Jim Logan, UC Santa Barbara

The woman’s voice is faint, low and barely audible as she identifies herself: R.C. Wombough. Such a statement would seem wholly unremarkable if not for the fact that R.C. — Rachel Cornelia — was born 200 years ago.

Captured in an audio recording in 1898, Wombough’s voice is among those immortalized in the Vernacular Wax Cylinder Recordings at the UC Santa Barbara Library. The collection includes nearly 700 recordings from the early 1890s through the 1920s. Deeming it “culturally, historically or aesthetically important,” the Library of Congress has added UCSB’s collection to its National Recording Registry.

“The UCSB Library is dedicated to preserving and making accessible the unique materials in our Special Research Collections,” said University Librarian Denise Stephens. “Digitizing these rare early recordings preserves the voices of America for future generations, and we are grateful to the Library of Congress for enabling even more people to learn about our collective history through these resources.”

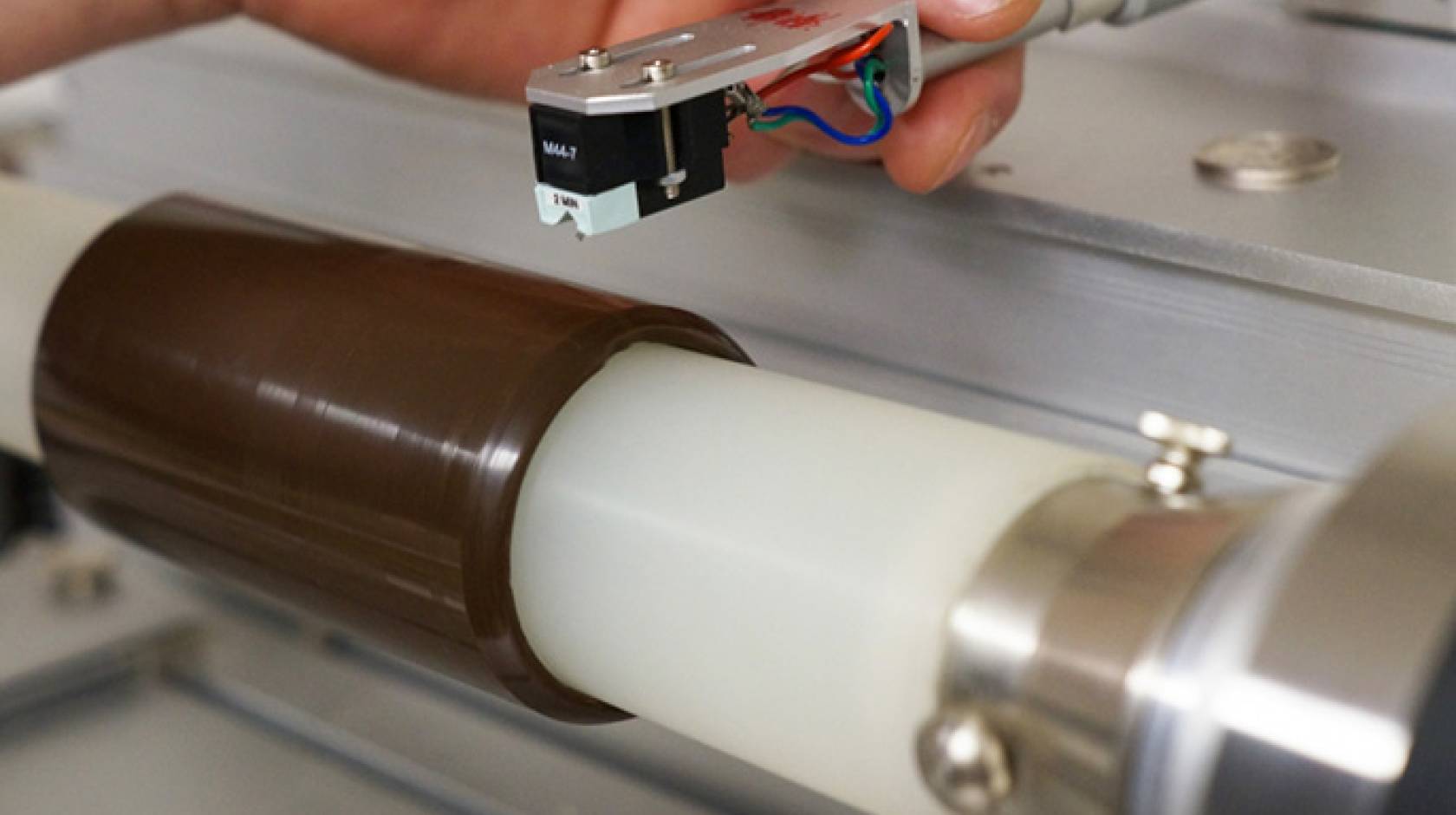

David Seubert holds an Edison Records concert cylinder.

Credit: Sonia Fernandez

According to David Seubert, director of the UCSB Library’s Department of Special Research Collections, inclusion in the registry is a testament to the special nature of the recordings. “It’s an acknowledgment that this particular type of recording is essentially unique,” he said, “and this genre is an important cultural artifact that should be recognized and preserved.”

UCSB’s collection of vernacular wax recordings consists largely of what might be described as audio selfies of the day — the quotidian sounds of life, including jokes, songs, music and the cries of newborn babies and animals. More than 500 make up the David Giovannoni Collection of Home Cylinder Recordings, which were collected over four decades by Giovannoni, a sound historian, and Donald R. Hill, a professor of anthropology at State University of New York at Oneonta. UCSB acquired the collection from Giovannoni in 2013.

Every year since 2002 the National Recording Preservation Board (NRPB) and members of the public have nominated recordings to the registry, and 25 or so are selected each year. Recordings can be a single item or group of related items, published or unpublished, and can contain music, non-music, spoken word or broadcast sound.

