Anne Kavanagh, UCSF Magazine

It sailed in stealthily, like the fog.

Carried by the hordes eager to grab gold, tuberculosis began a frightening, infectious march through San Francisco in the mid-1800s. Known then as consumption, given the way it appeared to consume the body, or as white plague, given the ghostly pallor of its victims, the disease found a receptive new home in the wild West Coast city.

At the time, no one knew that tuberculosis spread through the air via microscopic droplets and that sneezing or coughing transported a bacterium capable of attacking the lungs of those who inhaled it. Many of the settlers lived crowded together in damp cellars or flimsy tents, amid a toxic mixture of diseases: cholera, diphtheria, leprosy, scurvy, smallpox, malaria. Illness and malnutrition weakened the immigrants’ immune systems, allowing infections to thrive.

Consumption had already cut a wide swath of death down the East Coast earlier in the century. Effective treatment for the ancient disease remained elusive, so stymied physicians turned to natural solutions. Some recommended rest, others exercise; some a warm climate, others cold. A South Carolina surgeon whose wife was ill sought the mild winters of California — and also its gold.

UC San Francisco’s 150-year battle against tuberculosis, and other infectious diseases, was about to begin.

Joining forces

That surgeon, Hugh Toland, M.D., and his wife, Mary, reached Calaveras County in 1852. A few days after their arrival, Mary died and Toland’s subsequent search for gold proved fruitless. Starting over, he moved to San Francisco and, in 1864, launched a medical school that would bloom into UCSF.

One year later, a French military doctor, Jean Antoine Villemin, M.D., demonstrated that consumption could be transmitted from humans to animals, revealing its contagious nature. In a win for the disease, the scientific community largely ignored this key discovery.

San Francisco, meanwhile, took aim at the city’s atrocious health conditions with the construction in 1872 of a city and county hospital — which evolved into San Francisco General Hospital (SFGH); its primary mission was to care for patients with infectious diseases. “Nobody else wanted them,” explains professor emeritus John Murray, M.D., a pioneer in the field of modern pulmonary medicine, who arrived at SFGH in 1966.

UCSF’s medical school struck an agreement to use SFGH as its clinical facility in 1873, a partnership that marked the start of a one-two punch against the scourge. It also began what would grow into a rich training arena, exposing students to patients from many cultures and myriad conditions. Even so, consumption continued to steamroll across San Francisco: Municipal reports in 1880 noted that tuberculosis mortality had climbed to 690 that year, from 223 in 1865.

