Jess Berthold, UC San Francisco

A UC San Francisco-developed tool to detect early signs of literacy weaknesses that could lead to dyslexia got a boost in the California governor’s recent budget proposal, and could be in widespread use in the state’s public schools by 2023.

Dyslexia is a brain-based learning challenge that affects about 15 percent of the population and is unrelated to intelligence, according to the International Dyslexia Association. Children with dyslexia have trouble learning to read and write, and can fall behind if the condition is unaddressed.

UCSF’s free digital assessment, which has been piloted with 2,000 students at dozens of California schools to date, is meant to spot pre-reading challenges in kindergarten or first grade, so educators can intervene before dyslexia is typically diagnosed, said Marilu Gorno Tempini, M.D., Ph.D., Charles Schwab Distinguished Professor in Dyslexia and Neurodevelopment, and co-director of the UCSF Dyslexia Center and the UCSF-UCB Schwab Dyslexia and Cognitive Diversity Center.

“We don’t usually diagnose dyslexia in kindergarten — kids are not expected to read fluently yet,” Gorno Tempini said. “But we know there are risk factors and the hope is that if we address those factors earlier on, the kids will not develop the difficulties with written language associated with dyslexia.”

“By the time dyslexia is recognized in third or fourth grade, kids have suffered through feeling incapable or being bullied for years” she added. “In a worst-case scenario, these kids fall further behind and eventually drop out. So we are really creating a prevention tool here.”

Governor Gavin Newsom, who struggled with dyslexia as a child, allocated $10 million to UCSF for dyslexia research in his January budget proposal. Lawmakers will debate the 2022-23 budget over the next few months, with a final budget plan due in June.

The UCSF Dyslexia Center received $15.2 million in the current year’s state budget, and $3.5 million from the 2019-20 state budget. Last year, a budget trailer bill allocated $4 million for dyslexia early intervention in the school system last year, as well.

Neuroscience-based approach

UCSF’s assessment tool, called Multitudes, is unique because it is based in the latest neuroscience research and designed to be paired with interventions, said Gorno Tempini, who is affiliated with the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences.

“Dyslexia has been addressed mainly as an academic issue and not a neurological/health one, and research usually goes through schools of education or psychology without a comprehensive brain health approach to the issue,” Gorno Tempini said. “Here, we are combining the brain and education sciences, the imaging, the biology and the technology to really understand the strengths and weaknesses of dyslexia and bring it back to empower families and schools and children.”

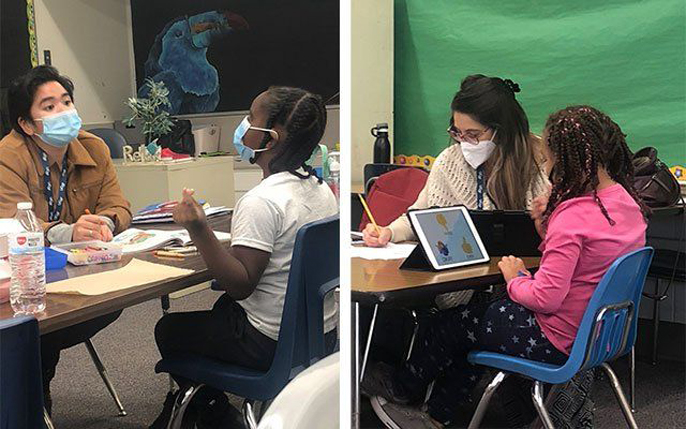

Though administered by proctors on iPad currently, Multitudes will ultimately be web-based, administered by educators and take about 20 minutes. Some elements of the assessment are adapted from partner universities in other states, and UCSF is validating them for the California school population — essentially validating and revising the assessment in real time, said Phaedra Bell, Ph.D., a UCSF program manager and director of school partnerships of the Multitudes project.

“This isn’t a tool that is ‘done’,” said Bell. “It will continue to be perfected and the data we collect will continue to inform it.”

Commitment to diversity and collaboration

The Multitudes project team is prioritizing equity in the creation and use of its tool, noted Michelle Porche, Ed.D., associate director of community outreach for the UCSF-UC Berkeley Schwab Dyslexia and Cognitive Diversity Center.

The 30-plus schools across California that are piloting Multitudes were chosen to reflect the state’s demographics, and the scientists, clinicians, teachers, designers and software engineers who are working on the tool are from diverse communities.

“We are building inclusive partnerships with schools and communities, so that we can recruit participants for our studies that reflect the racial, ethnic and linguistic diversity of the state,” said Porche. “The study of dyslexia has been limited by a lack of racial, ethnic, and linguistic representation, but we are increasingly intentional about addressing structural racism that creates barriers to success for students of color in California.”

Initial research for the UCSF assessment was conducted at specialty schools for dyslexia, such as the Charles Armstrong and Chartwell Schools, and funded by Charles Schwab and other philanthropists, noted Christa Watson Pereira, Psy.D., UCSF assistant professor of neurology and advisor to the Multitudes project.

“These independent schools, and the families and students who go there, gave us the opportunity to have a cohort of 400 children with dyslexia and other learning challenges who volunteered hours of their time to be tested and scanned with MRIs, and donated their DNA,” said Watson Pereira. “From these children we gathered the evidence to make the tool that we are now scaling to public schools.”

The English version of Multitudes was piloted in fall 2021; the Spanish version will be piloted in spring 2022 and the Mandarin version in fall 2022. The goal is to reach 10,000 kids by the end of 2022, and to have the free tool in widespread use for California schoolchildren in 2023, Bell said.

From assessment to intervention

At the same time Multitudes is being validated and refined, UCSF researchers are working with the schools of education at University of California, Berkeley and University of California, Los Angeles to curate best-practice materials, curriculum and interventions for educators to use when reading challenges are detected. The Sacramento County Office of Education also is working closely with UCSF on the best way to train teachers across the state in early reading instruction.

Currently, schools often use a single approach for reading issues that may not work for all students, Gorno Tempini said. For example, a school may use specific “dyslexia fonts” that are presumed to make reading easier for students who struggle, yet these fonts may not help children whose language issues stem from auditory problems.

“The idea is to have multiple interventions available at every school that can be tailored to the strengths and weaknesses of each student, rather than each school having a different approach,” Gorno Tempini said. “Different brains learn differently, and from a neurological point of view, precision education makes the same sense as precision medicine.”

Marilu Gorno Tempini, M.D., Ph.D., co-director of the UCSF Dyslexia Center.