Edward Lempinen, UC Berkeley

Annette Miller has lived much of her life in a two-story clapboard house in West Oakland, and through the decades she has seen the fortunes of her neighborhood rise and fall. But surging violence here has left a devastating personal impact: one son murdered, another son shot in the head and permanently disabled.

It seems impossible, but Miller has built strength from these tragedies, and has emerged as a community leader and educator honored for her volunteer work. And so, when she was invited to join in a novel neighborhood safety project organized by the Possibility Lab at UC Berkeley, she embraced the opportunity.

“When I got involved in safety in our community, it was all around losing a child to gun violence,” she said in a recent interview on her front porch. “It comes from understanding the value of your kids, and the pain of our community.

“My main focus has been making sure that the community gets the opportunity of being comfortable and safe. When people come to me, I’m educating them on getting crosswalks, keeping the parks clean so kids and people can come out and enjoy the space, working with the seniors.”

Miller’s approach closely parallels the strategy envisioned by the Firsthand Framework for Policy Innovation, a program launched by the Possibility Lab. In dozens of focus groups and meetings across some of Oakland’s most troubled neighborhoods, the project has looked beyond police patrols and arrest rates to understand how residents themselves think about safety and security.

“Fundamentally, our idea is that the people who are closest to social problems have a unique expertise that we can tap into in order to solve the problems,” said Amy E. Lerman, the lab’s executive director. “When we don't include them in the conversations around how to understand the problems they face, or how to solve those problems, we're really losing this incredible, rich source of knowledge that comes from their everyday lived experience.”

Lerman founded the Possibility Lab as a multidisciplinary team of policy researchers and practitioners who work with government and community partners to develop and test data-driven policy ideas that serve the public good.

The Firsthand Framework project started three years ago, the brainchild of Lerman and her former Berkeley political science classmate Naomi Levy, now an associate professor at Santa Clara University and director of community engaged research at the Possibility Lab. Drawing on ideas developed in faraway war zones, and working with allied community groups and Oakland’s Department of Violence Prevention, they are conducting an ambitious exercise in grassroots democracy.

It’s based on a deceptively simple question: What does it take to make you feel safe in your community?

What local residents told Berkeley researchers is that individual public safety problems – gang violence or prostitution, for example — have complex dynamics, and addressing them might involve not just policing, but also addressing poverty, education, mental health and other areas.

The challenge now is to adapt this understanding to make the most effective public policies for public safety.

Violence intrudes on a lush green park

One of the core partners in the Possibility Lab project is Trybe, an Oakland non-profit. On a gray, blustery late-winter afternoon, Trybe Executive Director Andrew Park and his colleague, Hector Cruz, are keeping a watchful eye on four square blocks of sloping green space that is the focus of their work.

This is San Antonio Park, Trybe’s base of operations. From a makeshift complex of tents and gray-washed shipping containers near the old tennis courts, staffers and volunteers distribute food, provide a safe play space for kids, hold cultural events for the surrounding community. They help out neighbors who need housing or medical services.

But the park is also a flashpoint for gang rivalries and, sometimes, violence. Park and Cruz worry over gang tags sprayed onto trees and garbage bins. Just the day before, Cruz explains, Trybe “violence interrupters” had been called to a fight at the park that was escalating dangerously.

“We have 500 shootings a year in Oakland,” says Park, who holds a doctorate of ministry from the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley. “That happens because people are desperate and they're — you know, it's insane to actually pull the trigger on somebody. That just goes to show how much of an apocalyptic state we’re in, and how disconnected we all are.”

Down the hill, in a neighborhood known as Little Saigon, Chien Nguyen is standing in front of the café he owns on the edge of Clinton Park. But the neighborhood’s health has declined sharply, and Nguyen, after eight years of hard work, recently closed his doors.

Many Oakland residents "are calling for a very different kind of response to crime and violence that they see in their own neighborhoods and daily lives," said Amy E. Lerman, founder of the Possibility Lab at UC Berkeley.

There’s a homeless man sitting in his doorway, and the tents of homeless people line nearby streets. A few days ago, Nguyen helped a woman who had given birth in one of the tents. The city park across the street is in a state of extreme neglect. It’s been forever since he saw children playing there.

International Boulevard, just a couple of blocks west, is notorious for its open prostitution. Even on a cold late-winter afternoon, women are standing on corners, in front of shops, soliciting trade. Nguyen is deeply concerned that parents driving their children to and from nearby Franklin Elementary School have to pass such shocking scenes.

