If you live in an urban area, you may’ve noticed your sidewalk is a little busier than usual. Not just as a result of downtown revitalization or roving millennials. New modes of transportation are literally popping up overnight.

That’s right: Scooters.

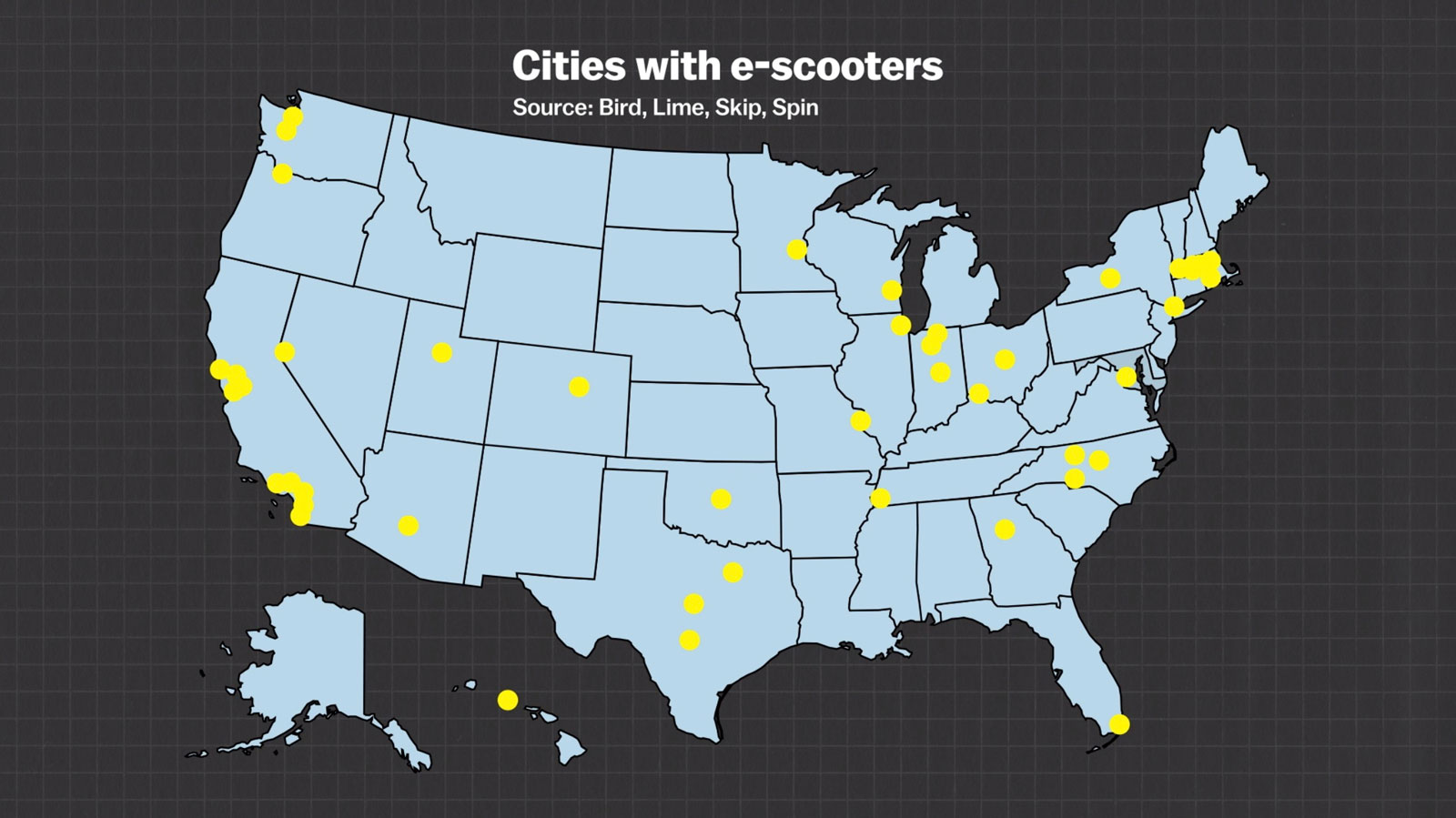

More than 80 American cities had dockless electric scooter rentals on their streets as of Aug. 2018.

Provided by companies like Lime and Bird, dockless electric scooters have begun to litter city streets. How you feel about them may depend on whether you ride them or not.

For the scooter user, the zippy machines can shorten a 20-minute walk into a 5-minute ride for just a few dollars. As a result, scooters have been used for millions of rides since they first appeared in mid-2017.

