UC Newsroom

The Nobel Prizes were announced this week, and three of the extraordinary recipients have important connections to UC.

The Nobel Prize was established by Swedish businessman Alfred Nobel in 1895 and is designed to honor those whose work “shall have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.” First awarded in 1901, they are announced on an annual basis, and include the categories of physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, literature and peace, with economics added in Nobel’s memory in 1968 by Sweden’s central bank, Sveriges Riksbank.

This year, the winners in medicine, physics and chemistry all share one important distinction: important foundational time spent at UC, a cradle of inventiveness, experimentation and learning. They are:

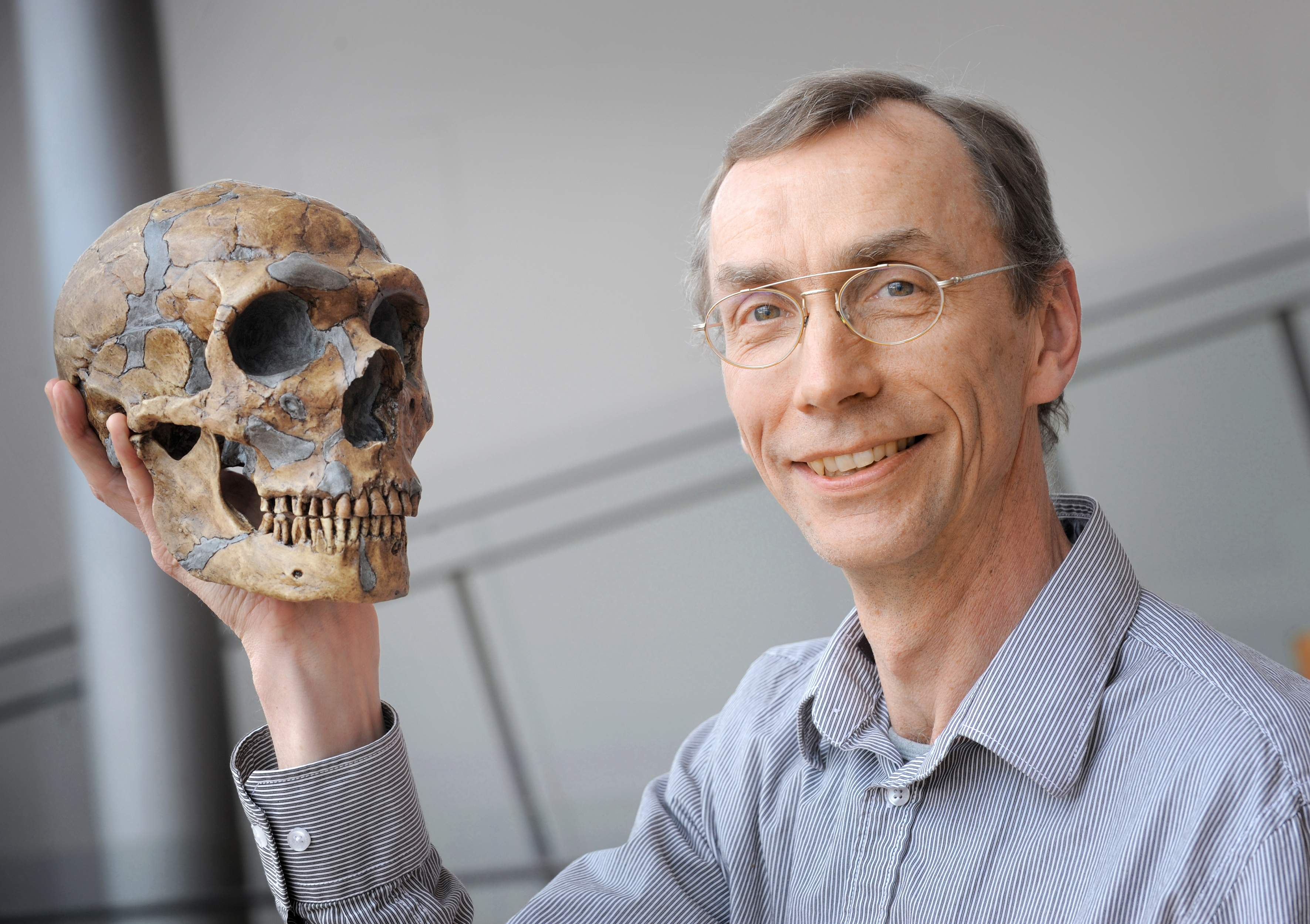

Svante Pääbo, recipient of the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine

Pääbo, the founding director of the Department of Genetics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, was awarded the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for his discoveries concerning the genomes of extinct hominins and human evolution, namely sequencing the entire genome of the Neanderthal — a feat he himself never thought would be accomplished — and the discovery of a previously unknown hominin, Denisova.

Pääbo was as a postdoctoral researcher and collaborator at UC Berkeley, working closely with population geneticist Monty Slatkin on Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA. Read more about one of their groundbreaking studies here: “Neanderthal genome shows evidence of early human interbreeding, inbreeding.”

