Stephen McNally, Julia Busiek, UC Newsroom

Drive along California's Pacific Coast Highway and you'll catch some of America's most iconic views. But you’re just as likely to catch yourself turning your car around and heading back the way you came.

The 71-mile section of highway between Carmel and San Simeon is a legendarily scenic drive, but the dramatic topography also makes it hard to keep the road intact: landslides and washouts have closed Highway 1 through Big Sur dozens of times since the road first opened in 1937. A landslide in Februrary 2024 covered the road at an area called Regent's Slide; another stretch of road crumbled off a cliff at Rocky Creek a month later, temporarily stranding about a thousand people and their cars between the two landslides. Caltrans now estimates the highway won't fully reopen until sometime in 2025.

So why does this highway keep failing, and can anything be done to stop it?

A brief history of California plate tectonics

“The West Coast is still active geologically,” said Gary Griggs, professor of Earth sciences at UC Santa Cruz. “It's a place where tectonic plates have collided. We've got active faults” — most notably, the 800-mile-long San Andreas Fault, which forms the boundary between the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate.

For more than 20 million years, Griggs explains, these two colossal chunks of the Earth’s crust have been grinding slowly past each other along a mostly straight line, running northwest to southeast. Between Monterey and Cambria, though, a branch of the San Andreas Fault jogs horizontally at a spot called the Big Sur Bend. The plates can’t grind past each other as easily, so pressure builds up in the kink.

The result is steeper cliffs, bigger peaks, and a total mess of rock types all ground and churned and pressed together. “Almost like a rock hitting your windshield, you get a lot of cracks. It doesn't fall apart, but it cracks,” said Griggs. “And that's what the earth is like in there, it's just really broken up.”

In the late 18th century, the Portolá expedition walked up the coast from Baja California. “They came up through San Diego, what’s now Orange County, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara. It was rough going, but the terrain was at least doable,” Griggs says. “Then they got up around Cambria, and they looked up the coast to the north and saw these huge mountains coming up straight out of the ocean. They basically said, ‘Forget it, we will never get past those steep cliffs,’ and headed inland to the Salinas Valley.”

Later Spanish settlers looked down the coast from their vantage on the Monterey Peninsula and called this area “El Grande Sur,” or “the Big South.” Big Sur’s tortured topography continued to rebuff much in the way of European and American development for the next 250 years.

“It wasn’t until the Great Depression and the New Deal in the 1930s when they were really looking for big infrastructure projects that they somehow managed to get that road through there,” Griggs says. “But it was a slog to build, and it’s been a challenge to keep open ever since.”

Climate change is accelerating erosion

Big Sur has always been a volatile place, but geology isn’t the whole picture. Griggs says conditions are getting worse, thanks to humans.

To build the highway, engineers dug out loads of dirt and rocks, which reshaped the ground and made some sections weaker. And in recent years, Big Sur — like many places in California — has been battered by climate change. Wildfires have charred the vegetation and exposed the soil on steep slopes. Supercharged winter storms blow in from Pacific and get wrung out on Big Sur’s towering slopes. Without plants to absorb these atmospheric rivers' rainfall, the ground turns into a muddy mess. Those same storms generate towering waves that pound and erode the coastline.

