Julia Busiek, UC Newsroom

The University of California made an impressive showing on TIME magazine’s list of the best inventions of 2023. The latest installment of the annual collection was released last week and recognizes four inventions developed or advanced in UC laboratories among 200 products that TIME’s editors describe as “changing how we live, work, play, and think about what’s possible.”

Read on to discover the four inventions honored by TIME, or dig deeper into the world-changing innovations that have emerged from UC’s $7.5 billion research enterprise.

Where there’s smoke

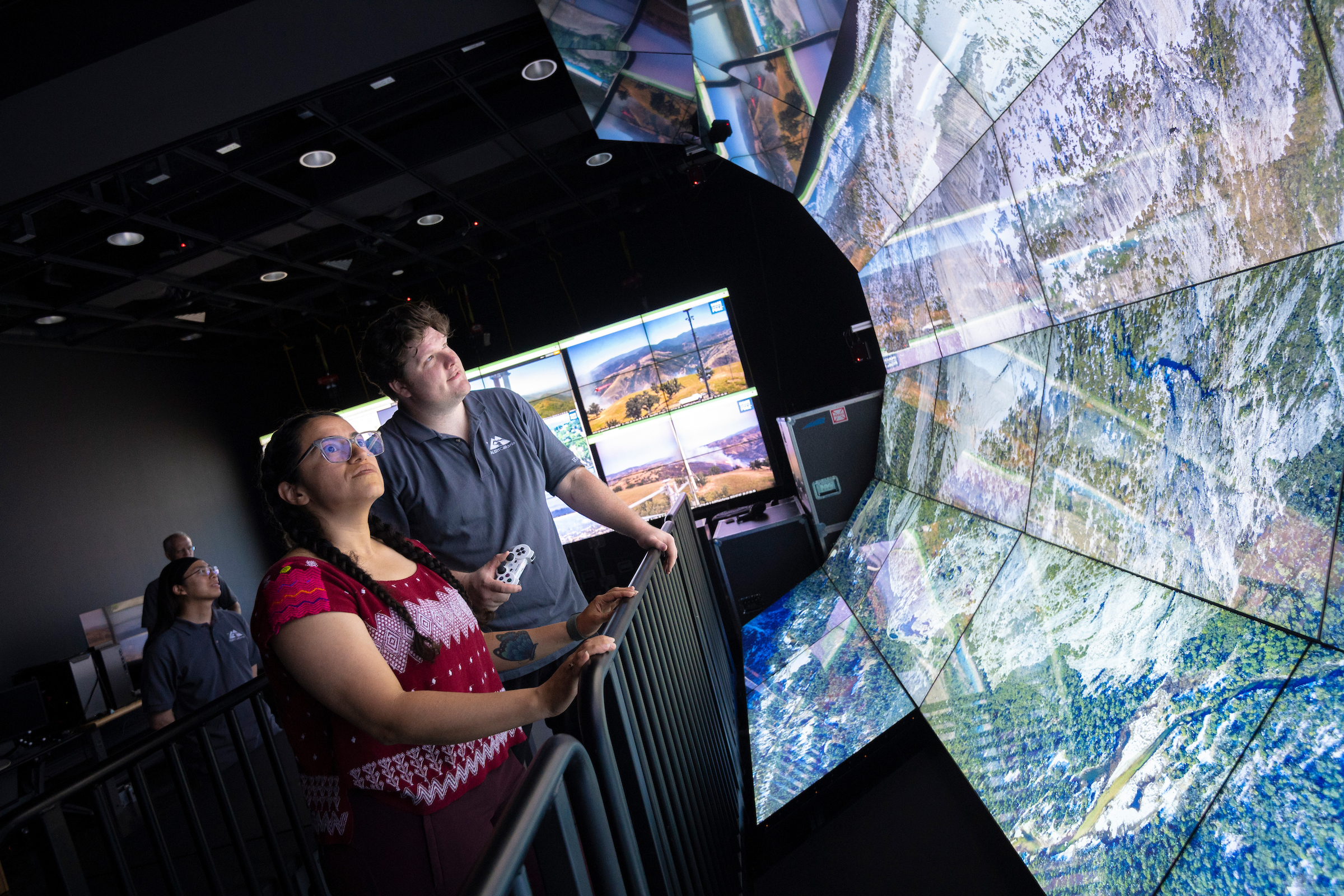

Keeping an eye out for wildfires across California’s vast and varied terrain has been a herculean task since the days of the lone fire spotter perched in a mountaintop lookout cabin. As climate change fuels more and bigger fires statewide, containing fires before they grow out of control has never been more important. Now, a program called ALERTCalifornia is bringing the futuristic power of artificial intelligence to the age-old job of fire spotting.