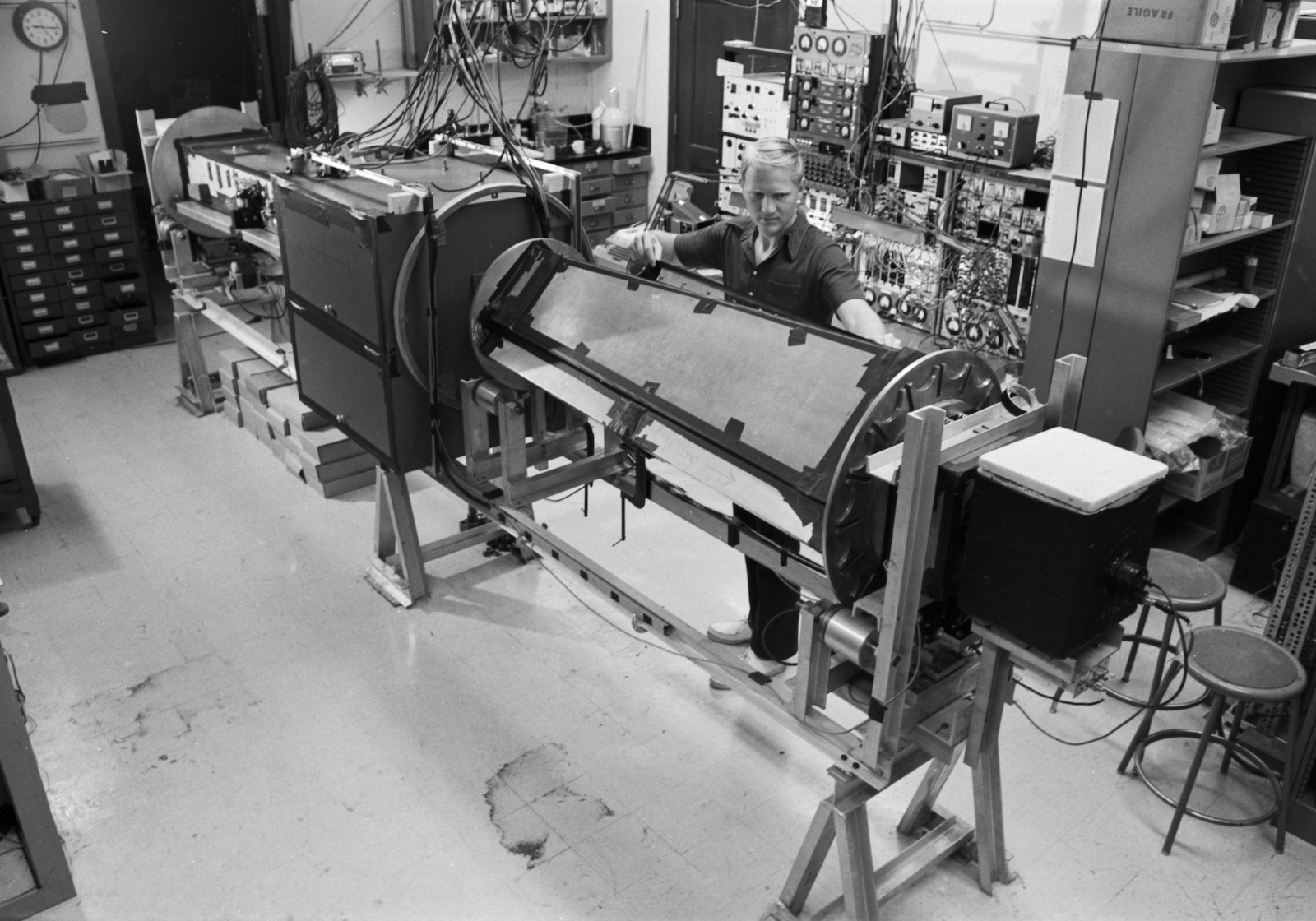

John F. Clauser, recipient of the Nobel Prize in physics

In 1971, Clauser, a postdoctoral researcher working with the late UC Berkeley physicist Stuart Freedman, then a graduate student, got up to an exciting and revolutionary new experiment inside a UC Berkeley basement: testing one of the strangest aspects of quantum mechanics, what Einstein called “spooky action at a distance.” What Clauser and Freedman revealed about the quantum world, namely quantum entanglement, paved the way for stunning new advances in the field and led directly to the Nobel Prize in physics that Clauser received on Oct 4. (Freedman tragically passed away in 2012 and thus was not eligible for an award; Nobels are not awarded posthumously).

Learn more about Clauser’s work as a young scientist in this UC Berkeley piece, quoted below: “Physics Nobel recognizes Berkeley experiment on ‘spooky action at a distance’”:

“That experiment [that Clauser and Freedman conducted in 1971] was the first to show that quantum mechanics really is weird. Two particles, once linked quantum mechanically, or entangled, can be separated by large distances — even the diameter of the universe — and still “know” what happens to one another.

“The research was Freedman’s Ph.D. dissertation in 1972, but he subsequently moved onto a broad range of subfields of physics, all related to quantum mechanics, and died tragically in 2012. Clauser continued to refine the experiment to provide more convincing proof that nature violates what’s called Bell’s inequality and prove that the quantum mechanical description of entangled particles is right.

“That initial experiment at UC Berkeley and the research it spawned were honored today with a Nobel Prize in Physics to Clauser and two others who followed in his and Freedman’s footsteps: Alain Aspect of the Université Paris-Saclay and École Polytechnique in Palaiseau, France, and Anton Zeilinger of the University of Vienna, Austria.”

Clauser spent much of his career at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Both laboratories honored him for his achievement and his lifetime work on Tuesday, and Clauser himself offered reflections on his career in interviews with the labs after taking his long-distance call from Stockholm.

“‘I’m very happy to win the prize, and it took some time for it to be recognized. Many people were skeptical of the research at the time,’ Clauser said in a phone interview. ‘I also am very appreciative of the support of LBNL [Berkeley Lab] decades ago — without that support we would not have not been able to conduct the experiment.’”

Lawrence Livermore National Lab scientists offered their tributes. From “Former Lab physicist earns Nobel Prize in Physics”:

“‘I don’t know Clauser personally, but all of us in quantum information know a fair bit about his experiment and also Alain Aspect’s amazing follow-on experiments in the 1970s and 80s,’ said [Steve] Libby, who works on quantum information. ‘Their work, and Anton Zeilinger’s subsequent terrific work, is foundational to everything we now do.’”

