Wallace Ravven, UC Newsroom

Nobody looks forward to the April 15 tax-filing deadline, but it's not all gloom. Every year, thousands of Californians brighten the outlook for cancer prevention and treatment by using tax time to make a donation to research and community-based education.

Donations help support a wide range of programs, from leading-edge research aimed at early detection of lung cancer to exploring with teens the toxins found in everyday beauty products.

Taxpayers can support research and community education through the California Breast Cancer Research Program (CBCRP) with a check-off on line 405 of California Tax Form 540. Line 413 furthers projects funded by the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (TRDRP), which focuses on cancer and other diseases caused by tobacco products.

The University of California administers both programs, and puts a priority on projects aimed at communities that are disproportionately at risk for cancer.

Reducing breast cancer risk among young Latinas

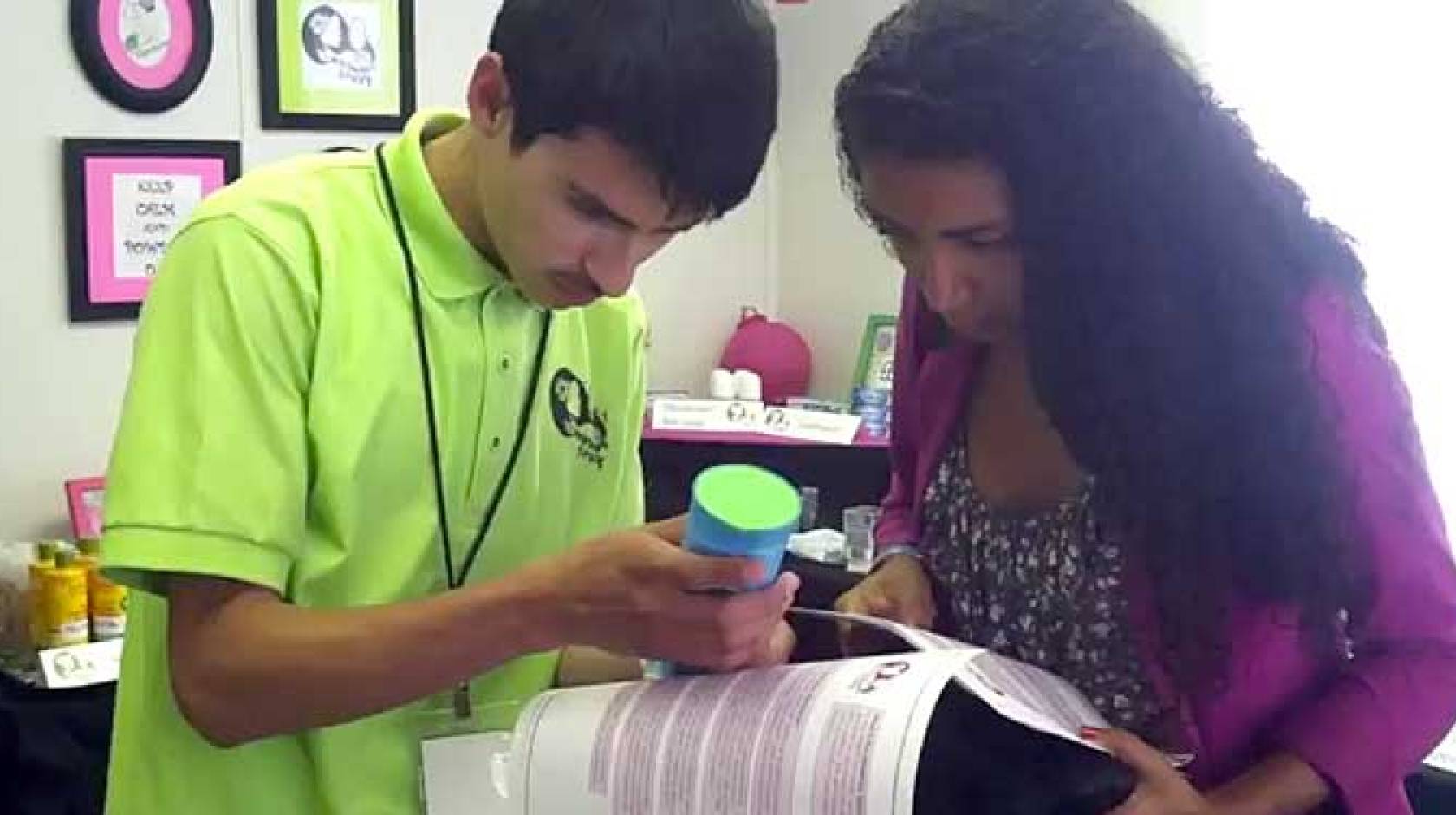

An innovative community health partnership in East Salinas, for example, teaches young Latinas about the potential breast cancer risk posed by the chemicals that are found in some cosmetics, shampoos and other personal care products.

Funded by the CBCRP, the project has brought together UC Berkeley public health professor Kim Harley with Kimberly Parra at the Clinica de Salud del Valle de Salinas to carry out cancer-risk research and offer health education and practical training to teens.

