Krissy Eliot, California Magazine

Passwords and humans are frenemies: We tolerate each other because we have to, but we seem to know that one will screw the other over sooner or later (as evidenced by the many security breaches of 2015). Managing our password portfolio is more maddening than ever, given that more than half of us have five or more unique passwords, and nearly a third of us have more than 10.

Little wonder a 2012 study revealed that 38 percent of us say we would rather scrub a toilet than create and remember yet another username or password.

In a desperate attempt to extricate the often-insecure numeric- and letter-based passwords from our lives, some have embraced biometrics. Apple added fingerprint authentication to the iPhone 6, Samsung deployed a facial recognition feature on its Galaxy smartphone, and Nuance began using voice alone for identification. But already these biometrics have proved themselves vulnerable, with hackers copying fingerprints and bypassing facial recognition by holding victims’ photos in front of the devices. And researchers warn that voice imitation is easy to master, especially because we frequently speak out loud in public.

Nonetheless, specialists are racing to improve these avant-garde technologies. As a result, market researchers predict that biometrics will soon be the new black, with half of us accessing mobile devices biometrically by 2020.

But do such predictions really mean much?

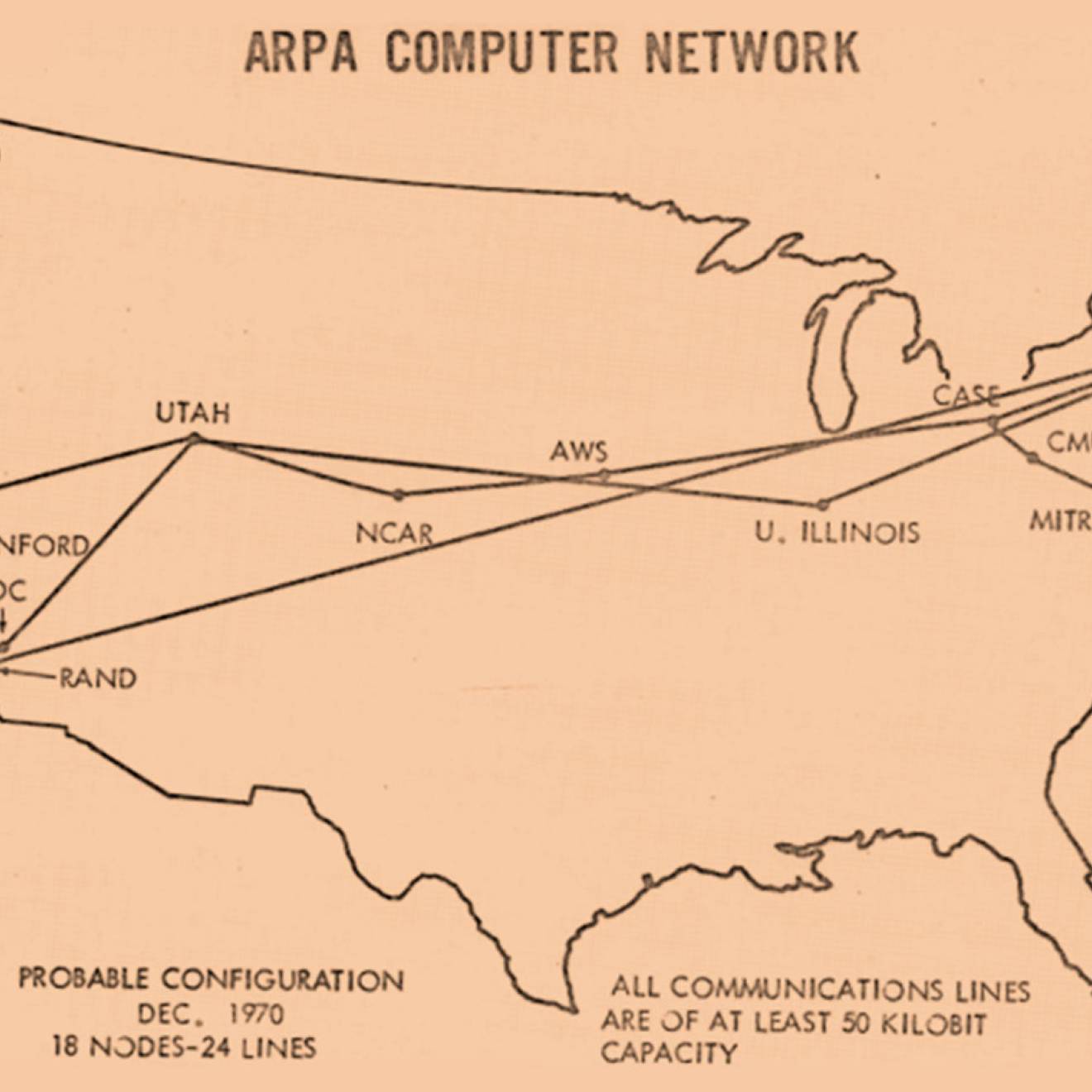

“So some people think biometrics are going to be widespread soon. Forgive me if I’m a little cynical, but I’ve been hearing this since the 1970s, and I’m still waiting,” said James Wayman, who invented biometric authentication based on acoustic resonance in the human head, a project he carried out for the U.S. Defense Department. Currently he is honorary professor of biometrics at the University of Kent in Canterbury, England.

