Anita Little, UCLA Magazine

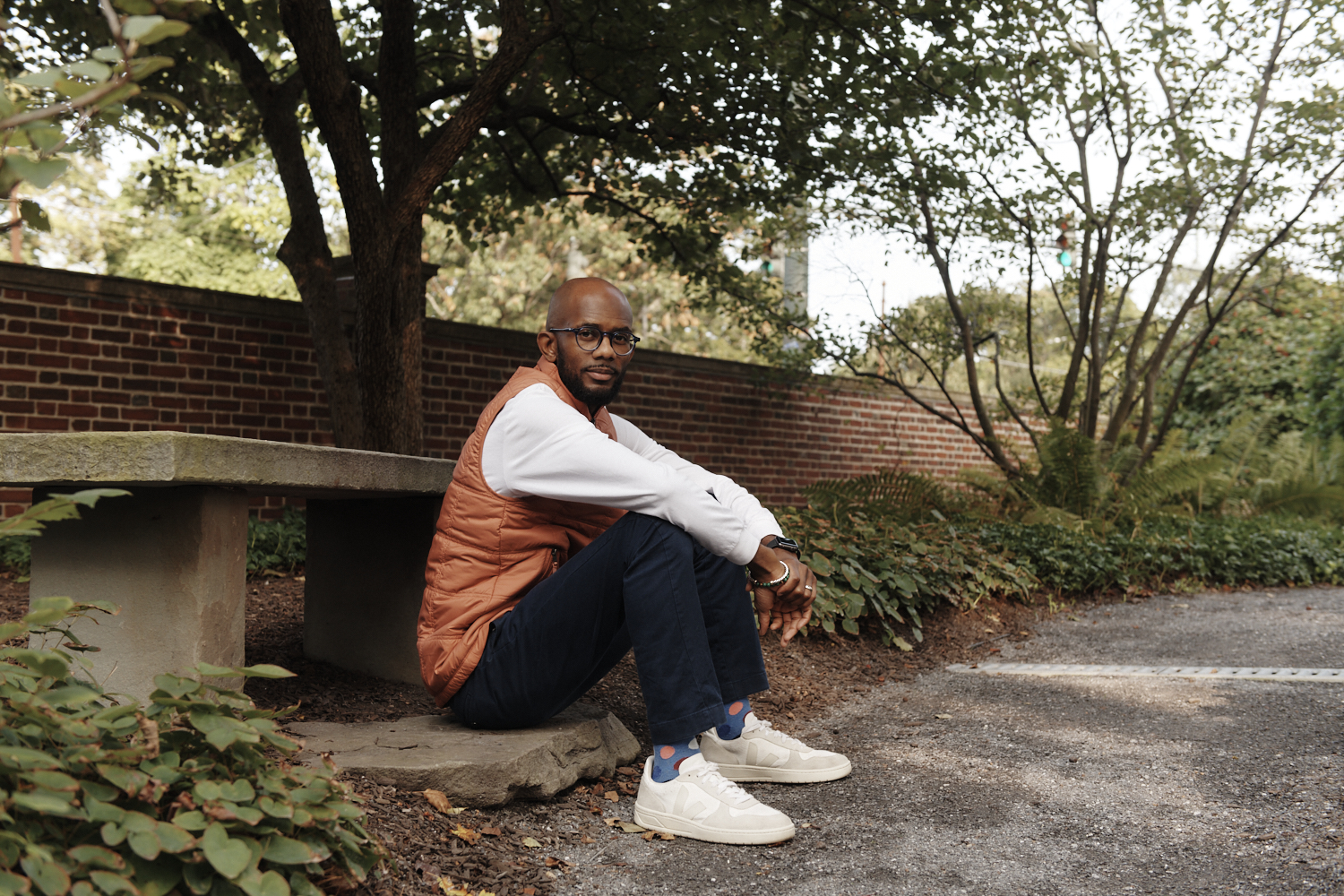

It’s the tail end of summer, and Eddie Cole’s life is in boxes. In his Southern California home, he’s had a frenzied week, packing up his belongings for a cross-country move to Cambridge, Massachusetts. There, he will embark on a yearlong fellowship at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University, which counts Nobel laureate Michael Kremer, Samantha Power, Zadie Smith and U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren as just a few of its past fellows. The year away from Los Angeles will give Cole the gift of time — to think, to imagine.

As a thinker devoted to the field where race, history and education intersect, Cole spends a lot of his time imagining. Growing up in rural Alabama, he attended an all-Black high school that was near a mostly white private school. Referred to as segregation academies, these private schools were formed as a direct response to the Brown v. Board of Education decision. Cole saw, up close, the dynamics of race and schooling laid bare: That experience would prove formative and significant for his future.

Now, Cole is one of the foremost education scholars in the U.S. He is an esteemed associate professor of education and history at UCLA and has been recognized by Education Week as one of the 200 most influential scholars in his field. His stint at Harvard, where he will be given the chance to more deeply pursue his scholarship within its hallowed halls, comes at a striking moment. Earlier this year, the Supreme Court voted in a 6–3 decision to gut affirmative action, upending more than 40 years of precedent that empowered universities to consider race in admissions. And just this month, Claudine Gay was forced to step down as the leader at Harvard, a symbolic setback mired in controversy around issues of free speech, race and politics. Cole’s work becomes especially salient in a time when many students, educators and administrators are fearful of what the future might hold.