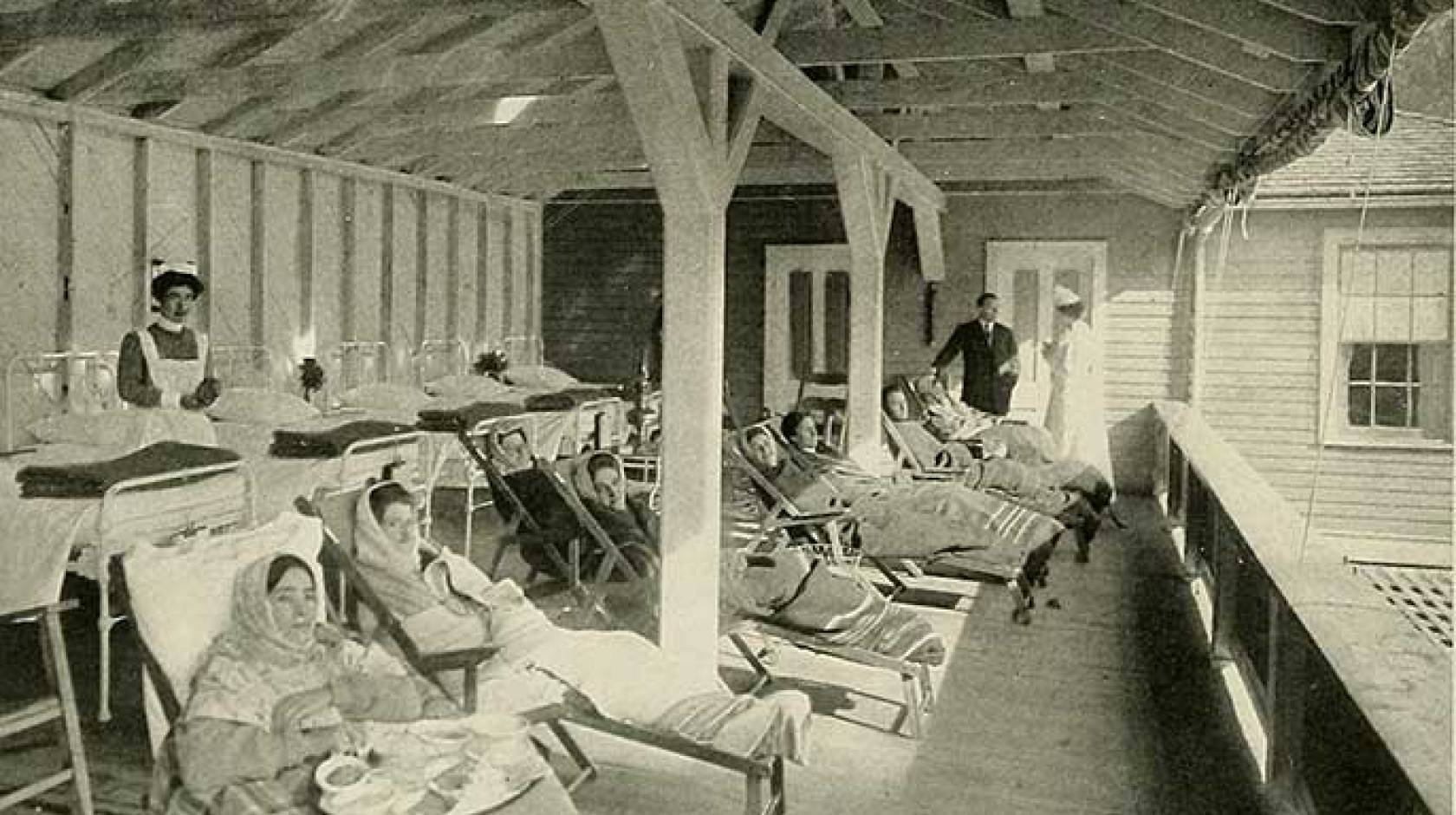

Around this time, sanatoriums began gaining popularity in the United States as a way to offer patients rest and fresh air. “There was no other treatment,” explains Murray. “Zero.” Isolating consumptives in sanatoriums, however, did help prevent contagion.

A blow, but no knockout

Courtesy of National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

One of the first cracks in TB’s armor came in 1882 when a scientist identified Mycobacterium tuberculosis as the bacterium that causes the disease. In quick response, UCSF physicians began segregating patients with tuberculosis from other patients. The city also mobilized by enacting an ordinance prohibiting public spitting and another requiring registration of all TB patients, the latter a trailblazing step in public health.

Another chink in the disease’s armor occurred with the 1895 discovery of X-rays, which allowed doctors to see abnormalities in the chest. “The news about X-rays spread like wildfire,” says Murray. By 1905, physicians could precisely diagnose tuberculosis through primitive chest radiographs and by identifying tubercle bacilli in a patient’s sputum.

But a dozen years after that promising advance debuted, the bubonic plague struck San Francisco. After workers at SFGH discovered that plague-infected rats were spreading the disease within the hospital, the city burned it to the ground. In a boost for patients with tuberculosis, the new SFGH constructed in 1915 featured nine TB wards that maximized sunshine and fresh air. Newspapers from as far away as New York trumpeted the facility as the finest of its kind.

And still, with no effective treatment, the disease’s deadly march continued. In 1922, half of the TB patients admitted to SFGH died there. (A vaccine against TB was introduced in Europe in 1921, but its efficacy rates varied enormously and it was never widely adopted in the United States.)

Finally, in the 1930s, the number of tuberculosis cases in San Francisco began to decline, thanks to improving economic conditions; to the removal of contagious patients from the community; and to the availability of good care, good nutrition, and rest. TB’s incidence dropped by almost 25 percent from 1905 to 1933.

For UCSF’s trainees on the front lines of care, however, the progress posed a risk. As more young people reached adulthood without any exposure to the disease, one-third of medical and nursing students contracted TB in 1933 during their rotations at SFGH. By the mid-1950s, an average of 10 percent of medical students and young doctors had contracted the disease, prompting mandatory screening via skin tests and chest X-rays.

Triple threat: Drugs spur downfall

In 1944, scientists isolated Streptomyces griseus, which led to the production of streptomycin, the first antibiotic effective against tuberculosis. At exactly the same time, a second antituberculosis drug, paraaminosalicyclic acid (PAS), was discovered, but its acceptance was much slower than streptomycin’s.

A tough microorganism, M. tuberculosis quickly developed resistance to both streptomycin and PAS. But in 1952, scientists discovered a “miracle” drug, isoniazid, or INH. They soon learned that combining the three drugs — a triple therapy — could regularly cure the disease. The regimen “changed TB from that moment on,” says Murray.

Death rates dropped rapidly and dramatically. Sanatoriums around the nation shut down, and the TB wards at SFGH began emptying out.