To create the project, a team from UC San Diego, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection and software company Digital Path utilized ALERTCalifornia's more than a thousand high-definition cameras across the state. Live and archived footage is used train AI to detect smoke that appears in the frame. When the system spots something that it recognizes as a fire, it alerts firefighters keeping watch. Once the incident is confirmed, firefighters head out to monitor or fight the fire before it spreads. Unlike human observers in airplanes or lookout towers, ALERTCalifornia’s AI never sleeps, and it can spot signs of fire 60 miles off during the day and 120 miles away on a clear night.

In September, for instance, a camera near Grass Valley picked up a smoke signal at 5:19 in the morning. Firefighters were already on scene before the first 911 call came in from a nearby resident who’d noticed the smoke, and the fire never spread beyond a quarter of an acre.

Read more: ALERTCalifornia and CAL FIRE’s Fire Detection AI Program Named One of TIME’s Best Inventions of 2023 (UC San Diego)

Stopping Wildfires (TIME)

Zapping the carbon out of seawater

To slow the pace of climate change, we don’t just need to stop emitting carbon into the atmosphere as quickly as possible. We also need to draw out the excess that’s been accumulating since the start of the Industrial Revolution, pushing the concentration of atmospheric carbon to a 3-million-year high.

Seawater is like a potent carbon sponge, able to hold vastly higher concentrations of carbon than the atmosphere. Our oceans exist in equilibrium with our skies: the more carbon in the air, the more the oceans absorb. By that logic, if we can pull carbon out of seawater, we can increase seawater’s capacity to pull carbon out of the atmosphere.

A team of engineers led by Gaurav Sant at UCLA’s Samueli School of Engineering built a mechanical system to do just that. The contraption zaps seawater with electricity, kicking off a chain of chemical reactions that causes the dissolved carbon to precipitate out as a solid, so it can’t contribute to global warming. One of the reaction’s byproducts is pure hydrogen, a climate-friendly fuel that can in turn generate the electricity needed to run the reaction.

Sant cofounded the startup Equatic to market the technology, and this year they installed their first commercial systems in Los Angeles and Singapore.

“Ocean water already contains 150 times more carbon dioxide than the air, and Equatic’s rinse-and-repeat flow-electrolysis process allows the oceans to serve as an enormous reservoir of CO2,” said Dante Simonetti, an associate professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at the Samueli School of Engineering. “This allows the approach to scale at globally relevant rates faster and cheaper than traditional direct air capture and related methods.”

Read more: Time picks UCLA Engineering climate solution as one of 2023’s top inventions (UCLA)

Optimizing the Oceans (TIME)

Avocado upgrade

If you’ve ever found yourself stalled in front of a teetering pyramid of avocados in the produce aisle, gingerly squeezing every third or fourth fruit, hoping through some combination of diligence, luck and extrasensory perception to pick the one that will be ripe when you need it for dinner three days from now, you’re in luck: horticulturalists at UC Riverside have bred an avocado that tells you when it’s ready to eat.

The Luna UCR will taste familiar to fans of the near-ubiquitous Hass, the dominant avocado variety sold in the United States. But unlike its popular cousin, the Luna’s skin turns uniformly black when it’s ripe, taking the guesswork out of grocery shopping and cutting down on food waste and grocery bills. Compared to the Hass, the Luna can grow the same amount of fruit from a smaller tree, saving growers space and time in their orchards. It stays fresh and firm for the long journey from the tree to your cart. And arguably most importantly, its nutty flavor and smooth texture make it ideal for guacamole.

The Luna is the fruit of decades of labor from UC’s 80-year-old avocado breeding program. Growers around the world got their first shipments of Luna trees earlier this year, so it’ll be a few years until they’re producing avocados and shipping them to a grocery store near you.

Read more: Luna UCR avocado is one of TIME's '2023 best inventions' (UC Riverside)

Next-gen Avocado (TIME)

A second life for seafood industry waste

Speaking of that long journey your food takes to your grocery cart: much of it makes the trip packed in Styrofoam, a single-use petroleum-based product that takes 500 years to decompose. To cut down on the burgeoning problem of plastic pollution and its threats to marine life, UC Santa Cruz professor and chair of Electrical and Computer Engineering Marco Rolandi devised a Styrofoam alternative called Cruz Foam that can decompose in your backyard compost pile in just a few weeks.

Rolandi and his coinventor John Felts solidified a friendship over their shared love of the ocean, and their invention makes use of the ocean’s bounty. Their foam comes from chitin, the hard stuff that forms shellfish shells and bug exoskeletons. Cruz Foam gets its shrimp shells from sustainable fisheries. That keeps both the shells and the Styrofoam they replace out of landfills.

Read more: Sustaining the Cold Chain (TIME)

The Luna UCR™ avocado