Kathleen Maclay, UC Berkeley

UC Berkeley, economist and assistant professor of public policy Solomon Hsiang led the econometrics team that helped assemble a major report released Tuesday that projects significant economic risks from climate change in the United States.

The first data-driven national study to provide local estimates for economic risks to key economic sectors found that:

- The hardest-hit areas will include heavily-used and increasingly expensive energy sources.

- Labor productivity will also be hard hit as workers are sapped by the heat.

- Infrastructure damage from rising sea levels will surge when combined with hurricane storms.

- There is a roughly 50 percent chance that by conducting business-as-usual in terms of climate action, the nation’s climate-related mortality rates will rise to 1 to 3 times that of the motor vehicle mortality rate.

'Hard-nosed risk analysis'

While some findings sound sensational, the report itself is careful to present a balanced picture, said Hsiang, who called it “a hard-nosed risk analysis, produced as if the U.S. were run like a firm.”

“We’re not forecasting the collapse of the United States economy or civilization,” he said. “Some populations even benefit. But overall, the impacts of climate change are substantial, with clear risks.”

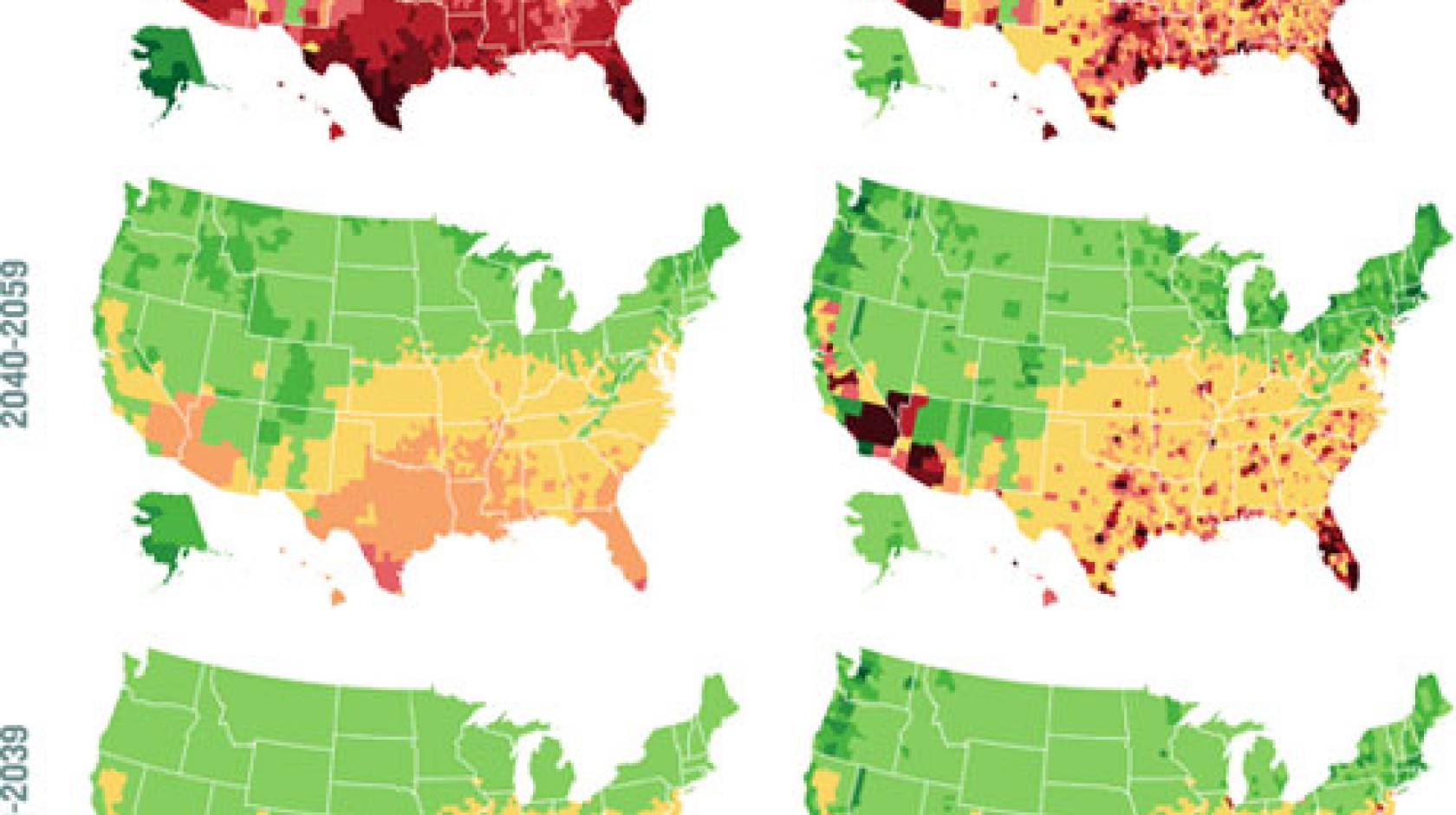

The report is the first to evaluate economic impacts in multiple sectors down to the county level, allowing decision-makers to understand how different regions will be affected by climate change.

Overall, the researchers found that states in the South, Midwest and Great Plains bear the largest economic burden from climate change, while a handful of states, like Oregon and Washington, are likely to benefit economically from climate change.

Previous reports tended to blur these different effects across the country, reporting only national average impacts that make the economics of climate seem rosier than they actually are, said Hsiang. For example, he noted that the report estimates that there is a 2-in-3 chance that by the end of the century, Florida will suffer annual losses worth roughly 10-23 percent of the state’s entire Gross Domestic Product.

Climate change and income inequality

“If you average over the entire country,” Hsiang explained, “you get a picture that is backward, because damages sound smaller. But we know from observing people’s normal behavior as well as lab experiments that they dislike inequality,” which means they are actually willing to spend resources to avoid exacerbating economic inequalities. The report finds that national patterns of income inequality are reinforced by climate change, because poor states tend to be more impacted than rich states.