Both Park and Nguyen see similar dynamics at work: Local government doesn’t have the resources to provide even basic services like youth programs or support for the homeless. Community groups who try to fill the gaps are constantly battling for funds.

And that, they say, is one of the key attributes of the Possibility Lab project: It empowers residents and neighborhood advocates by helping to build connections.

The murder of George Floyd, and the urgent call for change

This is not the first team of university researchers to come into an Oakland neighborhood looking for data. Ask Miller, ask Park — usually the academics parachute in, gather what they need, and disappear back to campus. And so when the Possibility Lab started to visit Oakland neighborhoods in mid-2021, the team was met with skepticism.

From the start, though, project researchers worked to be different.

The inspiration, Lerman explained, came from Everyday Peace Indicators, a U.S. nonprofit that works in overseas communities destabilized by violent conflict. The goal is to understand what residents want, and to work from the grassroots up to build a vision for peace.

The Firsthand Framework emerged from a two-year statewide project called California 100, where Lerman served as director of innovation. The police murder of George Floyd in May 2020 was still fresh in everyone’s mind, and organizers were looking for ways to innovate a better future for the state. As a professor at Berkeley’s Goldman School of Public Policy, her research has focused on crime, violence and justice.

The Firsthand Framework project in Oakland “was a way of recognizing that the Black Lives Matter conversation and the police reform conversation really have been led by these communities and community organizations,” Lerman explained. “They are calling for a very different kind of response to crime and violence that they see in their own neighborhoods and daily lives.”

People don’t want conventional answers to crime and violence

At first glance, the Firsthand Framework approach is all about data. Levy, Lerman and their colleagues were looking for a way to define and measure what the public wanted, and then use that data to achieve a measurable impact on safety in some of Oakland’s toughest neighborhoods.

Naomi Levy, the Possibility Lab's director of community engaged research, plays a critical role in leading the lab's work with Oakland residents and community groups. She earned her Ph.D. at Berkeley and now is on the faculty at Santa Clara University.

After extensive talks, they set partnerships with Trybe and five other community organizations, plus the city’s Department of Violence Prevention (DVP). The mix helped them to reach a range of residents in different Oakland communities: people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds, refugees and immigrants, young women at risk of sexual exploitation, young people who had been incarcerated, seniors and others.

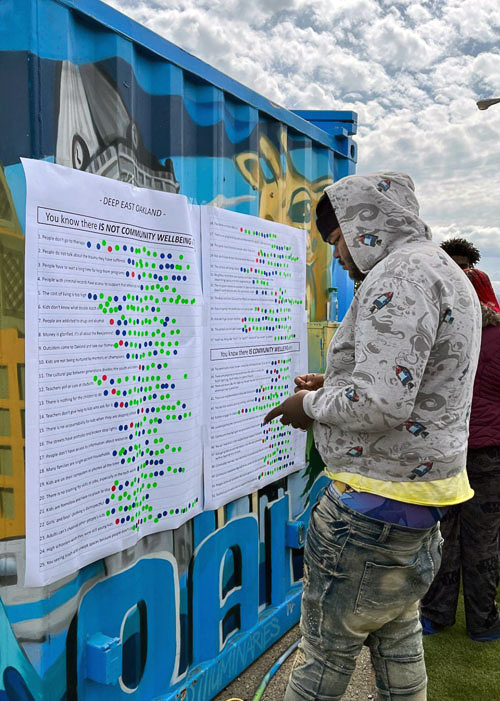

Over the ensuing months, the project organized two dozen focus groups and a series of larger town halls. Hundreds of city residents participated in a process that explored specific indicators of distress and safety in their neighborhoods.

In the background, the researchers were constantly working to build trust — and, in the view of West Oakland community leader Annette Miller, that work paid off.

How could she tell? Because people kept attending the meetings. Older residents, who might’ve been skeptical at the start, kept coming back. Young people, famously difficult to engage in this sort of process, kept coming back. Sometimes the older people met with the young people, a crucial nexus when the topic is neighborhood crime and safety.

“People really got to trust you, and they really got to know you to believe in what you’re doing,” said Miller, who chairs a residents’ council in the Hoover-Foster neighborhood. “This part of West Oakland has to know that you are doing the work in order for them to come into the space that you represent.”