Pedestrians, meanwhile, find themselves facing new hurdles, sometimes literally: not only do they have to bob and weave to avoid collisions with the 38-lb vehicles, but riders are pretty much free to leave them wherever they please. The result is a hazardous mess, as shown below.

Investors are betting big on the future of scooters — startup Bird doubled its valuation to $2B in just four months — and it looks like scooters are here to stay, even as some cities enact moratoriums while they tackle how to best regulate them.

But are scooters the enemy? Some urban planners think they are a natural outgrowth of a deeper problem about how we get from place to place. Scooters, in fact, could be just what we need to force a bigger conversation about making our streets a better experience for everyone.

Sidewalk U.S.A.

The fight over electric scooters is really a fight over who controls the sidewalk. And the reason we’re fighting, is that there is so little space to go around.

How did American sidewalks end up so small? And so unwalkable? It wasn’t always this way.

San Francisco, circa 1906

Before cars changed the face of the country, pedestrians, cyclists, horses and yes, cars, shared a single throughway, which functioned as a dynamic public space for commerce, socializing and travel.

There were no sidewalks because people understood how to navigate, and speeds were relatively low.

But as cars got bigger, faster and more essential, the binaries that are now so familiar began to develop.

Beverly Hills, Calif., circa 1935

Sidewalk vs. street. Suburb vs. city.

Over the years, congestion and demographic changes have made our current set up unsustainable.

Traveling that last mile

Cars soared in popularity because — for a time — they seemed to solve one of our most intrinsic transit dilemmas, the difficulty of traveling “the last mile.”

That’s the phrase planners use to describe the distance between a transportation hub (the train station, let’s say) and the final destination (your front door).

It’s a riddle that’s plagued businesses and individuals for a while. There are lots of easy ways to ship goods thousands of miles, from one port to another, for example. But it’s far more difficult to figure out an equally cost-effective way to deliver those goods to a particular shop or someone’s home. That last mile can take up as much as 28 percent of total transportation costs.

Hypothetically, for the individual, cars are very good at solving this problem. Or at least, we’ve gotten used to thinking of them that way: 60 percent of trips of a mile or less are made with private vehicles.

But urban congestion has now reached a point where cars are a less viable option for everyone. Software engineer and data analyst Todd Schneider found that more than half of peak hour taxi rides in New York City would be accomplished faster if riders had opted to use the city’s bike share program, CitiBike, instead of taking a taxi. And it’s not just New York. As the country urbanizes, commuters everywhere have the same challenges. In large urban areas, getting between work and home is a struggle. Commuters have to fight for a parking spot at the train station, wait for a bus or hail a ride.

Investing in public transportation would help, but only if we can also figure out how people will reach that transit to begin with — that is, create efficient and convenient ways for people to travel that “last mile.”

Transit deserts

For a nation designed around the automobile, more people in the United States are dependent on public transit than you may think.

