Coby McDonald, California magazine, UC Berkeley

In late January of 1958, five of America’s most renowned writers converged in a repurposed frat house just off the Berkeley campus for what promised to be a long, strange weekend. Formerly the Sigma Phi Epsilon house, the mock-Tudor structure was now the headquarters and laboratory of Berkeley’s Institute of Personality Assessment and Research, or IPAR. In a nod to the observational studies that took place inside, the institute’s founding director, psychologist Donald MacKinnon, called the building “the fishbowl.” And for three days, this small group of writers — among them a young Truman Capote — would be the goldfish, subjects of an unprecedented study into the secret sauce of creativity.

When MacKinnon created IPAR in 1949, he was already one of the world’s leading assessors of human aptitude. He had sharpened his talents during World War II as the director of Station S in Fairfax, Virginia, for the Office of Strategic Services (precursor to the CIA). There MacKinnon screened candidates for jobs in irregular warfare — as spies, counterespionage agents, leaders of resistance groups. The elaborate battery of psychological tests honed at Station S became known as “the assessment method,” and after the war, MacKinnon wondered how else it could be put to productive use. Then Berkeley called.

Initially the admissions office tasked MacKinnon with creating better assessments for selecting graduate students. But soon, with funding from the Carnegie Corporation, IPAR’s mission expanded to unlocking the secrets of personality.

“MacKinnon brought that same [OSS] methodology to IPAR,” says William Todd Schultz, professor of psychology at Pacific University, who is working on a book about the IPAR writers studies. “It was very ambitious.”

At Berkeley, the former spy screener assembled a group of eclectic, high-powered psychologists to join him. Early IPAR research focused on the concept of the “effective person.” They wanted to know both the ingredients of the successful personality and the societal conditions that allowed such people to thrive — the nature and nurture of success.

But in the mid-1950s, an obsession with creativity took hold in America. Not the watercolor and pottery kind, but rather creative thinking as a means to solve the world’s most pressing problems. As author Pierluigi Serraino noted in his 2016 book, The Creative Architect: Inside the Great Midcentury Personality Study, the project was considered to be of existential importance: “As alarming visions of an Orwellian society dominated by automated technologies were going viral in postwar Western civilization, the investigation on creativity was seen as a crucial tool in the race for humanity’s very survival, saving it from an obliteration of its own making.…”

As it happened, IPAR had a creativity expert on staff. Psychologist Frank Barron was known for blending ideas from philosophy, religion, and the arts into his personality research. He and MacKinnon had an idea: If they could bring America’s most formidable writers (and architects, mathematicians, etc.) to the fishbowl for a few days and use MacKinnon’s assessment tools on them, the secrets of creativity might just be revealed.

