Victoria Clayton, UC Irvine

With sleep such a basic aspect of life, one might assume that scientists have investigated every angle of slumber and can tell us what we need to know about why we snooze and what it does for the human body.

Unfortunately, that’s not true — at least not yet, says UC Irvine sleep researcher Sara Mednick, professor of cognitive sciences. She says sleep is still very much a “black box.” “We sleep for about a third of our lives, but so far it has received very little attention from basic research and medicine,” explains Mednick, director of UCI’s Sleep and Cognition Lab.

It wasn’t until the late 1980s that sleep research gained a foothold and scientific legitimacy; the American Medical Association waited until 1995 to deem sleep medicine a practice specialty. By 2005, researchers had not only identified and clearly delineated a significant number of dozing disorders but also established that many of them were highly prevalent. The pace of discovery has gone warp-speed since then, tripling the number of peer-reviewed sleep journals. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic was brutal on slumber — a recent study found that up to 40 percent of the population suffered sleep problems during the crisis. All this adds up to a healthy fascination by researchers — and the public — with sleep.

At UCI, a number of scientists and doctors across disciplines are joining Mednick in taking shut-eye seriously. They’re uncovering a plethora of new information about how sleep is related to mental and physical well-being, as well as health inequities.

Wake and sleep are fundamentally controlled by a natural process in the body that hinges on our circadian rhythms, an innate timekeeping system that’s sensitive to light and dark cues and regulates our bodies’ physiological and biological activities during each 24-hour day. Researchers well know that smooth operation of this process is necessary for the very survival of all living organisms. Studies have demonstrated that unremitting sleep deprivation can even lead to death.

Yet the latest statistics from the National Institutes of Health indicate that over 20 percent of American adults report some sleep problems. In fact, approximately 50 million to 70 million adults suffer from a sleep disorder. The American Academy of Pediatrics estimates that 14 percent of children and adolescents also battle sleep issues.

What happens biologically when we sleep poorly? There’s increased activity in our central stress response system, called the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, as well as the sympathetic nervous system. This means higher levels of stress hormones, more insulin resistance and more inflammation, among other problems. And researchers have uncovered a variety of intertwining physical and mental consequences — everything from memory impairment and difficulty learning to an increased risk of hypertension, high cholesterol, cardiovascular disease, weight-related issues, Type 2 diabetes and certain kinds of cancer.

No Rest for UCI Scientists

“We know that a good night of sleep makes you feel better emotionally and increases your memory and physical performance,” Mednick says. “My lab investigates the mechanisms in the brain and body that contribute to those improvements. We also examine what happens to emotions, performance and memory when you don’t get sufficient sleep. Specifically, we’re exploring how sleep and cognition are affected by aging and the menstrual cycle — but also opioid addiction, poverty and homelessness.”

Sara Mednick (right), director of UC Irvine’s Sleep and Cognition Lab, with a fellow researcher

Mednick’s previous research has shown the positive benefits of rest on memory and cognition. In one study, she found that a 60- to 90-minute nap could impact certain learning tasks as much as a full night’s sleep. Now a major focus of her lab is what happens with sleep and cognition over the course of women’s menstrual cycles. Specifically, researchers want to know if sleep — and thus intellectual performance — changes.

“We know that there are four distinct hormonal phases of a menstrual cycle, but there’s not enough research on women’s health in general and certainly not enough on sleep,” says Katharine Simon, a former assistant researcher in the Sleep and Cognition Lab and a licensed clinical psychologist.

Mednick’s lab, along with colleagues from Stanford University, received a grant in 2019 from the NIH to further understand each distinct phase of the menstrual cycle, what sleep and memory look like in each of those phases, and how sleep supports long-term memory and working memory in women.

The preliminary findings have been surprising, Simon says: “There’s this kind of dogma that says women’s hormones are constantly influencing their behaviors and impacting their memory, but right now at least, our preliminary data is not showing major changes across the menstrual cycle in terms of cognition and sleep.” This, she says, suggests that women are thinking just fine no matter the time of the month.

Simon notes that researchers have found sleep to be especially critical for forming certain types of memories — those that are hippocampal-dependent, i.e., stories about your life.

“Sleep is important to those memories where you think of a who, what, where, when and why — like your birthday last year or a fun day out that you had with a friend,” Simon says. “The memory of that experience – all the details, the people and the feelings — is what’s called an episodic memory.” For this reason, another line of inquiry for the Sleep and Cognition Lab is how sleep might impact diseases like Alzheimer’s and dementia.

Sara Mednick, director of UCI’s Sleep and Cognition Lab

Simon recently accepted a joint appointment as an assistant professor in the UCI School of Medicine’s Department of Pediatrics and with Children’s Hospital of Orange County. She says her new research will focus on sleep across development in pediatric patient populations. Her ongoing investigations include the trajectories of mood, sleep and memory in children with and without depression, as well as evaluating adolescents undergoing treatment for sleep apnea — an abnormal breathing condition — to support healthy development.

“There aren’t very many people who are really studying pediatric sleep and trying to figure it out,” Simon says. “So that will be the goal of my lab.”

Other researchers at UCI have explored adult behavioral health and sleep, however. Amal Alachkar and colleagues in the School of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences and in the Donald Bren School of Information & Computer Sciences have explored the hidden link between circadian rhythm disorders – characterized by sleep disruption – and mental health challenges. Their examination of peer-reviewed literature, published last year in the journal Translational Psychiatry, found that sleep disruption is connected with all the most prevalent mental health disorders, including illnesses as varied as anxiety, autism, schizophrenia and Tourette syndrome. The researchers posit that exploring the molecular foundation of disturbed sleep and circadian rhythm disorders could be key to unlocking more effective therapies for a host of mental illnesses.

