Julia Busiek, UC Newsroom

Vanessa Mora Molina learned about California’s doctor shortage the hard way.

As a kid growing up in Fowler, a farming town of seven thousand people in California’s San Joaquin Valley, she was prone to strep throat. A quick trip to the doctor and a prescription for antibiotics could have had her feeling better in a day or two. But in Fowler, there wasn’t really such a thing as a “quick trip to the doctor”: Mora sometimes waited weeks to get an appointment.

“Sometimes we’d go to the emergency room just so we could be seen by a doctor, and even that could entail an eight-hour wait,” Mora said. Her parents were reluctant to ask for time off from their jobs at farm laborers for fear of getting fired.

Determined to make life easier for families like hers, Mora started the long journey to a career in medicine. She enrolled in UC San Francisco’s San Joaquin Valley Program in Medical Education in 2020.

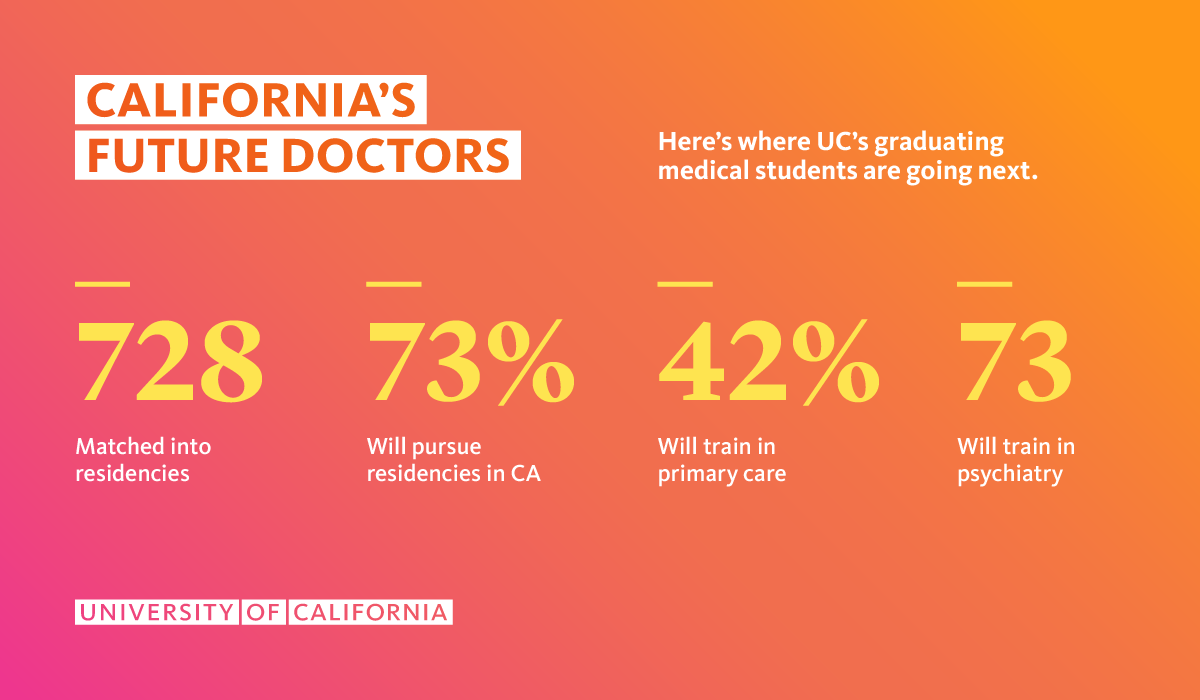

This June, she will be one of more than 700 medical students earning their M.D. from across UC’s six medical schools. The vast majority of these newly minted doctors — 73 percent — will stay in California for their residency training.

And like Mora, many of them have received specialized classwork and training through the UC PRIME program, preparing them to provide care to medically underserved people across the state. In mid-March, UC’s fourth-year medical students found out where they’ll complete the next phase of their education: Of the 728 students who will graduate from medical schools across UC this year, 94 percent of them were admitted to residencies, including Mora, who will continue her training in general surgery at UCLA this fall.

How UC PRIME is meeting California’s health care needs

UC PRIME exists to meet the needs of communities like the San Joaquin Valley, where doctors are too few and far between.