The findings of the “American Climate Prospectus: Economics Risks in the United States” are summarized in a policy document issued today by the Risky Business initiative, established to explore the issue and led by former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, former hedge-fund manager Tom Steyer and former U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulsen.

Hsiang previewed some of the report’s scientific innovations in April during his keynote lecture at the nation’s largest meeting of climate-related insurers and reinsurers in Washington, D.C., but none of the study’s findings were made public until today.

The report is considered to be comparable to the “Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change,” a game-changing, 700-page analysis that was produced in 2006 for the British government by economist Lord Nicholas Stern, a distinguished professor at the London School of Economics. Stern called for early and strong action to deal with climate change. Stern’s report was largely theoretical, in sharp contrast to the data-heavy American Climate Prospectus released today.

The latest study was co-led by Hsiang, Rutgers University professor and climate scientist Robert Kopp and Trevor Houser of the Rhodium Group, a private research firm. Working on the econometrics team with Hsiang were Columbia University doctoral candidates Amir Jina and James Rising. Jina was a visiting researcher at the Richard and Rhoda Goldman School of Public Policy at UC Berkeley while working on the project.

Focusing resources

Hsiang said he hopes the study will help Americans understand the economic consequences of climate change at a local level, spur rational dialogue about the concrete impacts of climate change and help policymakers make more informed decisions about the many facets of climate change policy.

“By seeing where economic impacts are big or small helps us focus our business and public policy resources efficiently,” said Jina.

The study drew from the decades of climate research, then integrated that work with the latest econometric analyses to develop empirical, data-driven results. Rising explained that improvements in computational power and other methodological advances made it possible to deal with the terrabytes of data he used in the analysis, something that would have been impossible just a few years ago.

“Our actions today are shaping our nation’s economic future,” said Hsiang, “This analysis is like a flashlight at night: it lets us see what’s up ahead.”