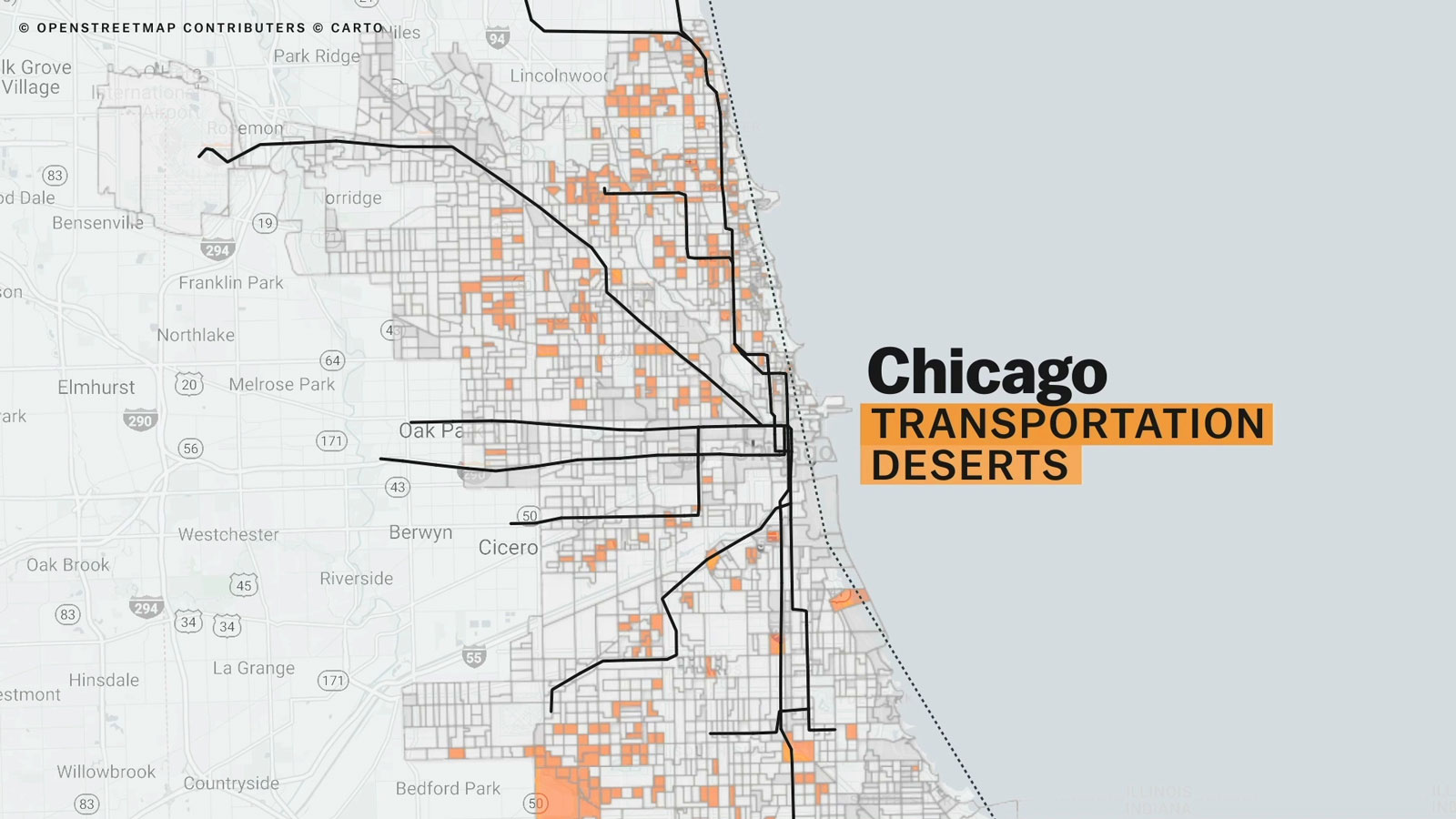

Junfeng Jiao and Chris Bischak at the University of Texas at Austin study transit in American cities, and have found that many urban areas are “transit deserts.” That is, the demand for transit far exceeds the supply.

Orange areas represent Chicago's transit deserts, places where transit supply cannot keep up with transit need.

Even where transit demand is met, a surprisingly large percentage of people are dependent on public transit — as much as 38 percent in places that aren’t transit deserts. They are too young to drive, have a disability, can’t afford a car or have otherwise decided not to own one.

In transit deserts, the number of people with unmet transportation climbs even higher: 43 percent. Not surprisingly, scooters have dropped in many of these same cities, offering a new transit option in a place where demand outstrips supply.

Meeting demand

“We’re reaching a point in cities across America, where it’s time to get people out of their cars,” says Sarah Kaufman of New York University’s Rudin Center for Transportation. “To stop providing free parking, or essentially free parking throughout cities, and allow people more modes.”

Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, a professor of urban planning at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, says that urban planners like herself have already developed a model for how that could be accomplished. It’s called “complete streets.”

A complete street with a two-way protected cycletrack in Vancouver.

It would mean a radical rethinking of the shared space that is now divided between the street and the sidewalk.

“Complete streets is a new term that entered the lexicon of planning and transportation planning relatively recently,” Loukaitou-Sideris says. “Basically it is inspired by earlier streets where you used to have all these different social uses of the streets and sidewalks — not only streets for cars, or even sidewalks for pedestrians.”

“The complete street perceives the street as a space where different transportation modes can coexist: not only cars, but also buses, and lanes for trams, bicycles and scooters.”

“But to do this you really have to sometimes redesign the street. Make space for these different modes in ways that do not conflict with one another. Nobody wants to compromise the safety of anyone by mixing these modes. So that's where planning and design needs to come in.“

The design of these new roads would likely end up looking a lot like old roads. Really old roads. And while the roads of the early 20th century may seem chaotic, the 21st century version has the potential to be way more organized, and safer. Expanding sidewalks to accommodate scooters would accommodate a number of other modes of travel and social functions, too.

So next time you see a scooter, don’t think of it as a new problem. It might just be the catalyst we need to create a much better solution, for everyone.