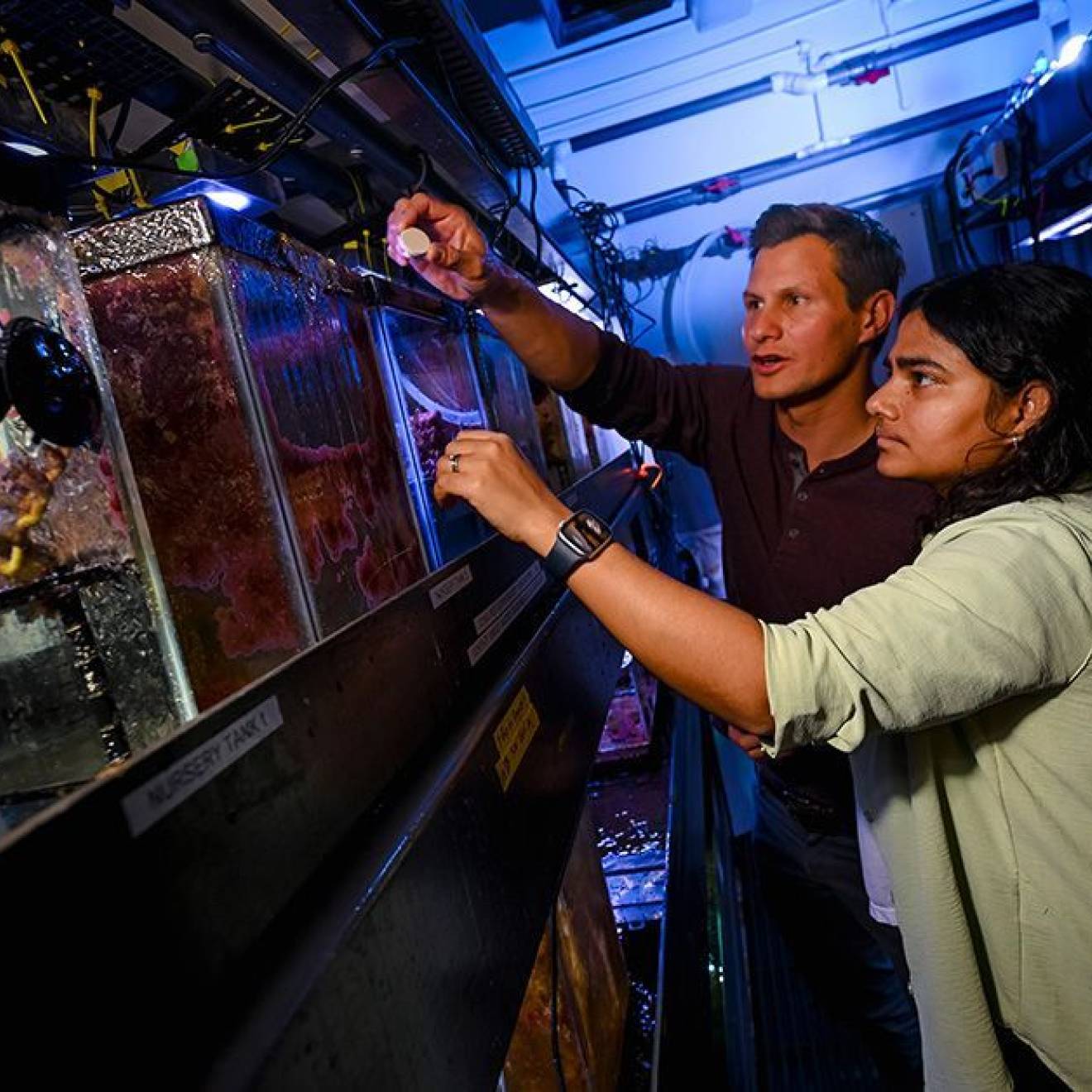

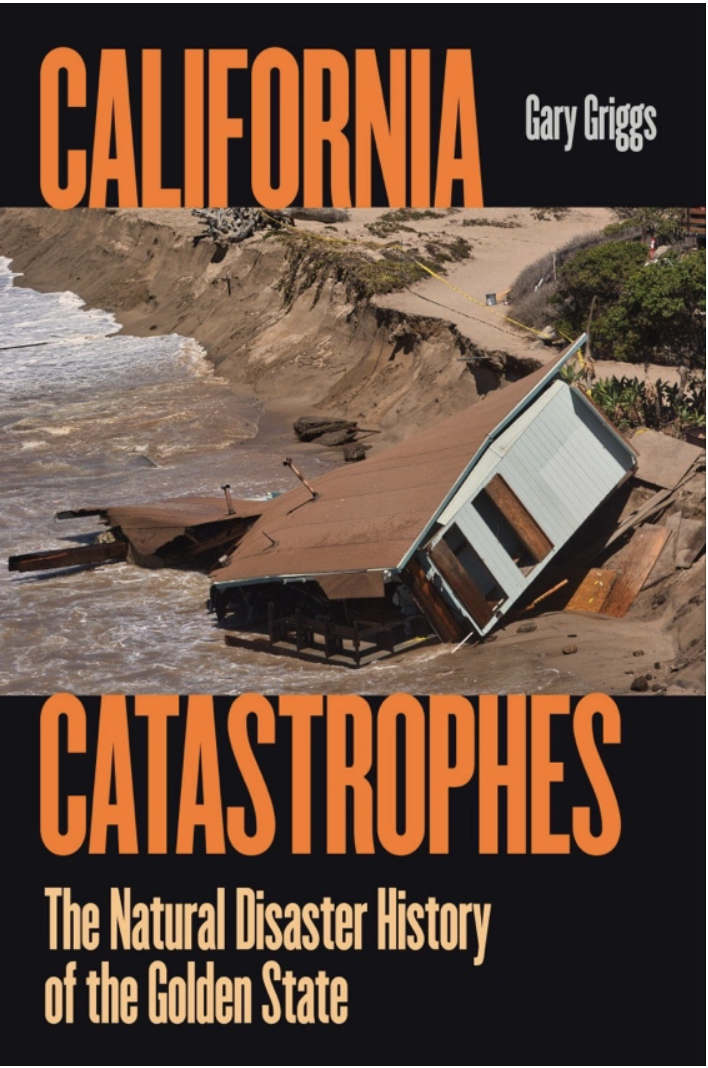

UC Santa Cruz Earth sciences professor Gary Griggs

Add all of that together and you have a recipe for landslides. “They happen so often down there that CalTrans has given them names,” Griggs says. “There’s McWay Creek, Rat Creek, Paul’s Slide, Rocky Creek, Vortex Slide, Pitkin's Curve, Grandpa's Elbow, Willow Creek, Hurricane Point … These are places that they’ve had to fix over and over.” Griggs visited the village of Big Sur in 1973, shortly after a storm on the heels of a wildfire unleashed a mud flow that buried most of the town up to its eaves. “But the ones most recently have been real massive,” he says.

At Mud Creek, CalTrans had long kept an eye on a section of hillside that was slowly slumping seaward. But the combination of wildfires and big storms seemed to speed everything up. In 2017, Mud Creek unleashed 6 million cubic yards of rock, wiping out a quarter mile of the highway. Cleaning up that disaster took more than a year and $54 million.

What can we do to keep Highway 1 open?

If you're wondering about a permanent solution, you're not alone. Big Sur has ardent fans the world over, and all those millions of visitors account for an estimated 90 percent of the local economy. And for the few thousand people who live here full-time, the route is their lifeline.

Costly and exasperating as maintaining this highway might be, “It's so important to so many people, I can’t imagine the State ever saying, ‘No, we’re not going to do this anymore,’” Griggs says. Can anything be done to slow down the landslides or keep the highway open more often?

“People propose building a tunnel, but it’d have to be about 75 miles long, and it would be prohibitively expensive, and you don’t get to see anything cool while you’re driving through it,” Griggs says. Another common suggestion? Move the road inland. “Yeah, we did that. It’s called Highway 101 and it runs down the Salinas Valley,” Griggs says.

Griggs favors treating Big Sur like any other major tourist destination and charging an entrance fee to generate enough money for cleanup. “Some of these big slides cost $50 million to fix. Somewhere between 5 and 7 million people travel that road in a typical year when it's open; if every car pays $10, that would go a long way in covering the repair costs,” Griggs says.

Going forward, it may be more a matter of adjusting our expectations. The few thousand people who live along the Big Sur coast full-time have seen the highway open and close and open again, and most are in the habit of stocking up on essentials in case of stranding. “The people that live there, they understand it, they live there knowing it's pretty rough,” Griggs says. “They know it's always been basically a temporary highway.”

Professor Griggs's latest book delves into the forces of nature that shape California’s geography, ecology and culture, and how the state can pull together to prepare for the disasters yet to come. Read a conversation with the author