Robert Sanders, UC Berkeley

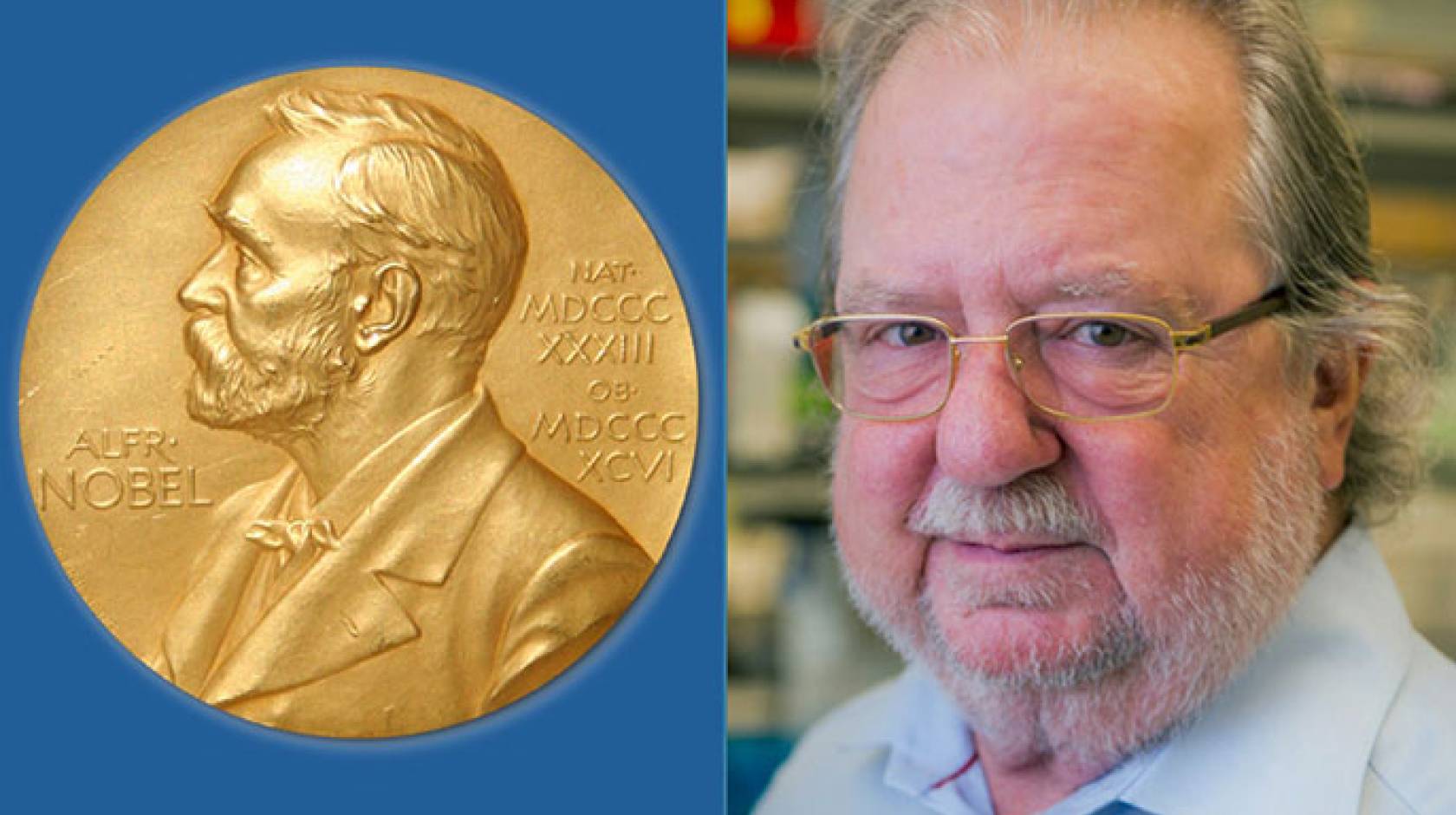

Immunologist James P. Allison today shared the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for groundbreaking work he conducted on cancer immunotherapy at the University of California, Berkeley, during his 20 years as director of the campus’s Cancer Research Laboratory.

Allison, who is now at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, shared the award with Tasuku Honjo of Kyoto University in Japan “for their discovery of cancer therapy by inhibition of negative immune regulation.”

Credit: Nobel Prize

Allison, 70, conducted basic research on how the immune system — in particular, a cell called a T cell — fights infection. His discoveries led to a fundamentally new strategy for treating malignancies that unleashes the immune system to kill cancer cells. A monoclonal antibody therapy he pioneered was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2011 to treat malignant melanoma, and spawned several related therapies now being used against lung, prostate and other cancers.

“Because this approach targets immune cells rather than specific tumors, it holds great promise to thwart diverse cancers,” the Lasker Foundation wrote when it awarded Allison its 2015 Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award.

Allison’s work has already benefited thousands of people with advanced melanoma, a disease that used to be invariably fatal within a year or so of diagnosis. The therapy he conceived has resulted in elimination of cancer in a significant fraction of patients for a decade and counting, and it appears likely that many of these people are cured.

“Targeted therapies don’t cure cancer, but immunotherapy is curative, which is why many consider it the biggest advance in a generation,” Allison said in a 2015 interview. “Clearly, immunotherapy now has taken its place along with surgery, chemotherapy and radiation as a reliable and objective way to treat cancer.”