The practical wisdom that resides even in troubled communities

By the end of 2023, the organizers and partners distilled nearly 600 “firsthand indicators” of community safety from the focus groups and town hall meetings. In a recent report, they detailed indicators in a range of categories: the physical spaces in a community, for example, the well-being of young people, health, and economic security.

Some of the indicators were negative, and some were positive. On policing, some residents cited the tendency of officers to be more aggressive with people of color, or the number of people they know who had been killed by police. Others cited officers who walk around the community and get to know the people living there.

Among communities of immigrants, it was a negative indicator that people who aren’t fluent in English or Spanish felt that their children suffered discrimination at school. But it’s a positive indicator to have neighbors of shared origins who look out for each other.

If there’s one main takeaway, said Trybe director Park, it’s that people want a holistic approach to safety and security.

Looking at the findings line by line, a reader might conclude, “ ‘Oh, we just need more police,’ ” Park said. “Well, people are saying that, but that's not quite what they're actually saying. They're saying that they want a certain level of policing, so that the crazy stuff is taken care of. But they don't want the resources all going to police, where there's nothing for youth and children and families and seniors.”

A potential impact far beyond Oakland

Word of the project’s early success has spread quickly: Political and policy leaders in Sacramento and beyond have already expressed interest. A new interactive website makes the data available to everyone.

Lerman says the Lab is exploring real-world applications of the Firsthand Framework for complex challenges in various locations: health indicators among farmworkers in California’s Inland Empire. Homelessness in the Bay Area. Interventions for opioid use disorder in Oregon and mental health crises in Texas.

In Oakland, the work is in some senses just beginning. The Firsthand Framework partners are in the early stages bringing residents’ insights into programs and city policies that actually reduce crime and leave people feeling safer.

The Oakland Department of Violence Prevention (DVP) is a crucial partner in this work. Daniela Medina, who earned a Berkeley master’s degree in 2021, is a deputy chief, and she sees broad possibilities for using the indicators.

DVP’s violence interrupters are similar to those at Trybe. They might intervene in an emergency, Medina explained, but afterward, they work to engage the those involved in the conflict and guide them to a safer path. They may need resources or other types of support. That, she said, is where the Berkeley project comes in.

“We’re working with the Possibility Lab not only to identify how some of the indicators can be applied to solutions, but also to pilot some of these ideas,” Medina said. “These might be really small things like cleaning up a particular corner of a park or bringing young people together.... Or there might be larger-scale solutions.”

But the partnership works on another level, too. Berkeley’s expertise and credibility may help DVP and community advocates to win support from Oakland political leaders.

The gritty, grassroots work of democracy

In a moment of crisis for democracy in the U.S. and worldwide, the partnerships and processes of the Firsthand Framework project stand out as an exercise in building community power from the ground up. But in Oakland neighborhoods that historically have been disenfranchised, it’s a major advance that anyone in power wants to hear their voices.

“People may think of it in terms of, ‘Somebody actually cares enough to ask me,’ ” Medina said. “It may be one of the first times that they are involved in civic engagement, where they are getting to share what is actually working for them, what's important to them.”

Some early signals suggest that the democratic values encouraged by the project are already filtering down to the street level.

In Little Saigon, Chien Nguyen works for Trybe now. With his café closed, most days he’s collecting garbage from the streets and filling two dumpsters provided by the city. But that’s also an exercise in meeting people, talking to them about neighborhood problems, building networks.

Trybe has agreed to take over management of the Clinton Park Community Center, and there are plans to make it a place that’s safe for kids. Nguyen and others, working through the San Antonio Neighborhood Coalition, have developed a proposed policy on sex trafficking and have been meeting with Oakland and Alameda County officials to discuss implementation. On Saturday, April 27, the coalition will host a community action on sex trafficking with local political leaders and allies.

In West Oakland, Annette Miller is now working with DVP on social events focused on community safety, and she believes that the Firsthand Framework really can lead to change. Policies and funding are essential, she says, but empowerment begins with hope.

“If you come out and you’re able to express yourself in a meeting,” Miller said, “and if you let folks know that something has been a concern of yours, you might see that it's not just you, but two or three other people had this same problem. So when you understand that, and you have that compassion, your mind is free. Then you know that you can accomplish more than what you thought before.”

A young man at an Oakland event evaluates a list of positive and negative indicators of community well-being and how others had ranked them.