Iqbal Pittalwala, UC Riverside

Cancer researchers and drug companies may have been too quick to ignore a promising line of inquiry that targets a specific cell protein, according to a research team led by a biomedical scientist in the School of Medicine at the University of California, Riverside.

Every cell in our body produces pro-death proteins and anti-death proteins, which interact with each other, negating each other’s function. A healthy balance between them is a natural process. A damaged cell, for example, produces more pro-death proteins than anti-death proteins, resulting in a natural elimination of the diseased cell, a process also known as apoptosis. Pro- and anti-death proteins are therefore termed pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins, respectively.

In cancer cells, genetic alterations result in an overproduction of anti-apoptotic proteins. As a result, such cancer cells keep surviving and become resistant to treatment (chemotherapy or radiation) instead of dying, resulting in uncontrolled proliferation.

Anti-apoptotic proteins, therefore, have been the target for developing drugs that restore apoptosis in cancer cells. Bcl-2 is a member of a family of six anti-apoptotic proteins. It is the most studied of the six proteins, and the drug Venetoclax, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2016, targets it.

But what if cancer cells develop resistance to this drug, which targets only one anti-death protein? Based on studies using mouse proteins, academics and pharmaceutical companies have been focusing on the next anti-apoptotic protein in the line-up: Mcl-1.

A unique case among human proteins

When cancer cells are exposed to chemotherapy, radiation or even immuno-therapy, pro-apoptotic signals, such as the toxin NOXA, are produced in the cell that result in cancer cell death. Two anti-apoptotic proteins, Mcl-1 and Bfl-1, are known to oppose the effects of NOXA. Hence, inhibitors of these two anti-apoptotic proteins may complement Venetoclax in restoring apoptosis in cancer cells. Most efforts have been concentrated only on Mcl-1, because studies with mouse proteins have shown that NOXA interacts very tightly with Mcl-1 and sequesters it.

But a team of researchers led by Maurizio Pellecchia at UC Riverside cautions that the focus needs to be on a different anti-apoptotic protein: Bfl-1.

