Julia Busiek, UC Newsroom

A career in medicine was about the furthest thing from Marco Angulo’s mind at the end of high school. He’d scraped together enough credits to graduate — “barely,” he says now — but class had always felt like a distraction from his dream job: playing guitar in a rock and roll band.

A lot of kids grow up with the same dream. But for a while at least, Angulo made good on it. He left home in Montebello, east of Los Angeles, and for the next eight years, he odd-jobbed around Hollywood during the day while playing a full schedule of shows with his band, the alt-rock group Romantic Torture. They had a devoted following in mid-1990’s L.A., drew decent crowds, even cut an album.

But by age 26, Angulo was broke, tired, all hustled out. “I hit rock bottom,” he says. With no idea what came next, he started taking classes at East L.A. College.

It was the start of an improbable journey that would take Angulo through a bachelor’s degree at UC Berkeley and medical school at UC Irvine. He was a member of one of the earliest classes to graduate from UC PRIME (short for Programs in Medical Education), an approach to medical education at the University of California designed to fix the state’s health care disparities by growing the state’s physician workforce and training doctors who’ve gone on to work in communities facing health care shortages and challenges.

This year, we’re celebrating the 20th anniversary of UC PRIME. Since the first class started at UC Irvine in 2004, the program has expanded to every UC medical school campus and graduated nearly a thousand physicians who’ve taken on specialized coursework, hands-on clinical care, research and service, all focused on health equity.

“Our graduates go on to be excellent providers for patients who’ve been let down by the system,” says Charles Vega, M.D., director of PRIME-LC (Programs in Medical Education for the Latino Community) at the UC Irvine School of Medicine. “They’re also starting and leading clinics, or trying to get public policy changed, or mentoring upcoming doctors. They’re great clinicians who are also changemakers and leaders.”

From burned out to fired up

In his first term at East L.A. College, Angulo signed up for a Chicano studies class, “almost by accident, just trying to meet my general education requirements,” he said. The class gave him a new way to think about the disparities in his Latino community in East L.A., where too many people struggled to find decent housing, healthy food, regular health care and stable employment.

“I used to think, ‘Well, that’s just my community,’” he says. But as he learned more about the history and policies that shaped his neighbors’ fates, he started to realize that many of their struggles were symptoms of broken or badly designed systems, not expressions of individual character or choices. “Nobody grows up saying, ‘You know, I’d rather be houseless, I’d rather not have documents, I’d rather be sick,’” Angulo says. “There are problems with the way we’ve set things up.”

Angulo redirected the dedication that had powered his career as a musician into his classes. He transferred to UC Berkeley, loading up on science courses while earning a bachelor’s degree in Chicano Studies, thinking he might want to go into health care. At his professors’ urging, he started to consider a career as a doctor.

Dr. Charles Vega, director of PRIME-LC at the UC Irvine School of Medicine

As he started studying for the MCAT, Angulo caught wind of PRIME-LC. The program was in its earliest days at UC Irvine, thanks to the vision of the school’s senior associate dean, Dr. Alberto Manetta. Manetta, who passed away in 2022, knew Latinos in California had long experienced disproportionately high rates of chronic illness such as heart disease, liver disease, obesity and Type 2 diabetes. Part of the problem, Manetta reckoned, was with California's physician workforce: the standard medical curriculum didn't have much to say about the social and structural causes of disease. And while Latinos make up about 40 percent of California's population, they represented just 6 percent of its doctors. So Latino patients had slim chances of encountering a provider who spoke their language and truly understood their culture, and as well as the society-wide systems and forces that affect their health. Manetta thought UC Irvine’s medical school could be part of the solution.

“Dr. Manetta wanted to support students, especially from the Latino community. He wanted to give them extra skills in addition to the standard medical curriculum, so they’d be better able to go back and serve in Latino communities and start reducing these chronic health disparities,” says Vega. Manetta’s vision became reality in 2004, when the first class of students enrolled in PRIME-LC at UC Irvine.

Dr. Alberto Manetta, whose vision lead to the creation of UC PRIME. Dr. Manetta passed away in 2022.

“I was like, Oh my god, that’s my program. That’s exactly what I want to do,” Angulo says of his decision to apply. Again, he made good on his dream: he got in, and in 2011, he graduated with the third cohort to emerge from PRIME-LC.

Over a decade into his career as a family medicine physician, today Angulo says he’s “living the dream.” He’s medical director for the Institute for Health Equity at AltaMed in Los Angeles, California’s largest federally qualified health center. He supervises dozens of physicians and other providers. He also leads research into health inequalities among L.A.'s Latino community, and he launched AltaMed’s family medicine residency training program four years ago.

20 years of fighting for a healthier California

The model of medical education developed at UC Irvine 20 years ago has been so effective at recruiting physician leaders like Angulo that the State legislature has funded more programs that follow Irvine’s lead, says UC Associate Vice President for Academic Health Sciences Deena Shin McRae, M.D. Building on the success of UC Irvine’s model of improving health care for California’s Latino community, PRIME now spans 10 programs across six UC campuses.