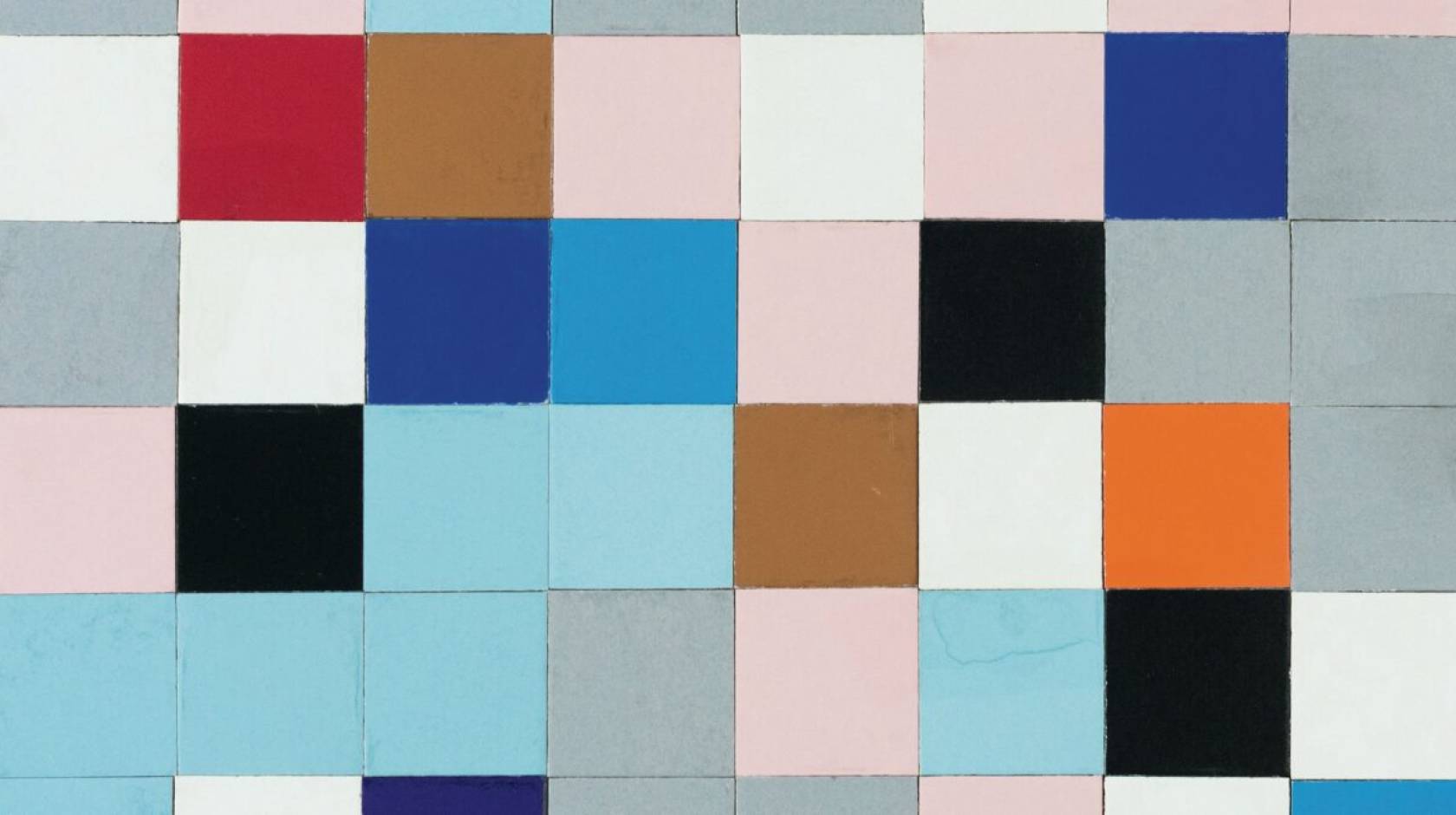

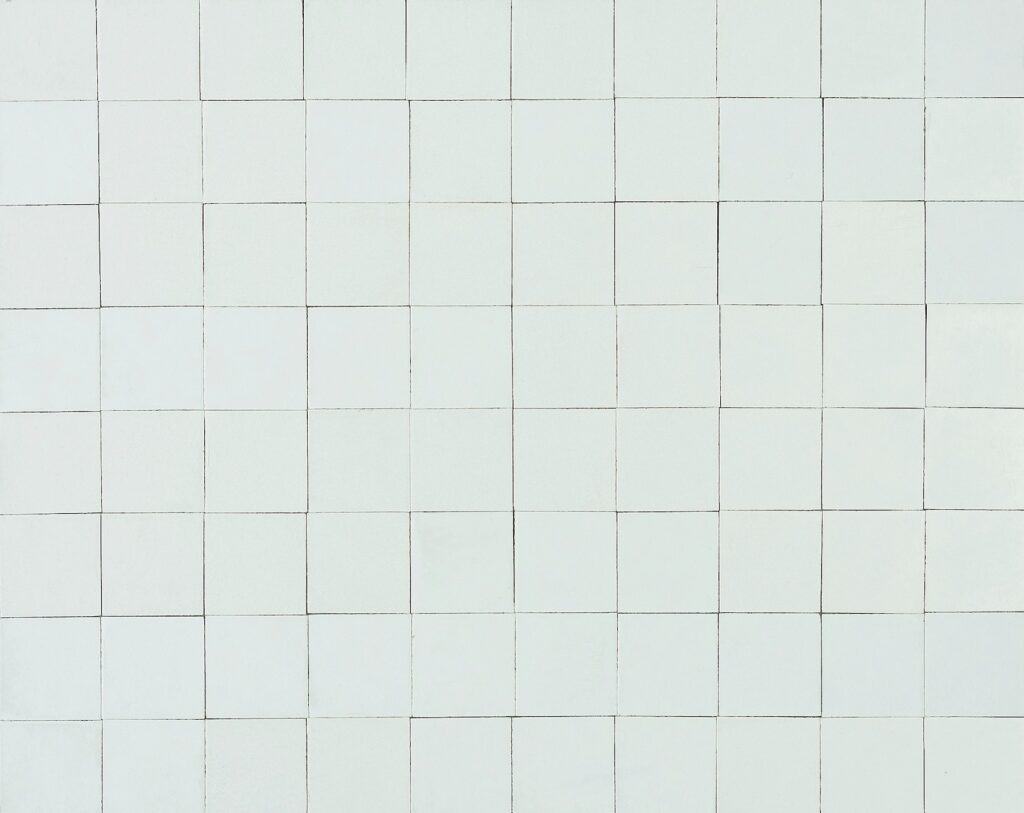

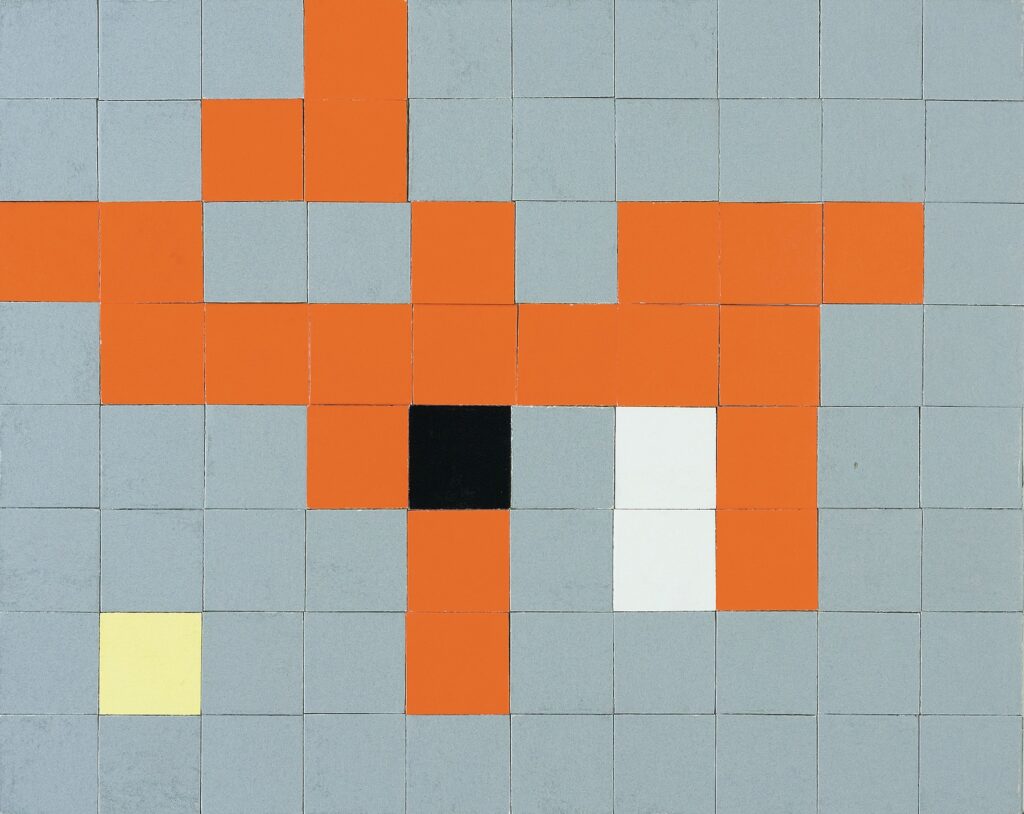

From the moment Capote and his fellow writers entered the IPAR house that winter morning, they were under careful observation by note-taking graduate students. The group, which included novelists, a poet, and a literary critic, was subjected to numerous assessments, some familiar, like Myers-Briggs and Rorschach tests, and others not so much. One required them to arrange colored tiles into a mosaic. Another tasked them with choosing their favorite pattern from a series of Scottish tartans. Group activities had them discuss contingency plans for the end of the world and collaborate on story plots. There was even a test using a Ouija board to measure the writers’ suggestibility.

“One of the distinctive things about IPAR is they believed that personality was a complicated whole,” says Schultz. “And to really get a sense of a person you need to come at that person from multiple angles.”

The subjects were often skeptical. One of Barron’s subjects, Kenneth Rexroth, known as the “godfather of the beat poets,” later described his IPAR experience in a long, caustic prose poem entitled “My Head Gets Tooken Apart.”