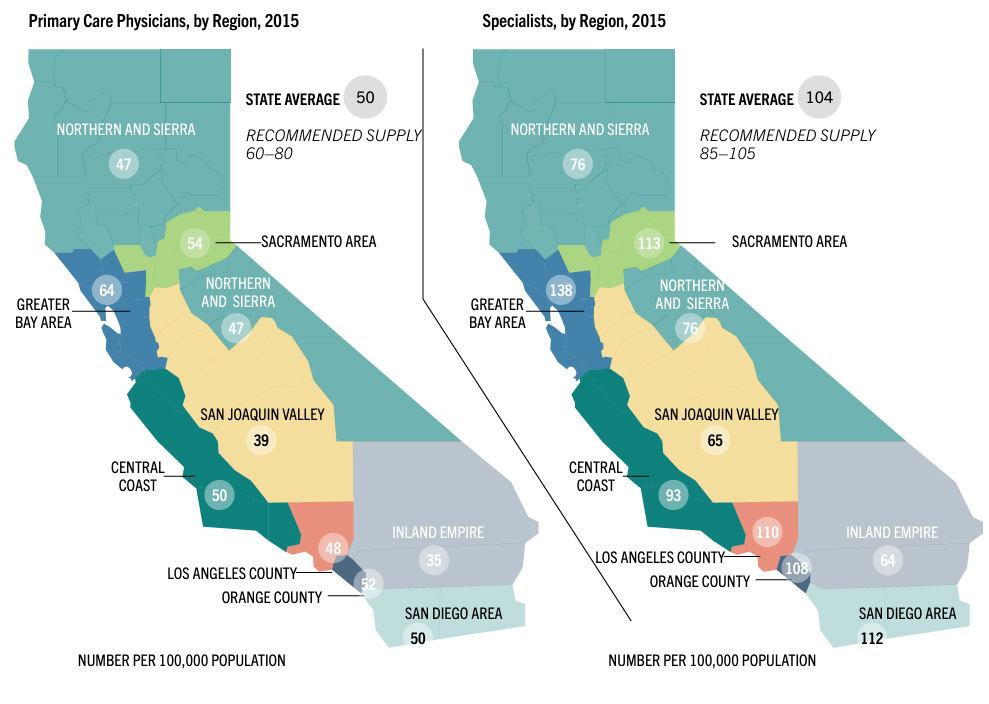

The region has just 39 primary care providers per 100,000 people, compared to the more affluent Bay Area, which has 64 primary care providers for every 100,000 people. (That’s the highest rate in the state, yet still just barely above the minimum recommended threshold of 60 providers per 100,000 people, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.)

And for too many people in California’s “health care deserts,” getting an appointment is just the start of the struggle. Many doctors don’t speak their patients’ languages, or know enough about how the community’s culture and norms contribute to their patients’ health and well-being.

“We don’t just need more doctors in this community. We need doctors who understand it,” said Dr. Katherine Flores, a family medicine physician who supervised Mora at a clinic in Fresno. “We need students who come from the Valley, who understand the culture of the Valley, who understand the challenges of poverty and the challenges of the community.”

Disparities cost Californians their health

But for too many Californians, that kind of doctor is hard to find. Today, for instance, Latinos make up 39 percent of the state’s population, but just six percent of its physicians. This discrepancy has real consequences, and they’ve been clear for decades: as far back as 2001, researchers found that one in five Spanish speaking U.S. residents delayed or refused medical care they needed because of language barriers.

A 2002 study found that when given a choice, people of color are likelier to pick doctors with whom they share a racial or ethnic background, and a 1999 report found that patients of color are more satisfied with the care they receive from doctors of color compared to white doctors. And several studies published in the mid-1990s found that doctors of color are more likely than their white peers to treat patients of color, unhoused patients, and patients that are sicker.

The University of California launched UC PRIME in 2004 expressly to chip away at these disparities. More than 800 doctors have come out of UC PRIME equipped to take on the state’s most daunting and complex health care challenges. For many of these doctors, their own life experiences served as motivation to grind through medical school, and as information to provide the best possible care for their patients.

Motivated by experience

That’s the case for Javier Rodriguez, who’s graduating from the UC Davis School of Medicine in May and will begin his residency in adult neurology at UC San Francisco this summer. He was an active, healthy 13-year-old growing up in Ceres, a small town in the San Joaquin Valley, when he experienced what he calls “an event that changed my life’s trajectory”: One afternoon, he felt a sharp pain in his neck. Within 24 hours, the left side of his body was paralyzed from the neck down.

Doctors eventually diagnosed Rodriguez with idiopathic transverse myelitis, an unexplained inflammation of the spinal cord. He spent a month in the ICU, and three months in inpatient recovery relearning how to walk.

This would have been a shocking, scary and destabilizing event for any family. For the Rodriguezes, it was made worse by the fact that the nearest hospitals equipped to handle his case were in Oakland, a two-hour drive from their home in Ceres. The family had to split up: his dad kept up the family business and cared for his brother back home, while his mom moved into his hospital room, staying by his side for the four months of treatment and recovery.

Before his hospitalization, “All I wanted to do in life was play soccer,” Rodriguez says. “But I came out the other side interested in what makes the body work, how it’s all wired, and how something like this could happen.”

That curiosity and perspective has motivated Rodriguez ever since. A first-generation college student, he majored in Neurobiology, Physiology and Behavior at UC Davis. He got into the UC Davis School of Medicine, where he enrolled in REACH, a UC PRIME program for students interested in gaining knowledge and expertise in caring for communities in California’s Central Valley.

Javier Rodriguez graduates from the UC Davis School of Medicine this spring.

His training sent him to communities and clinics across the region, providing care to people from diverse backgrounds and cultures. He did stints in a clinic providing preventative screenings and wound care for people experiencing homelessness and vaccinated people against COVID-19 in Visalia. At a flea market in Modesto, he fielded questions from shoppers about managing their hypertension and reading their lab results.

He'll bring lessons from those encounters, and from his own experiences as a patient, to his next stage of training at UC San Francisco.

"Having a background in medically underserved areas has taught me the importance of recognizing a patient's cultural and personal history. However, understanding one community doesn't mean you understand another," he explains. "The complexities of both human culture and medical science are immense, making it difficult to ever say, 'Okay, I fully understand what's happening.' The more you learn about medicine or someone’s life, the more you realize how much there is yet to know."