With the success of these and subsequent tuberculosis medications in the 1960s and ’70s, the locus of treatment shifted from the hospital to the community. A San Francisco physician, Francis Curry, M.D., established satellite clinics throughout areas of the city with a high incidence of TB and set convenient clinic hours, giving rise to a compassionate, patient-centered approach to combating the disease.

War and AIDS spark resurgence

Then a conflict raging far from San Francisco shook the city’s relative calm in the late 1970s — war. An influx of Southeast Asian refugees, many of whom had been living in squalid refugee camps under conditions likely to foster tuberculosis, started arriving in the city.

TB rates began climbing again, peaking in 1979. In response, the Department of Public Health’s Tuberculosis Control Program hired a handful of people from the Southeast Asian community, including a medical student from Cambodia and a nurse from Laos, to work in the TB clinic at SFGH. “It was a very wise move,” says Philip Hopewell, M.D., a UCSF professor of medicine and a leading tuberculosis expert based at SFGH since 1973. “It met a lot of our language needs and gave us the cultural understanding to help people effectively.”

In 1980, UCSF contracted with the city to provide clinical care for patients through the TB Control Program, which meant UCSF doctors would now be involved not just in care, but also in prevention and other public health efforts. “The concept was to merge an academic institution with a good, sound public health program to the benefit of both,” says Hopewell, who is also a UCSF resident alumnus.

The timing proved fortuitous; in 1982, AIDS began to run riot through San Francisco. TB and HIV are a lethal mix; tuberculosis is the leading cause of death in HIV-infected individuals worldwide, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The TB program brought a solid foundation in community-based, patient-centered care to confronting this new threat. The TB and AIDS programs pioneered at SFGH worked closely together, successfully partnering with AIDS groups to develop screening and prevention programs, says Hopewell. San Francisco also had an advantage: the population most heavily affected by HIV was middle-class, gay, white men. Unlike many immigrants, most did not live under conditions that fostered TB and thus they remained relatively untouched.

So while TB rates did climb again in the city, peaking in 1993, the surge was smaller than in other parts of the country hit hard by AIDS. With the introduction of sophisticated antiretroviral therapies in the mid- to late 1990s, the number of HIV-positive San Franciscans with TB fell to near zero.

Rise of research and training

UCSF’s partnership with the TB Control Program also created an excellent venue for training. Students, residents, and fellows who rotated through the TB clinic could gain rich experience both with the disease and with public health measures. A number have since gone on to leadership careers in the field and in public health, including Julie Gerberding, M.D., MPH, former director of the CDC; Eric Goosby, M.D., former U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator; Peter Small, M.D., head of the tuberculosis delivery program at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; Charles Daley, M.D., chair of the World Health Organization (WHO) TB advisory committee; and Richard Chaisson, M.D., director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Tuberculosis Research.

The partnership enriched the research effort as well. Since the early 1980s, for example, UCSF faculty have been studying the epidemiology of tuberculosis, a daunting task. Most infected people never develop the disease — their immune system fights off the bacterium. Only about 10 percent develop active TB, but that can happen at any point during someone’s life. “It’s hard to connect the person with the source of the infection that may have been contracted 20 years earlier,” Hopewell notes. But in the early 1990s, researchers began to use a sophisticated DNA-fingerprinting technique, plus contact-investigation strategies, that harvested new knowledge on how tuberculosis spreads and progresses from latent to active disease.

Despite the progress — rates fell to an all-time low of 98 cases in 2010 — San Francisco still has one of the highest TB rates in the country. Among the reasons is a factor that hearkens back to the Gold Rush: The city remains an international magnet. Many immigrants are infected in their home countries but don’t develop the disease until years later. San Francisco’s large marginally housed population also contributes to its high rate of TB.

Going global

In other parts of the world, tuberculosis continues to rage. According to the WHO, approximately one-third of the world’s population is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In 2012, the disease sickened nearly 9 million people and killed 1.3 million.

This stark global situation caught the attention of UCSF years ago. In 1994, UCSF opened the Curry International Tuberculosis Center — named in honor of Francis Curry — to develop and share state-of-the-art resources and perform research to eradicate TB.

The center is partnering with a number of countries to develop programs based on seminal work by Hopewell and other experts — a regimen known as the International Standards for Tuberculosis Care; it was developed, as a tool to help countries better manage the disease, by a consortium that included WHO.

Under Hopewell’s leadership, UCSF researchers in Tanzania and Zimbabwe are studying multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and examining the transmission of the organism between people and animals. In Uganda, they are developing better diagnostic techniques. In India and Indonesia, investigators are trying to unite private doctors with public health efforts.

“We’re taking what we learned in San Francisco,” says Hopewell, “and applying it to the world.”