The registry, which was created as part of the National Recording Preservation Act of 2000, includes Edison cylinders, field recordings, radio broadcasts, rap albums, live concerts, poetry readings and more. Among the 400 recordings already in the registry are Martin Luther King’s 1965 “I Have a Dream” speech, the first transatlantic radio broadcast from 1925, and Igor Stravinsky conducting his “Rite of Spring” in 1940. The Library of Congress does not have copies of all the recordings; many are housed in collections around the country.

“They’re basically landmarks of American culture,” Seubert said. The UCSB Library has a collection of more than 650 vernacular wax recordings, also known as home wax recordings. In addition to the Giovannoni holdings, the library has roughly 150 other home recordings that will be part of the registry as well. These were produced by everyday people, not record companies or field researchers, and capture the early spirit of the public’s interaction with recording technology.

From its commercial introduction in the 1890s through its demise in the 1920s, the cylinder phonograph allowed its owners to make sound recordings at home. Their audio “snapshots” of everyday life are perhaps the most authentic audio documents of the period: unfiltered encounters with ancestors unburdened by commercial or scholarly expectations. They are among the most endearing recordings of the period: songs sung by children, parents and other relatives; instrumental selections, jokes and ad-libbed narratives; and even the cries of newborn babies and barnyard animals.

The collection also contains larger groupings of cylinders created by the same people and discovered together years later, providing in-depth coverage of the lives of individual families and communities, such as recordings made by William Henry Greenhow, who recorded his mother, R.C. Wombough. Born in 1823, she is the earliest-born American woman whose voice is known to survive on record.

Among other holdings in the collection are the oldest known recordings of American vernacular fiddle music, from as early as 1900; speeches commemorating Jan. 1, 1900; singing by a Civil War veteran; and a sales pitch for the Vikings’ Remedy, a wholesome medicine that “cures when doctors fail.”

Wax recordings are among the most endangered of all audio formats: Their grooves are extremely fragile and shallow; the wax on which they are recorded decomposes with time; archives find them challenging to catalog; and collectors shave off their recordings to make new ones.