Nicole Freeling, UC Newsroom

A few years ago, college was not in the picture for AnDrea Crawford, a 46-year-old who was busy raising three kids and running an East Oakland hair salon.

Today, she’s finishing up a UC Berkeley degree in legal studies — an accomplishment that she says would never have been possible without the federal aid program known as the Pell Grant.

After learning that her youngest had autism, she decided to hang up her trimming shears and go to college to gain the knowledge and resources to be a more effective advocate for children with neurological differences. She enrolled in classes at Laney College and Merritt College in Oakland, earning associate degrees in English and psychology before transferring to UC Berkeley in 2017.

“Going to a school like UC Berkeley wasn’t something I even had on my radar. I never imagined it was something I could afford,” Crawford said.

Crawford was surprised to discover that her tuition and fees were covered by financial aid, including Pell Grant funds that never needed to be repaid.

“Now that I’ve had these doors opened to me, I have an obligation to walk through them and make a difference,” she said. “I can see my research making it all the way to Congress to get something stamped and changed.”

Courtesy photo

The Pell Grant program that has been so instrumental in Crawford’s success was launched in 1965 to ensure that any student with the desire to go to college could do so. Over the years, this vital program has become the foundation of federal financial aid, helping more than 7 million low-income students a year attend college.

At UC, roughly a third of all undergraduates depend on Pell Grants — about 78,000 students in all.

Like Crawford, these students bring unique real-life experiences to their research and scholarship. And many use their college education to give back to their communities in myriad ways.

But the Pell Grant program, which once covered a major share of students’ tuition, has failed to keep up with inflation. Today, it covers only a fraction of educational expenses. As a result, more students take on debt, struggle to pay for basic needs such as food and housing — or forgo their college dreams altogether.

The University of California and the UC Student Association have partnered with college access groups and student associations across the country to speak out about the issue — and to call on Congress to recommit to this vital program.

The Double the Pell campaign has set a target of increasing the maximum Pell Grant award from today’s $6,345 to $13,000 by 2024.

“Higher education has been the bedrock of the American Dream: The idea that if you study, work hard and have the curiosity and ambition to go to college, you can do that,” said UC Student Association President Aidan Arasasingham, a global studies major at UCLA. That dream, he said, has been disappearing with dwindling federal support.

Courtesy photo

“Reinvesting in higher education is key not only to bringing this country out of the pandemic, but bringing it into the 21st century and to building back what has been a core part of American excellence.”

The UC and UCSA Double the Pell campaign is an extension of the university’s commitment to make a world-class education accessible and affordable to all hardworking students, regardless of economic means.

UC has been so successful in serving large numbers of low-income and first-generation students that The New York Times referred to it as “California’s upward mobility machine.” It enrolls a higher percentage of low-income students than any of its public or private peer institutions. Three of its campuses — UC Davis, UC Irvine and UC San Diego — each enroll more Pell students than the entire Ivy League combined.

“The University of California has a longstanding record of investing in financial aid and student success,” said UC President Michael V. Drake, M.D. “However, UC cannot do this alone. We need impactful, long-term support for students and for higher education across the country; we need Congress to double the Pell as a down payment on America’s future.”

A disappearing benefit

Pell Grants, the primary way the federal government helps low-income students afford college, are generally available to students from families who make $50,000 or less a year.

The program was launched with the intent of covering the bulk of a student’s education. And for many years it did just that.

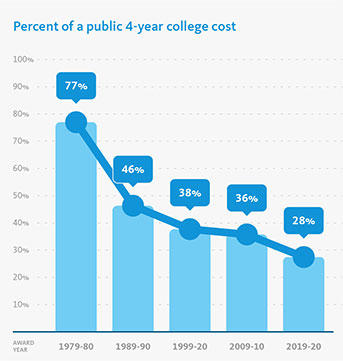

In 1980, Pell Grants covered more than 75 percent of a student’s costs for a four-year public college. But since then, their purchasing power has eroded significantly due to inflation and other factors, including a decrease in state investment in public higher education.

As a result, the Pell Grant now covers just over a quarter of the cost of an average public four-year education.

Data aggregated from U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, College Board and other sources.

Students fill in the gaps by taking on greater student loan debt; they work longer hours at jobs outside of school; and they scramble to meet other basic needs, such as rent, groceries, transportation and child care to cover tuition costs.

The coronavirus has compounded these hardships, increasing the number of college students facing financial strain and eliminating many of the supports they rely upon — such as friend networks and on-campus jobs.

“Even with financial aid, I’m always strapped. I’m always keeping an eye on my bank account just to see if I can pay the rent,” said Graciela Serratos, a UC Berkeley interdisciplinary studies major who is studying how colleges can better serve formerly incarcerated students.

After transferring to UC Berkeley from Sacramento City College, Serratos worked 25 hours a week at two part-time jobs just to cover living expenses. But both her grades and health have been hurt by juggling work hours with class schedules and studying.

To save money, she moved into a studio apartment with her partner. When COVID-19 hit, the space was just too small for two people working and taking classes remotely. Now they are in a more expensive, one-bedroom apartment — and Serratos is covering all the rent since her partner was laid off.

“COVID has just made everything that much harder,” she said.

Expanding aid to more students

Nationally, reinvesting in Pell would put more money into the hands of students to cover their education and basic needs. The increased funding would enable students to reduce outside work hours, take on less debt, and have greater security in being able to afford their education — all factors critical to their educational success.

At UC, it would also enable the university to stretch its own aid dollars to cover more students.

Under its Blue and Gold Opportunity Plan, UC covers the full tuition and fees for California students from households with incomes of less than $80,000. It uses a significant amount of its own budget to cover the gaps in Pell funding.

If Pell Grants covered a greater share of tuition for its neediest students, UC could expand its support to other needy students, including undocumented students and those who are just above the income threshold to qualify for federal assistance.

“A lot of my friends have had to take quarters off, drop out or take on additional jobs to take care of their families and their parents. All of this is pushing some of UC’s most vulnerable students out of higher education,” said Arasasingham.

“If students are able to have that increased support it will make a world of difference.”

Powering an educated, upwardly-mobile workforce

Advocates say stronger Pell funding is critical to making college — and a UC education — accessible to students from all backgrounds and walks of life. Investing in the program, they say, has benefits that go far beyond the individual students who receive it.

Recent graduates now often delay buying a home, starting a business, pursuing graduate school or doing other things that benefit the economy because they are too strapped by student loans. Easing that burden would boost economic growth.

At UC, students who receive Pell Grants graduate at high rates, similarly to their more affluent classmates. Many go into fields that help lift others out of poverty, and they also serve as role models to inspire family and community members to strive for college.

They move up the income ladder, as well: Within five years of graduating, the median income of Pell Grant recipients eclipses that of their families when they entered college.

Among UC alumni who came from households in the bottom 20 percent of income, one in three has gone on to be in the top 20 percent.

“This is our next generation of doctors, of teachers, of health workers, of people who are willing to help others,” Serratos said. “By investing in Pell, we’re investing in our own future.”

Join the campaign to Double the Pell and support UC’s efforts to make college more affordable for all students.