Harley focuses her work on chemicals that can act as endocrine disrupters, meaning they mimic or block the normal effects of hormones such as estrogen. Endocrine disrupters are suspected of being a key factor in the development of breast cancer.

Young girls and minority women tend to have higher levels of the chemicals in their blood than non-Hispanic whites.

Sixteen local youths have been trained to design and carry out research to determine what products local teens use, the amount of endocrine disrupters they are exposed to in these products, and whether switching to low-chemical alternatives will decrease their exposure.

“Working with teens in this community has been really rewarding,” Harley says. “We have watched them learn that science can be accessible and fun, and relevant to their lives.

"At the same time, we have learned from them about what environmental health issues are important to them. It has really helped us conduct effective, appropriate research that can affect change among youth.”

The prevention message is spreading beyond the teens involved: Two local TV news stations — one English-language, the other Spanish-language — have reported on the project. And both the teen researchers and their subjects are sharing what they learn about endocrine disrupters with friends and family.

Targeting cancer in the brain

Prevention holds the greatest promise for reducing cancer illness and death, but treatment forms the crucial second line of defense.

When breast cancer cells spread to the brain, the disease becomes particularly difficult to treat. The body’s natural physiological buffer, known as the blood-brain barrier, prevents bacteria and other blood-borne invaders from entering the brain, but also closes the door to chemotherapy targeting the brain.

At the University of Southern California, Axel Schönthal is applying CBCRP tax check-off funds to developing a novel strategy that would allow chemotherapy drugs to reach the brain through inhalation.

The drug, commonly known as temozolomide, has been proven effective against particularly aggressive brain tumors, but it must be given orally and can cause severe side effects throughout the body.

Schönthal predicts that inhalation of the drug will increase effectiveness in destroying cancer cells in the brain while reducing side effects. He expects that the intranasal treatment can work well against many types of breast cancer that have metastasized to the brain, particularly cancers that have proved resistant to most other drugs.

Such difficult-to-treat cases, called triple-negative breast cancer, are particularly prevalent in African-American women.

As federal NIH budget cuts have increased, Schönthal says, the tax check-off contributions for CBCRP-funded projects have become a lifeline for research aimed at treating and curing a range of cancers.

He especially values the fact that patient advocates are often part of the team that evaluates CBCRP research proposals.

“It is important that funding focuses on research of importance to affected communities,” Schönthal says.

Early detection of cancer's leading killer

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in both men and women in the U.S., and smoking accounts for more than 80 percent of lung cancer cases. Many smokers contract a less familiar but debilitating disorder called chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD, before they are diagnosed with lung cancer.

Lung cancer and COPD don’t strike all smokers, and genetics almost certainly influences disease vulnerability.

Identifying the genetic underpinnings common to both lung cancer and COPD vulnerability may reveal the biological processes that are triggered by smoking — creating new avenues for early warnings and novel interventions.

Cancer epidemiologist Lori Sakoda at the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research has launched a study supported by TRDRP to search for genetic traits shared by people with either or both diseases.

Although resisting smoking or breaking the habit are the surest way to prevent cancer and COPD, “once lung cancer develops, it is potentially curable if it is caught before it metastasizes, so early diagnosis is crucial,” Sakoda says.

Low-dose CT scans have become an accepted early detection strategy, but like any screening test, it carries risks. Sakoda’s research seeks to identify genetic markers that might help clinicians zero in on which subgroup of chronic smokers is at highest risk for either or both diseases, and so, pinpoint them as strong candidates for CT screening.

The study focuses on former or current smokers from a large, ethnically diverse cohort of Kaiser Permanente Northern California members.

Lowering the dose

Credit: Elena Zhukova

A second TRDRP-funded study aims to determine the lowest possible CT dose that can reliably detect small nodules that mark the early stages of lung cancer.

“We want to find just how far we can ‘dial down’ CT dose without losing critical sensitivity," says UCLA’s Michael McNitt-Gray. Drawing on CT scans of patients that already show telltale cancer nodules, his team applies imaging software to simulate the clarity that would be provided by scanning with lower CT exposures.

“It’s like trying to see how low you can turn down the light in a room and still clearly see,” he says.

McNitt-Gray hopes the exposure can be reduced significantly beyond currently accepted methods for screening CT exams — “possibly by as much as 50 to 75 percent without sacrificing our ability to detect those small nodules.”

“Detecting lung cancer in its earliest stages can save lives,” says Bart Aoki, Ph.D., director of the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program. “We are very pleased to be able to support projects that foster awareness in underserved communities as well as research by the outstanding scientific community in California."

Both the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program and California Breast Cancer Research Program receive financial support from a California tax on tobacco products. As smoking rates decline, so too, does their funding for these important projects.

“Reduced smoking is of course great news for improving public health, but it threatens our ability to fund significant research,” says Marion Kavanaugh-Lynch, M.D., MPH, director of the California Breast Cancer Program. “We depend on California taxpayers to help offset this decline by voluntary contributions on their tax returns."