Graduates from these programs are easing California’s physician shortage and primary care gaps. Of the most recent graduating class of PRIME students, 42 percent pursued primary care, and 82 percent are doing their residencies in California. “That’s far higher than the retention rate for California medical students overall. So PRIME is doing a good job of identifying and training the students who really are dedicated to staying here to serve California,” McRae says.

Each UC PRIME program was created to serve a specific population that experiences health disparities in California, including rural residents, Indigenous people and people experiencing homelessness. And each program aims to enroll students who understand their patients’ backgrounds and cultures and want to fix the systems that contribute to health care disparities.

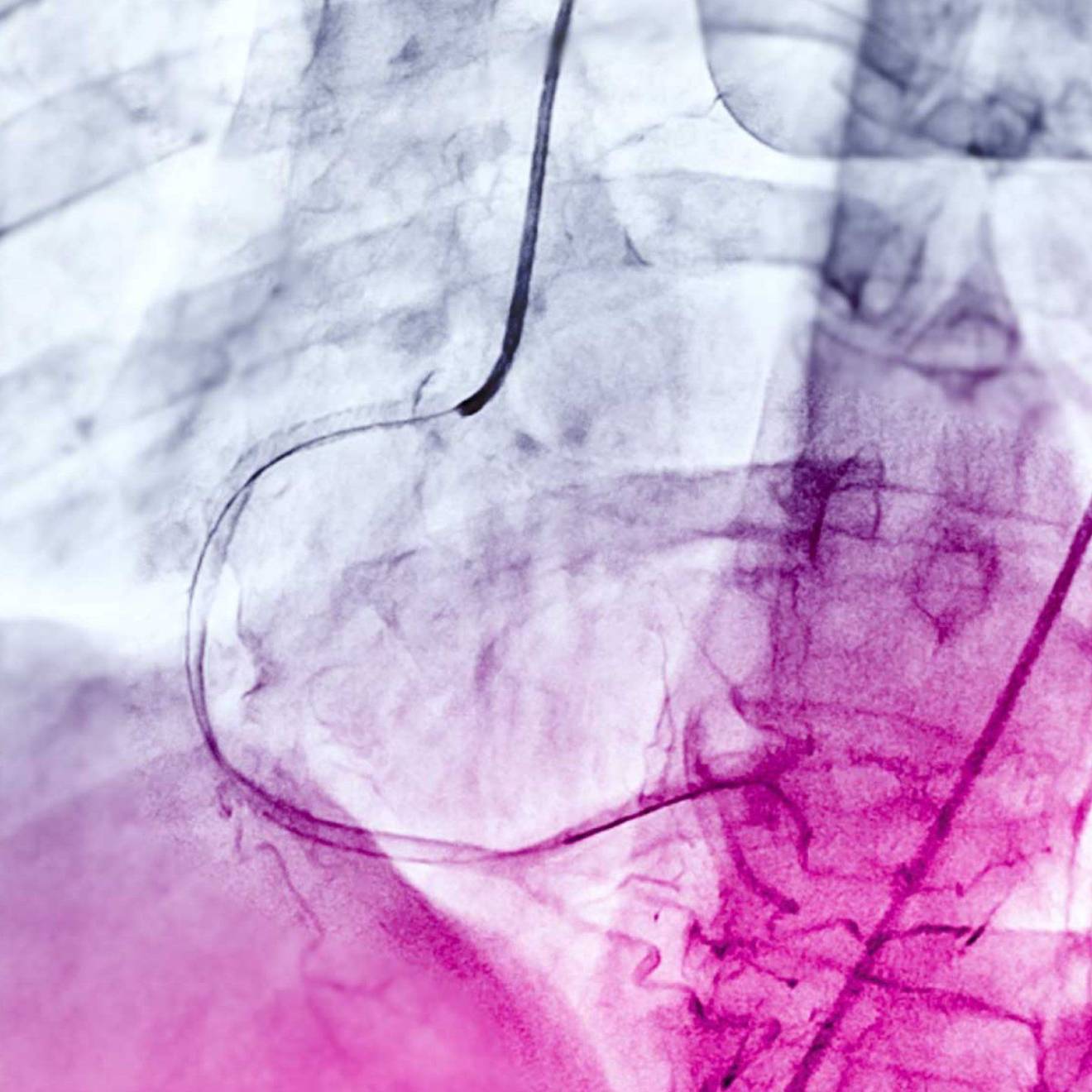

“What I bring from my time as a medical student is that ability to reflect with a patient and say, ‘Ok, you’re here for a non-healing wound, but what is it that brought you here today?” says Jesus Ulloa. He graduated from PRIME-LC alongside Angulo in 2011, and today he’s a vascular surgeon at Greater Los Angeles Veterans Affairs. “What are the barriers that are keeping you from getting the care you need so this doesn’t happen again?’”

Angulo says that growing up in a Latino community in East L.A. imparted a perspective and a language that have helped him provide better care to the patients he serves today. But the most important thing, what he falls asleep thinking about, is his drive to fix what’s broken and improve care for those who need it most. And that drive can come from anywhere.

“It doesn’t matter who you are, what your background is, or where you came from,” says Angulo, who helps interview future physicians applying to UC Irvine’s PRIME-LC program. “If you’re dedicated to serving this community, I can tell if your heart is in it right away. And that’s who we choose.”