Wayman cited studies from the 1970s, in which researchers forecasted that fingerprints would largely displace passwords by 1980, and voice and facial-feature recognition would be commonplace everywhere by 1985. Clearly, that didn’t happen — and the technology has been around for quite a while now.

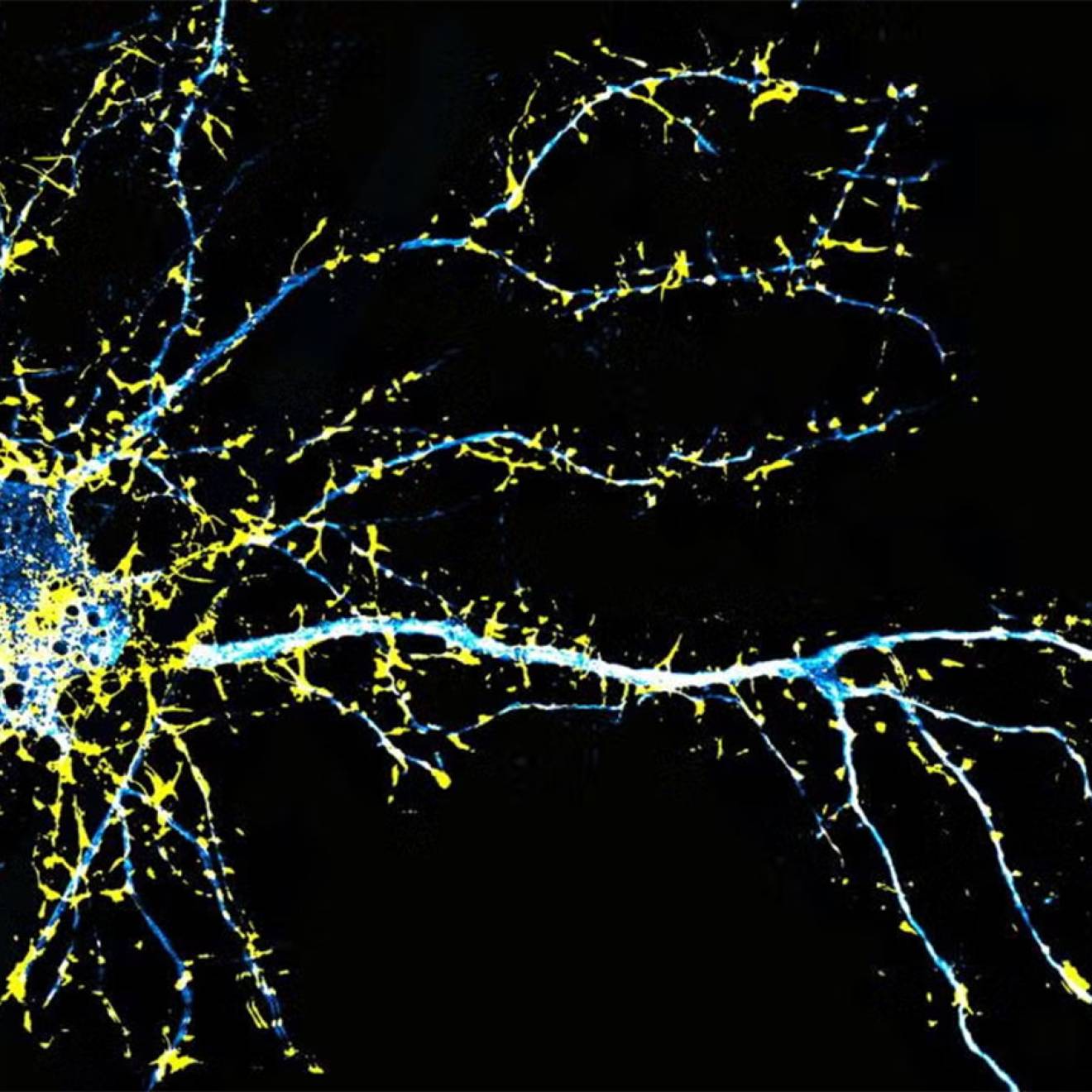

For biometrics to truly dislodge passwords, a different approach is necessary to make them more secure. UC Berkeley School of Information professor John Chuang thinks a solution to this problem may lie in one-stop-shop biometrics — that is, multi-factor authentication achievable with one biometric passcode.