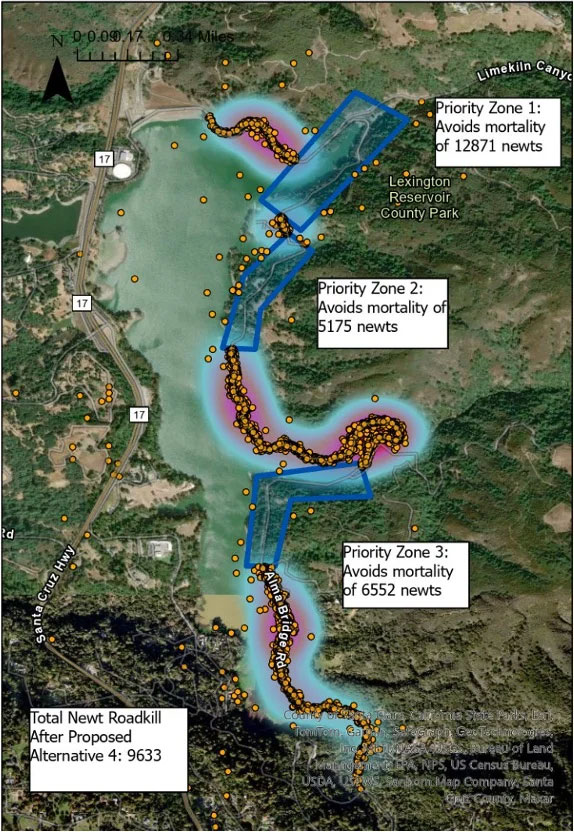

Another dramatic loss is occurring among California newts and rough-skinned newts on Alma Bridge Road in Santa Clara County. There, the largest known population of these newts is being killed by the thousands every winter as they attempt to cross the road from their forest floor home to Lexington Reservoir to reproduce. About 5,000 newts are killed each year on this road.

“Roadkill is a preventable natural disaster,” said Shilling. “When a road is flooded, or there’s a landslide, state and local agencies act immediately to get the road fixed and reopened. That shows transportation agencies can move fast in a natural disaster. The crashing newt population is a natural disaster and deserves the same kind of rapid response.”

The Road Ecology Center has worked in the past with scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey and Santa Clara County to find ways to prevent further decline of the newt populations. The report describes a potential solution proposed by the county that could elevate Alma Bridge Road in three sections to prevent about 70% of the newt deaths. Additional approaches could include reducing traffic spilling over from Highway 17, moving traffic away from hot spots, or closing the road to nonresidential traffic during newt-crossing times (typically when it rains).

“Our worst fears that this delicate newt population is spiraling toward extinction are sadly becoming a reality,” said Sofia Prado-Irwin, a staff scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity. “Newts, pumas and other wildlife desperately need more crossings and wildlife-friendly development before it’s too late. Improving wildlife connectivity will lead to safe coexistence, increased climate resilience and a world where California’s wonderful biodiversity can continue to thrive.”

Roadkill hot spots

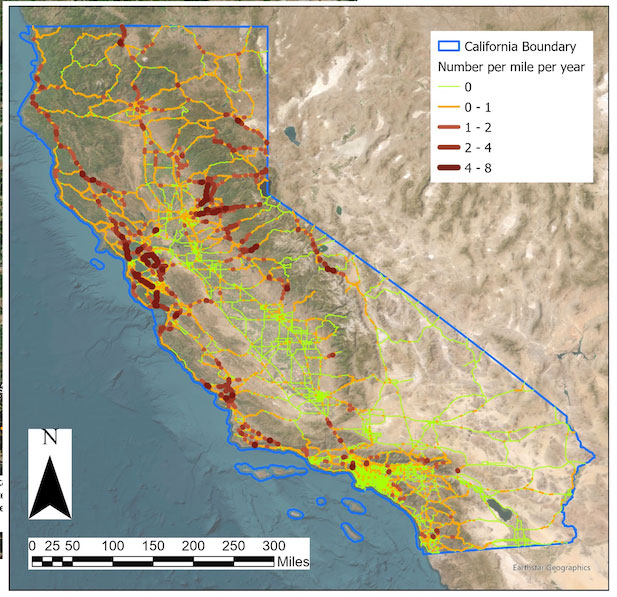

Drawing from nearly 53,000 traffic incidents involving wildlife, 162,000 carcass observations reported to the California Roadkill Observation System, or CROS, and other roadkill reporting systems between 2009 and 2023, the report identified 627 roadkill hot spots that could benefit from wildlife crossings and fencing.

The state’s top hot spots for roadkill — where the rate and costs of wildlife-vehicle collisions are highest — consistently include:

- I-680 in Contra Costa and Alameda counties

- I-280 on the San Francisco Peninsula

- U.S. 101 in Marin County

- U.S. 50 in El Dorado County

- S.R. 17 in Santa Cruz County

- S.R. 49 in Placer and Nevada counties

Mountain lions and momentum

A minimum of 613 mountain lions were reported killed by vehicles between 2016 and 2023. Actual figures are likely higher, as there is no requirement to report vehicle collisions involving mountain lions.

Mountain lions in Southern California are expected to benefit from the world’s biggest wildlife crossing, the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing, when it opens in 2026. Shilling said such efforts have opened the door to broader public and state support for wildlife crossings. He applauded recent state efforts, such as the Safe Roads and Wildlife Protection Act, for restoring wildlife movement. The act allocated funding during the 2022-23 legislative session for additional wildlife crossings.

“We highlight and give kudos for the dramatic increase in wildlife fencing and crossing planning that the state has engaged in the last two years,” the report states. “Fencing remains the only way to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions at the state scale.”

The research in this report was funded by the U.S. Department of Transportation through the National Center for Sustainable Transportation, the Institute of Transportation Studies at UC Davis, the Wildlife Conservation Network, and Pew Charitable Trusts.

The authors acknowledge the efforts of thousands of volunteer observers who have contributed to the California Roadkill Observation System over its 15 years, as well as state and agency staff members who report on wildlife-vehicle collisions. These efforts have created the largest roadkill reporting system of its kind in the United States, with more than 200,000 observations of more than 400 species.

Subscribe to the Science & Climate newsletter

Media Resources

Media Contacts:

- Fraser Shilling, UC Davis Road Ecology Center, fmshilling@ucdavis.edu

- Kat Kerlin, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-750-9195, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu