Lisa Marie Potter and Nicholas Weiler, UC San Francisco

A new study led by a UC San Francisco sleep researcher supports what parents have been saying for centuries: To avoid getting sick, be sure to get enough sleep.

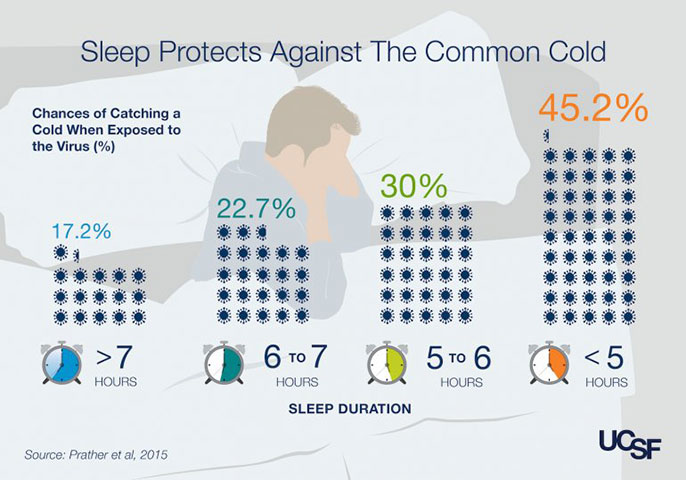

The team, which included researchers at Carnegie Mellon University and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, found that people who sleep six hours a night or less are four times more likely to catch a cold when exposed to the virus, compared to those who spend more than seven hours a night in slumber land.

This is the first study to use objective sleep measures to connect people’s natural sleep habits and their risk of getting sick, according to Aric Prather, Ph.D., assistant professor of Psychiatry at UCSF and lead author of the study. The findings add to the growing evidence of the importance of sleep for our health, he said.

“Short sleep was more important than any other factor in predicting subjects’ likelihood of catching cold,” Prather said. “It didn't matter how old people were, their stress levels, their race, education or income. It didn't matter if they were a smoker. With all those things taken into account, statistically sleep still carried the day.”

The study, “Behaviorally assessed sleep and susceptibility to the common cold,” appears online and in the September issue of the journal Sleep.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention call insufficient sleep a public health epidemic, linking poor sleep with car crashes, industrial disasters and medical errors. According to a 2013 survey by the National Sleep Foundation, one in five Americans gets less than six hours of sleep on the average work night, the worst tally of the six countries surveyed.

Scientists have long known that sleep is important for our health, with poor sleep linked to chronic illnesses, disease susceptibility and even premature death. Prather’s previous studies have shown that people who sleep fewer hours are less protected against illness after receiving a vaccine. Other studies have confirmed that sleep is among the factors that regulate T-cell levels.

Testing the ability to fight off the cold virus

To learn how sleep affects the body’s response to a real infection, Prather collaborated with renowned Carnegie Mellon psychologist Sheldon Cohen, Ph.D., the study’s senior author, who has spent years exploring psychological and social factors contributing to illness. Cohen’s group gives volunteers the common cold virus to safely test how these various factors affect the body’s ability to fight off disease. For this paper, Prather approached Cohen about investigating sleep and cold susceptibility using data collected in his lab’s recent study, in which participants wore sensors to get objective, sleep measurements.

“We had worked with Dr. Prather before and were excited about the opportunity to have an expert in the effects of sleep on health take the lead in addressing this important question,” Cohen said.

Researchers recruited 164 volunteers from the Pittsburgh area between 2007 and 2011. The recruits underwent two months of health screenings, interviews and questionnaires to establish baselines for factors such as stress, temperament, and alcohol and cigarette use. The researchers also measured participants’ normal sleep habits a week prior to administering the cold virus, using a watch-like sensor that measured the quality of sleep throughout the night.

The researchers then sequestered volunteers in a hotel, administered the cold virus via nasal drops and monitored them for a week, collecting daily mucus samples to see if the virus had taken hold.

They found that subjects who had slept less than six hours a night the week before were 4.2 times more likely to catch the cold compared to those who got more than seven hours of sleep, and those who slept less than five hours were 4.5 times more likely.

“It goes beyond feeling groggy or irritable,” Prather said. “Not getting sleep fundamentally affects your physical health.”

Sleep as a public health issue

The study shows the risks of chronic sleep loss better than typical experiments in which researchers artificially deprive subjects of sleep, said Prather, because it is based on subjects’ normal sleep behavior. “This could be a typical week for someone during cold season,” he said.

The new data add yet another piece of evidence that sleep should be treated as a crucial pillar of public health, along with diet and exercise, the researchers said. But it’s still a challenge to convince people to get more sleep.

“In our busy culture, there’s still a fair amount of pride about not having to sleep and getting a lot of work done,” Prather said. “We need more studies like this to begin to drive home that sleep is a critical piece to our wellbeing.”

Other contributors to the study were Denise Janicki-Deverts, Ph.D., of Carnegie Mellon University and Martica H. Hall, Ph.D. of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. The research was supported by grants from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Heart, Lung, & Blood Institute.