Roy Rivenburg, UC Irvine

When the lights go down in UC Irvine’s Sleep Center, things can get a little strange. Although some of the overnight patients simply snore like lawnmowers, others sleepwalk, scream or act out dreams by kicking, pedaling and punching.

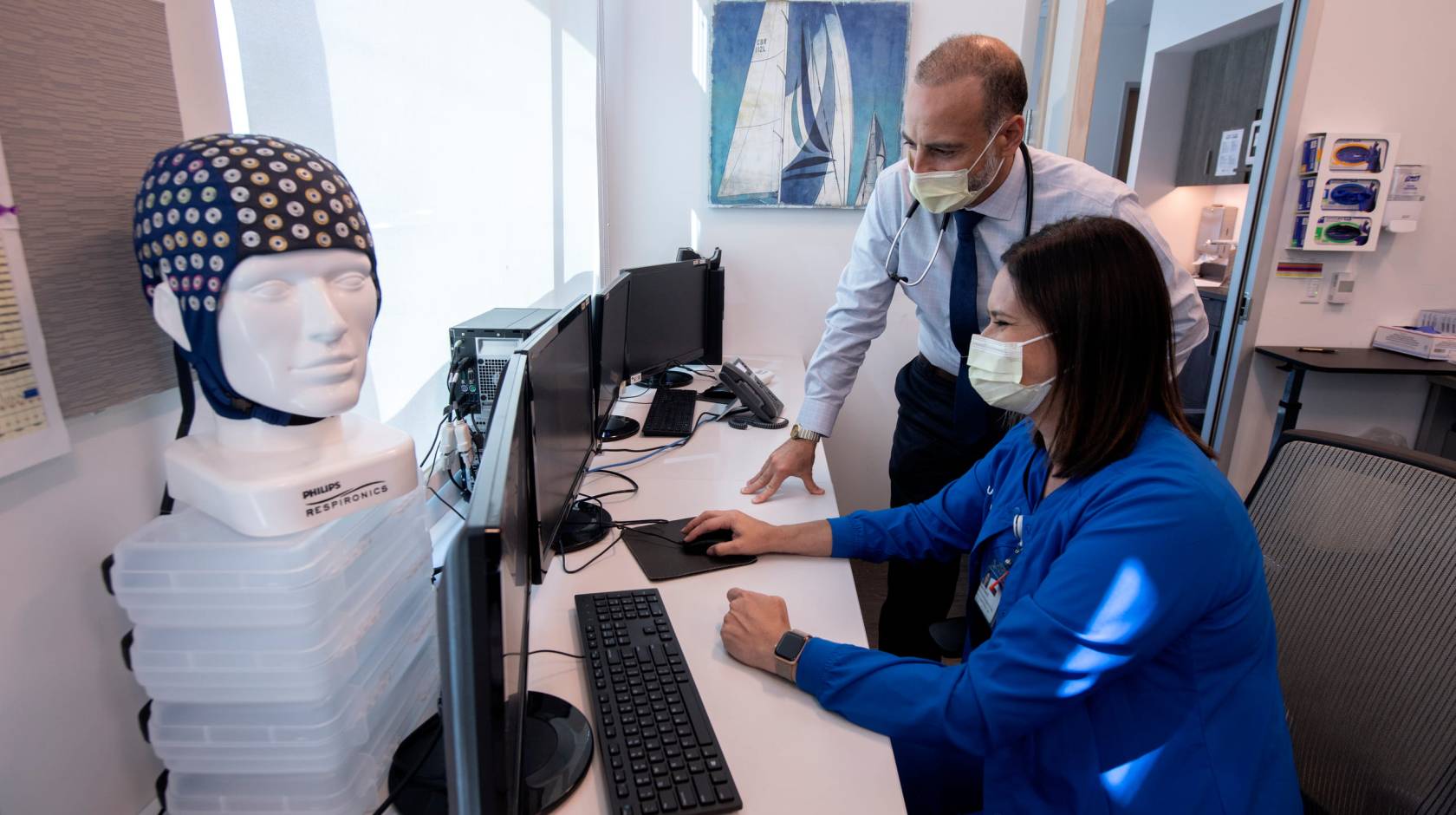

To diagnose such symptoms, technologists in the Newport Beach lab’s control room observe video feeds from the clinic’s eight high-tech bedrooms and track more than 30 vital signs for each patient, including brainwaves, heart rate, breathing and blood pressure.

“It’s like a biopsy of your sleep,” says Dr. Rami Khayat, a professor of clinical medicine who directs the program. Surprisingly, despite the tangle of wires and electrodes attached to patients’ foreheads, chins, chests and limbs, “people sleep pretty well here,” he says. “We rarely get a study that’s unusable.”

The sleep center, which is billed as the only academic comprehensive clinic of its kind in Orange County, also conducts alertness tests for pilots, military personnel, truck drivers, physicians and others whose jobs depend on staying awake.

Not everyone with a 40-winks problem needs to stay overnight at the lab.

In cases where sleep center doctors suspect only obstructive apnea – a condition that affects nearly 30 percent of U.S. adults and about half of the clinic’s patients — a home monitoring kit analyzes the person’s shut-eye. Similarly, insomniacs get medical-grade smartwatches that track their vital signs and — unlike consumer wrist gadgets — are backed by peer-reviewed scientific studies, Khayat says.

The resulting data can run hundreds of pages and is manually scrutinized to recommend the best treatment.

More than half of Americans suffer from some sort of sleeping disorder, although they may not realize it, Khayat says. Left untreated, sleep dysfunction increases the risk of heart attack, stroke, diabetes, dementia and cancer, he adds, not to mention impaired decision-making and driving.

What are the warning signs?

“How do you usually feel when you get up in the morning?” Khayat asks. “If you’re not refreshed, it may indicate a problem. Or if you often get really tired later on, that’s not normal.”

At any age, people should have some energy left in the tank at the end of the day, he says.

For new patients, clinic doctors spend about an hour discussing the person’s sleep environment and routines, checking their airways, reviewing medical records and outlining options. Overnight tests — either at home or in the lab — are recommended more than half the time, Khayat says.

The center, which opened in 2018, uses state-of-the-art equipment, including technology devised by UC Irvine inventors. One wireless UC Irvine creation worn like a sock unobtrusively monitors blood pressure and can even predict which apnea patients are more likely to develop heart problems, Khayat says.

Once a diagnosis is made, treatments range from behavior modifications (“Some problems are self-induced,” Khayat notes) to breathing masks or surgically implantable devices. Medications are occasionally prescribed, usually for such conditions as narcolepsy, severe insomnia or excessive drowsiness. But the clinic prefers to avoid pills and offers one of the few behavioral sleep programs in the county.

For patients with central sleep apnea, a rarer form of apnea, UC Irvine is the only Orange County health system to offer Remede, an FDA-approved nerve stimulator that works sort of like a pacemaker, Khayat says.

Along with treating everything from drowsy driving to excessive nightmares, the center hosts various UC Irvine research projects, including studies on the relationship of slumber to dementia and heart disease. Some of the test subjects wear what looks like a swim cap covered with dozens of metal buttons. It’s actually a high-density EEG headpiece that can draw a 3D map of brain activity and predict cognitive impairment.

Looking to the future, Khayat hopes to expand the clinic’s staff and launch a sleep medicine training program at UC Irvine. “As a society, we’re sleeping less, and disorders are increasing,” he says, so the demand for care is growing. But with few area universities teaching the field, “There’s a shortage of sleep physicians.”