“I sorted things and interpreted symbols. A rather frightened, puzzled, but very determined looking young woman took me in the attic, blindfolded me, led me into a dark room, and spent twenty minutes finding out if I could tell vertical from horizontal. Honest to God, cross my heart, hope to die. I could, pretty good.”

At times the subjects were given breaks to drink and socialize, but these cocktail hours were actually assessments in disguise. Utilizing what MacKinnon called the “house party” approach, assessors took careful note of their behavior and interactions.

“It’s kind of a cool, unusual thing that’s unimaginable today,” says Schultz. “One thing about that group of researchers was that there were no limits. They were extremely broad-minded. They were going to try anything.” In other words, they were getting creative.

And perhaps they needed to, given the elusive nature of their subject. Creativity is a nebulous concept, variously defined, and difficult if not impossible to measure. The field of creativity research, MacKinnon felt, had long been awash in untested theories and what he called “armchair model-building.” He was determined that with empirical studies he could wrestle the concept to the ground once and for all.

While Rexroth was clearly unimpressed, Capote was an enthusiastic and forthcoming participant. He provided researchers plenty of raw material, holding forth about his famous friends, difficult childhood, nightmares, and more. And the three days at IPAR may have been productive for Capote too. According to Merve Emre, author of The Personality Brokers, during one collaborative assessment, Capote workshopped an early version of Holly Golightly, the future protagonist of Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

Barron would ultimately bring 31 prominent writers to IPAR for assessment, among them Norman Mailer, Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist MacKinlay Kantor, and poet William Carlos Williams. (Two years later, Barron would co-found the infamous Harvard Psilocybin Project along with a former IPAR graduate student, Timothy Leary.)

And it wasn’t just writers who were put in the fishbowl. Creativity studies were also conducted on mathematicians, research scientists, and architects. The latter was practically a Who’s Who of mid-century modern masters. Eero Saarinen, Richard Neutra, George Nelson, I.M. Pei, they were all there. (IPAR study subjects were overwhelmingly white and male, a longitudinal study of Mills College graduates being a notable exception.)

The influence of the IPAR studies is lasting, the work still cited in both scientific and popular literature. Monty Python comic John Cleese drew two salient conclusions from the architect study in his 2020 book, Creativity: A Short and Cheerful Guide. One was that the most creative architects know how to play. The other one, perhaps less intuitive, was that they deferred important creative decisions to the last moment. They weren’t procrastinating so much as giving their minds more time to work on the problem.

Among the other conclusions, IPAR researchers noted that creatives tended to have a good opinion of themselves; they were also risk-takers, on the whole, who thrived on ambiguity and complexity and had a high tolerance for chaos; and they often scored high on traits that in 1950s America were widely viewed as feminine, including self-awareness and an openness to their feelings. Notably, the studies revealed that “above a certain required minimum level of intelligence” there was no correlation between creativity and intelligence. MacKinnon wrote that, in some creative individuals, IQ was “surprisingly low.”

There were also contradictions aplenty. Barron himself commented that the creatives were “both more primitive and more cultivated, more destructive, a lot madder and a lot saner than the average person.” Not exactly a consistent profile. And not everyone in the field was sold.

“The research was a little bit what we call in science ‘underpowered,’” says former director of the institute, Professor Emeritus Robert Levenson. The sample sizes were small, “and a lot of the measures were not replicable, in the sense that if you gave a person the same test on a different day, they might perform in a different way.”

The research continues, albeit with a different focus. In 1992, the Institute of Personality Assessment and Research received a new name: the Institute of Personality and Social Research. It was a change that reflected shifts in both American society and the field of psychology. Gone was the obsession with individual genius.

“One of the core ideologies behind a focus on identifying the exceptional person is individualism,” says IPSR’s new director (as of July), Professor of Psychology Iris Mauss. “And that’s much more aligned with the ‘P’ in IPSR.” The “S,” she says, “was added to reflect that you can only understand the human mind by looking at the social aspects of people’s psychology.”

Today’s IPSR is focused more on health and well-being for everyone, she says. Personality still has a role to play however. “We aren’t all the same, right? People differ, including in how they respond to the social conditions they live in, and how they respond to their communities,” Mauss says. “And so to understand who will thrive and who will not do so well, we absolutely need to understand personality differences, as well as social context. We need both.”

The fish and the fishbowl.

Coby McDonald is a frequent contributor to California and producer of The Edge, the magazine’s podcast. He last wrote in this space about the staying power of Telegraph Avenue’s iconic record shops.