Nicole Freeling, UC Newsroom

Federal financial aid played a big role in making it possible for Rakia White, a low-income, first-generation college student, to access a UC Berkeley education. But it’s hardly been easy going.

“I was doing everything I could, and it still wasn’t enough,” the Marin Community College transfer student told an audience of more than 100 at a Feb. 23 congressional briefing organized by the UC Student Association.

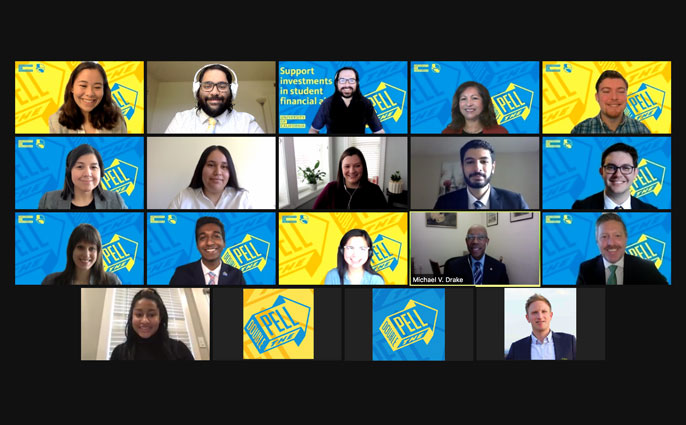

UC students have joined with their peers from across the country in a concerted effort to advocate for an increase in federal financial aid for low-income students. The campaign is calling on Congress to reinvest in the Pell Grant program, the primary source of federal aid for low-income college students.

Courtesy photo

White described how, as a student at Marin College, she worked up to 50 hours a week in three jobs — as a nanny, receptionist and desk manager — and still struggled to find stable housing. At one point, she said, she was couch surfing and staying at school late into the night to access free Wi-Fi.

“I felt like I couldn’t engage in my coursework as I wanted to because of all the work I was taking on,” she said. More robust federal financial aid would be a game-changer for students like White who have “lived on the edge of hopelessness and uncertainty.”

UC leaders have joined with students in calling on Congress to double the maximum Pell Grant award, from about $6,400 today to $13,000 within the next three fiscal years.

Pell Grants, which do not need to be paid back, are available to students from extremely low-income families, generally those with incomes of less than $50,000 a year.

The grants support 7 million students a year, including more than 78,000 UC undergraduates. Since the program was started in 1965, Pell Grants have helped countless students attain a college degree and the economic mobility that comes with it.

Yet the purchasing power of a Pell Grant has declined dramatically over the past several decades, and now covers less than a third of college costs. In 1980, these grants covered nearly 80 percent of the costs to enroll at a public, four-year university. Today, it is just 28 percent.

As a result, students often take on more debt, work longer hours, and sometimes resort to skipping meals to make ends meet. Like Rakia White, some wind up sleeping in their cars or couch surfing with friends to get by.

Now, with the pandemic adding to their financial stress, these vulnerable students are at risk of dropping out, threatening the substantial time and investment that has already been made in their education.

“Millions of students face very difficult choices about how to support themselves and their families,” said UC President Dr. Michael Drake, who joined student leaders in addressing lawmakers at Tuesday’s briefing.

“Doubling the Pell would give them much-needed relief. Together, we can demonstrate our commitment to these students and their abilities with the opportunity to attain the American Dream.”

Credit: University of California

A lynchpin for equity

UC students are drawing attention to the need for more aid by sharing stories in the press and on social media, using the hashtag #DoublePell.

They are also meeting with representatives of influential lawmakers, including California Congressional representatives, members of the Biden administration, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, and other leaders.

“I’m a little nervous, but I’m excited to advocate for this important program,” said UC Santa Barbara undergraduate Dalila Lara, a double major in global studies and biological anthropology.

Courtesy photo

The daughter of factory workers who emigrated from Mexico to give their kids a shot at education and opportunity, Lara said the Pell Grant has helped her achieve her dream of pursuing graduate school and a career in research and academia, and has opened up opportunities she had never thought possible, such as doing field research on Santa Cruz Island and in Panama with the Smithsonian Institute.

Yet, even with the Pell Grant and other aid, she has had to work multiple jobs to cover food and living expenses. “Better aid would let students like me shift our focus from making ends meet to be able to explore more opportunities and excel in our academic careers,” she told lawmakers.

Advocates say the Pell Grant is a program with broad public support that has helped create a more educated and upwardly mobile workforce.

It has been especially instrumental in enabling students of color, first-generation college students, veterans and student-parents to achieve higher education.

At UC, where 35 percent of undergraduates receive Pell funding, the program has proven transformative for students’ social mobility. Within five years of graduating, the median income of Pell students exceeds that of their families when they first enrolled at UC. And more than one in three of these very low-income students see their incomes rise, after graduation, to be among the top 20 percent.

“Doubling the Pell is a student necessity. The Pell Grant has shrunk in value, impact and its ability to enable students to access the opportunity they deserve,” said Joshua Lewis, chair of UCSA's government relations committee, and a political science major at UC Berkeley.

“Every day the Pell Grant is devalued is a day a student is denied an education,” he said.

Taking aim at student debt and food insecurity

Courtesy photo

Nationally, one in three college students struggle to cover the cost of food, housing and other basics, a proportion that is likely higher among Pell Grant recipients.

Increasing the Pell Grant would help students meet those basic needs, and it would also help UC extend financial aid to additional deserving students, including those who are undocumented or are just above the threshold to qualify for the assistance.

Increasing the Pell Grant would also ease the student loan crisis by enabling low-income students to take on less debt to graduate, UC leaders say.

“Today, 80 percent of Pell Grant recipients take out loans and they are more than two times as likely to borrow as their more affluent classmates,” said Shawn Brick, UC director of student financial support. “UC students graduate with less debt than the national average, but the gap between low-income students and others is concerning.”

Doubling the Pell would enable UC to cover enough of students’ total cost of attendance, including meals and living expenses, to significantly reduce that debt burden.

“By restoring the relative buying power of the Pell Grant, there exists an opportunity to make a lasting, permanent step to a debt-free college education,” UCSA’s Lewis said. “Doubling the Pell is the responsibility of our federal government to restore equitable access to higher education.”