“We are thrilled to see Jim’s work recognized by the Nobel Committee,” said Russell Vance, the current director of the Cancer Research Laboratory and a UC Berkeley professor of molecular and cell biology. “We congratulate him on this highly deserved honor. This award is a testament to the incredible impact that the fundamental research Jim conducted at Berkeley has had on the lives of cancer patients”

“I don’t know if I could have accomplished this work anywhere else than Berkeley,” Allison said. “There were a lot of smart people to work with, and it felt like we could do almost anything. I always tell people that it was one of the happiest times of my life, with the academic environment, the enthusiasm, the students, the faculty.”

Credit: IVRI

In fact, Allison was instrumental in creating the research environment of the current Department of Molecular and Cell Biology at UC Berkeley as well as the department’s division of immunology, in which he served stints as chair and division head during his time at Berkeley, said David Raulet, director of UC Berkeley’s Immunotherapeutics and Vaccine Research Initiative (IVRI).

“His actions helped create the superb research environment here, which is so conducive to making the fundamental discoveries that will be the basis of the next generation of medical breakthroughs,” Raulet said.

Self vs non-self

Allison joined the UC Berkeley faculty as a professor of molecular and cell biology and director of the Cancer Research Laboratory in 1985. An immunologist with a Ph.D. from the University of Texas, Austin, he focused on a type of immune system cell called the T cell or T lymphocyte, which plays a key role in fighting off bacterial and viral infections as well as cancer.

Credit: Roxanne Makasdjian and Stephen McNally/UC Berkeley

At the time, most doctors and scientists believed that the immune system could not be exploited to fight cancer, because cancer cells look too much like the body’s own cells, and any attack against cancer cells would risk killing normal cells and creating serious side effects.

“The community of cancer biologists was not convinced that you could even use the immune system to alter cancer’s outcome, because cancer was too much like self,” said Matthew “Max” Krummel, who was a graduate student and postdoctoral fellow with Allison in the 1990s and is now a professor of pathology and a member of the joint immunology group at UCSF. “The dogma at the time was, ‘Don’t even bother.’ ”

“What was heady about the moment was that we didn’t really listen to the dogma, we just did it,” Krummel added. Allison, in particular, was a bit “irreverent, but in a productive way. He didn’t suffer fools easily.” This attitude rubbed off on the team.

Trying everything they could in mice to tweak the immune system, Krummel and Allison soon found that a protein receptor called CTLA-4 seemed to be holding T cells back, like a brake in a car.

Postdoctoral fellow Dana Leach then stepped in to see if blocking the receptor would unleash the immune system to actually attack a cancerous tumor. In a landmark paper published in Science in 1996, Allison, Leach and Krummel showed not only that antibodies against CTLA-4 released the brake and allowed the immune system to attack the tumors, but that the technique was effective enough to result in long-term disappearance of the tumors.

“When Dana showed me the results, I was really surprised,” Allison said. “It wasn’t that the anti-CTLA-4 antibodies slowed the tumors down. The tumors went away.”

After Allison himself replicated the experiment, “that’s when I said, OK, we’ve got something here.”

Checkpoint blockade

Credit: Jane Scherr/UC Berkeley

The discovery led to a concept called “checkpoint blockade.” This holds that the immune system has many checkpoints designed to prevent it from attacking the body’s own cells, which can lead to autoimmune disease. As a result, while attempts to rev up the immune system are like stepping on the gas, they won’t be effective unless you also release the brakes.

“The temporary activation of the immune system though ‘checkpoint blockade’ provides a window of opportunity during which the immune system is mobilized to attack and eliminate tumors,” Vance said.

Allison spent the next few years amassing data in mice to show that anti-CTLA-4 antibodies work, and then, in collaboration with a biotech firm called Medarex, developed human antibodies that showed promise in early clinical trials against melanoma and other cancers. The therapy was acquired by Bristol-Myers Squibb in 2011 and approved by the FDA as ipilimumab (trade name Yervoy), which is now used to treat skin cancers that have metastasized or that cannot be removed surgically.

Meanwhile, Allison left UC Berkeley in 2004 for Memorial Sloan Kettering research center in New York to be closer to the drug companies shepherding his therapy through clinical trials, and to explore in more detail how checkpoint blockade works.

“Berkeley was my favorite place, and if I could have stayed there, I would have,” he said. “But my research got to the point where all the animal work showed that checkpoint blockade had a lot of potential in people, and working with patients at Berkeley wasn’t possible. There’s no hospital, no patients.”

Thanks to Allison’s doggedness, anti-CTLA-4 therapy is now an accepted therapy for cancer and it opened the floodgates for a slew of new immunotherapies, Krummel said. There now are several hundred ongoing clinical trials involving monoclonal antibodies to one or more receptors that inhibit T cell activity, sometimes combined with lower doses of standard chemotherapy.

Antibodies against one such receptor, PD-1, which Honjo discovered in 1992, have given especially impressive results. Allison’s initial findings can be credited for prompting researchers, including Allison himself, to carry out the studies that have demonstrated the potent anti-cancer effects of PD-1 antibodies. In 2015, the FDA approved anti-PD-1 therapy for malignant melanoma, and has since approved it for non-small-cell lung, gastric and several other cancers.

Science magazine named cancer immunotherapy its breakthrough of 2013 because that year, “clinical trials … cemented its potential in patients and swayed even the skeptics. The field hums with stories of lives extended: the woman with a grapefruit-size tumor in her lung from melanoma, alive and healthy 13 years later; the 6-year-old near death from leukemia, now in third grade and in remission; the man with metastatic kidney cancer whose disease continued fading away even after treatment stopped.”

Allison pursued more clinical trials for immunotherapy at Sloan-Kettering and then in 2012 returned to his native Texas.

Born in Alice, Texas, on Aug. 7, 1948, Allison earned a B.S. in microbiology in 1969 and a Ph.D. in biological science in 1973 from the University of Texas, Austin.