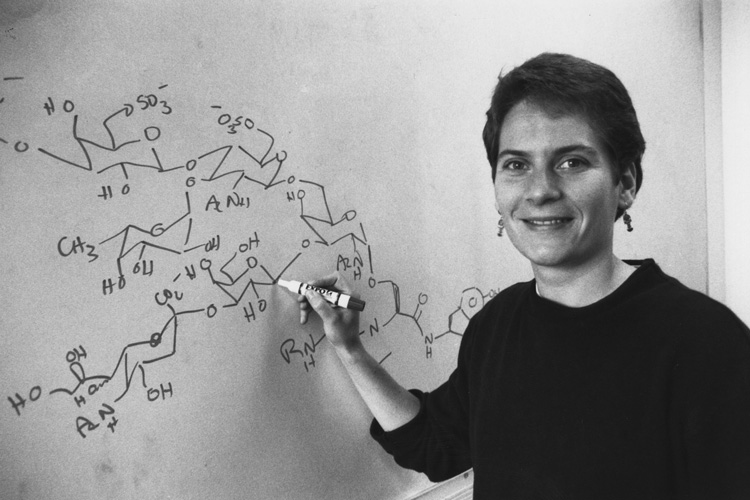

Carolyn Bertozzi, recipient of the Nobel Prize in chemistry

Carolyn Bertozzi, currently a professor at Stanford University, spent her formative years at UC Berkeley and taught on campus until 2015. She earned her Ph.D. in chemistry from the university in 1993 and joined UC Berkeley’s chemistry faculty, and Berkeley Lab, in 1996, after working as a postdoctoral fellow at UCSF. She was also the first director of Berkeley Lab’s Molecular Foundry, a cutting-edge nanoscience research facility. She developed — and named — a field called bioorthogonal chemistry, which stages chemical reactions in cells that do not interfere with biological processes.

From “Chemistry Nobelist Carolyn Bertozzi’s years at UC Berkeley”:

“For 19 years, until 2015 — the year she left to help lead Stanford’s Sarafan ChEM-H institute — [Bertozzi] developed at Berkeley the chemical biology techniques for which she received the Nobel Prize. She calls these techniques bioorthogonal chemistry, building off the “click chemistry” developed by her Nobel Prize co-winners, K. Barry Sharpless of Scripps Research in La Jolla, California, and Morten Meldal of the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.

“’Carolyn Bertozzi is a true trailblazer in chemical biology,’ said Doug Clark, dean of the College of Chemistry. ‘Her lab is among the most prolific in the field, consistently producing innovative and enabling chemical approaches, inspired by organic synthesis, for the study of complex biomolecules in living cells. Carolyn’s work and spirit embody what is best about the scientific tradition and history of the College of Chemistry and of UC Berkeley.’”

Berkeley Lab, whose Molecular Foundry flourished under Bertozzi’s leadership, also offered its praises.

From “Former Berkeley Lab scientist Carolyn Bertozzi wins 2022 Nobel Prize in chemistry”:

“‘Carolyn put the Foundry on the map,’ said Bruce Cohen, a staff scientist in the Foundry’s Biological Nanostructures facility since 2006. ‘She oversaw the opening of the facility, which is a major administrative and scientific feat.’ He added that Bertozzi’s ‘science is so creative and original, as well as technically on point, and it’s opened up entire new areas of study. This is a well-deserved Nobel Prize. I couldn’t be happier for her.’

“Cohen said that Bertozzi is also ‘a great mentor to all of the scientists around her, and has always been an inspirational role model for both women and LGBTQ people in science.’”

Learn more about these trailblazing scientists and their work by visiting the articles above. Special thanks to Robert Sanders, Theresa Duque, Lauren Biron and Anne M. Stark for their coverage at the campuses and labs.

The University of California has a proud legacy of winning Nobel Prizes that stretches all the way back to 1939, when Ernest O. Lawrence was awarded the prize in physics for his invention of the cyclotron. Today, 70 faculty and staff have been awarded 71 Nobel Prizes. Learn more about UC’s Nobel Prize legacy: https://nobel.universityofcalifornia.edu/