Cole believes that to understand the present and change the future, we must first dive into the past. And the upheavals in education over the past year have him thinking more and more about his own past in Greene County, Alabama, as he prepares for this next chapter.

Q: How often do you think about home?

A: Every day. Growing up in the South shaped so much of how I see the world. Being in the South gives you one of the purest views into American life. In my rural public high school, I saw how decisions made more than 50 years prior were impacting how we learned then. I wouldn’t see education, race and history in the same way if I didn’t grow up in Greene County.

Q: In a way, we’re all students of history — unwilling or not — because we live out its consequences. What fascinates you so much about history, race and education?

A: History is so important, and that’s why it’s so interesting to watch elected officials try to shape history and ban what parts of history can be taught. I come from a family of teachers and educators, and what motivated me to study American higher education was how you can look 400 years into the past and see how American colleges and universities have shaped our society.

Higher education has been used as a mechanism to funnel and prepare future lawyers, doctors, politicians — basically our worldmakers. When you look at who has been strategically excluded from colleges and universities from the beginning, you see what a critical role these institutions play in society.

Q: In June, we saw the collapse of four decades of historical precedent when our nation’s highest court decided to effectively end affirmative action. Talk about the effects of this reversal, as well as other recent attacks on equity, diversity and inclusion, and what it means for Black thought.

A: Any time a university is under political control, [it leads to] a bad outcome for students. We should desire and demand that our colleges and universities have a free exchange of ideas. But when we have political interference that limits what is taught and who can be in the classroom, nobody wins.

What’s happening has the potential to reframe social, economic and racial hierarchies. When you have more Black representation in colleges and universities, you have more Black influence, and that means more threats to the status quo. These attacks are about protecting white control of society by way of education. If you can chip away at equity in higher education, you have an opportunity to maintain society as we know it with all of its injustice and unfairness. Ultimately, that’s what’s on the line.

Q: Do you think most people realize what’s on the line?

A: Sometimes the American people are too distracted by the current moment to see the larger picture. This decision will have consequences that reach beyond universities. This is bigger than universities, because it won’t stop at universities. This is going to impact American life, not just Black life, for decades to come. But often people don’t recognize the threat of things like this until it directly impacts them.

Q: And there’s always the question of “Why now?” Affirmative action has always had its opponents, but what’s different about this moment, where opponents have been so successful in these rollbacks?

A: What we’re seeing here is the result of an insidious, decadeslong shift in narrative. How affirmative action is perceived today has moved beyond its original intent. I love to ask students what they think affirmative action means. They will say being able to admit diverse students or make diverse hires. That’s the snapshot of how it’s seen now.

But when President Kennedy moved forward with what would become affirmative action in 1963, it wasn’t about achieving “diversity.” It was about addressing the historical inequities caused by slavery in the United States. It was reparations. But by slowly shifting the narrative away from reparations and toward diversity, opponents were able to obfuscate the original intent of affirmative action.

As the conversation became more about diversity, it became easier to not talk about race. That’s because anyone can see themselves as diverse. Economic class can be diversity. Geography can be diversity. Sexuality can be diversity. You can go down a list of 40 different characteristics that make people “diverse.” And when it becomes about diversity, you talk less about the legacy of slavery, a legacy that has touched every corner of our society.

Q: How should universities be fighting back?

A: Universities should see themselves as thought leaders, not thought reactors. Universities need to be out front saying, “I know what the Supreme Court said, and I know what our state legislators have said. But our values as a university are best represented when we have full representation of our state in our classrooms, when we have full representation of our society teaching our students, and when our administration looks like the people who live in our state.”

Universities have to publicly, vocally say what their values are. My critique is that far too many are quiet right now. Universities have to leave the parameters of academia and go into the community and say that despite what the federal legislation says, we still want to see you in our applicant pool. We still think our university is a place for you to come live, learn and develop into a more robust citizen.

History has so many examples of where academic leaders, presidents, and chancellors weren’t afraid to leave the president's office and actually go into the community. What a real university has to do is think about the city, state and country that it serves, not just the university’s own interests.

Q: We can’t talk about affirmative action without also talking about legacy admissions, which has been referred to by some, like U.S. Rep. Barbara Lee, as affirmative action for white people. Could what’s happening to affirmative action give renewed attention to legacy admissions?

A: We’re seeing that immediately. In the wake of the Supreme Court decision, there have already been some legal filings against legacy admissions. People are beginning to rethink the entire system and examine it more critically. That’s what has me excited about this moment, because as damning as that Supreme Court decision was, it was a clear wake-up call for how we need to overhaul the entire university system. People now have the motivation to think in a way they haven’t thought before.

Q: You’re at Harvard this year for the prestigious Radcliffe Fellowship, where you’ll work on a new book about race and education. What made you choose Harvard? And what do you hope for most from this opportunity?

A: Early in my career, I had a game-changing fellowship and it gave me a gift of time. I was able to write my first book and take a moment to think, removed from teaching and advising. And that’s what I’m most excited for at Harvard — the chance to step back, look at the world and see how history is at the center of it.

Q: Since you've been at Harvard, its president, Claudine Gay, has been forced to step down. Any thoughts on that?

A: There is broadening political interference with academia. The past few months have demonstrated public questioning of academic leaders from the political right and center left. There is broad distrust — and that should cause academic leaders and faculty members to be more proactive in safeguarding the future of higher education before those outside academia do it for us.

Read more from UCLA Magazine’s Winter 2024 issue.