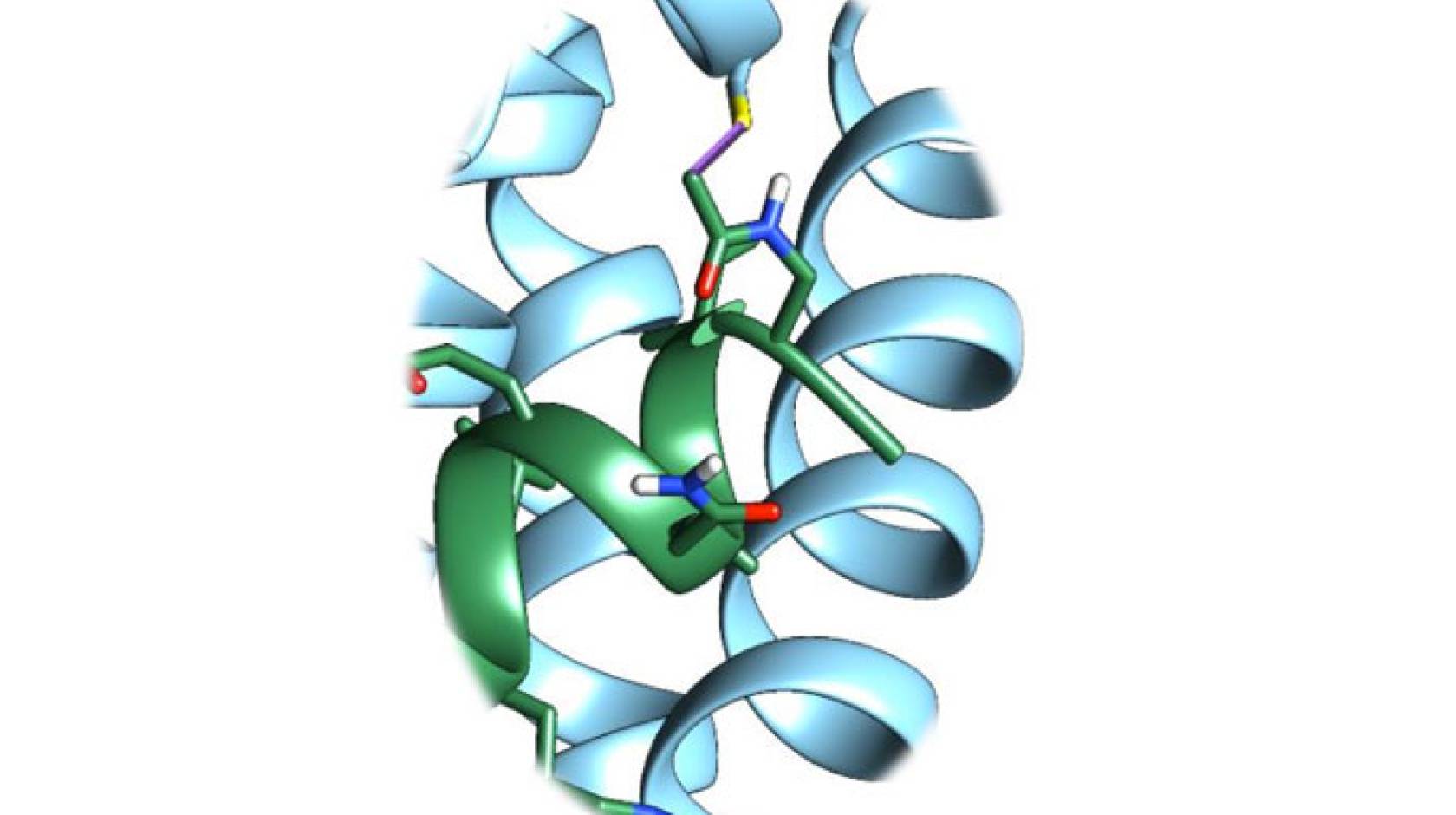

Credit: UC Riverside School of Medicine

“What we discovered is that while these early studies done with the mouse versions of the proteins NOXA, Mcl-1, and Bfl-1 were correct, these do not entirely apply to human proteins,” said Pellecchia, a professor of biomedical sciences and the Daniel Hays Endowed Chair in Cancer Research. “This is because human NOXA and Bfl-1 are different from their mouse counterparts. Indeed, we found that when we profiled human NOXA against human anti-apoptotic proteins, the highest affinity was for Bfl-1, and not for Mcl-1, making Bfl-1 a much more relevant drug target than previously assumed.”

Study results appear in ACS Chemical Biology.

Pellecchia’s lab found that NOXA interacts with Bfl-1 through a unique chemical bond (a “disulfide bridge” between unique sulfur atoms present on each protein) not seen in the other five anti-apoptotic proteins.

“Understanding how NOXA interacts with Bfl-1 allowed us to devise in the lab a surrogate NOXA-like molecule that very tightly and permanently binds and inhibits Bfl-1,” Pellecchia said. “In proof-of-concept studies with cells from patients affected by chronic lymphocytic leukemia that are resistant to chemotherapy, we showed that if we block Bfl-1 with this innovative inhibitor, the cells begin to die in response to treatment.”

Promising drug target

The research advocates strongly for focusing on Bfl-1 as a drug target.

“Academics and pharmaceutical companies are spending considerable amount of effort and resources in finding antagonists to Mcl-1,” Pellecchia said. “While these agents are surely useful in certain conditions that are exacerbated by over-production of Mcl-1, we have shown that more focus on Bfl-1 is warranted. Our research provides new insights on the mechanisms of cancer resistance to chemotherapy, suggesting Bfl-1 as a viable drug target, and also provides a direct path on how to develop Bfl-1-targeting drugs.”

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Research Consortium, the UC San Diego Foundation Blood Cancer Research Fund and the Bennett Family Foundation.

Pellecchia was joined in the research by Elisa Barile (first author of the research paper), Guya D. Marconi, Surya K. De, Carlo Baggio, Luca Gambini, and Ahmed F. Salem at UCR; and Manoj K. Kashyap, Januario E. Castro, and Thomas J. Kipps at UC San Diego. Baggio and Gambini are postdoctoral scholars in Pellecchia’s lab; De and Salem are project scientists in his lab; Barile and Marconi are currently at UC San Diego.