At the very least, Mednick says, there needs to be a much deeper appreciation of sleep. “I hope to bring the importance of sleep for human functioning out of the lab and into the real world,” she says. “In particular, the acknowledgment of disparities in many health areas needs to extend to sleep, which is a basic need and is causally related to chronic disease and mental health disorders.”

Exploring Sleep in Communities of Color

Karen Lincoln, professor of environmental and occupational health and director of UCI’s Center for Environmental Health Disparities Research, also counts herself among campus researchers obsessed with sleep. She explores health disparities and stressors, including in the context of sleep.

“What we know from epidemiological data is that, on average, Black Americans have the poorest sleep quality in the country,” Lincoln says.

Sleep tends to be socially patterned. People who do shift work, log long work hours or work multiple jobs often have poor, disrupted and irregular sleep patterns. Those with lower-paying jobs more often have less control and flexibility in their schedules. Social patterns of neighborhoods — including noise, light, traffic, air pollution, crime and discrimination — also impact sleep.

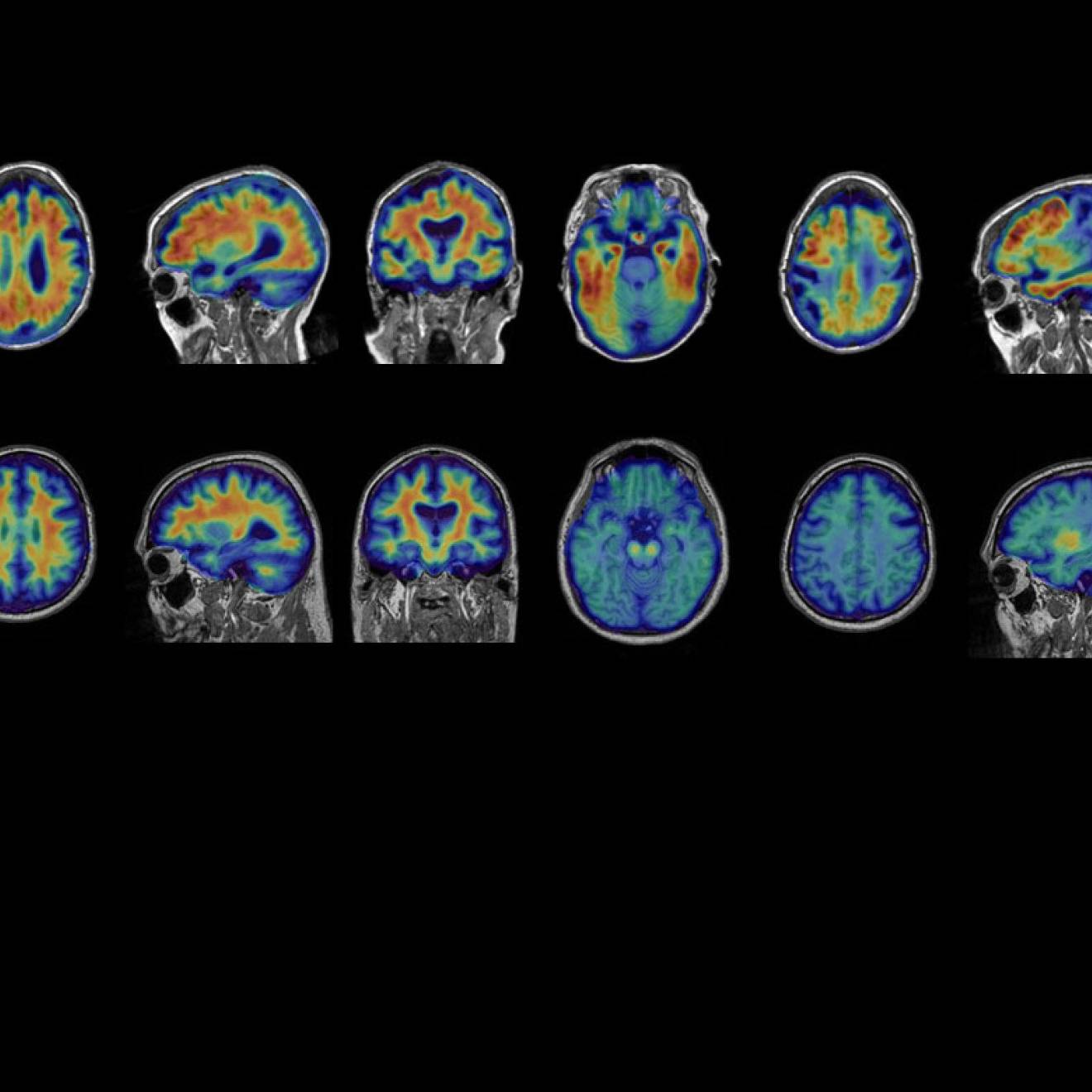

Lincoln has used high-powered neural imaging to gain a better understanding of sleep’s role in a brain clearance process thought to be linked to Alzheimer’s. There are higher rates of the disease in Black communities, and researchers believe sleep disturbance plays a role.

But that’s not the end of the story, Lincoln says. “Unfortunately, the stories that we get are often that Black people have higher rates of this or higher rates of that — and that’s it,” she says. The problem is that Black Americans are being treated monolithically. Lincoln pushes for more nuance in her research. Some of her studies have parsed African American and Black Caribbean experiences, for example.

“There are a lot of similarities between these populations, but there are also a lot of differences,” she says. “My work centers on exploring heterogeneity in the Black American population, and we don’t often do that in research. The solutions that we’re looking for with respect to sleep and other health interventions already exist within Black Americans themselves, but we’re often not asking the right questions.” Lincoln says researchers need to look more closely at Black people who are doing very well — living long and healthy lives.

Sunmin Lee, a professor and social epidemiologist in the School of Medicine, and Brittany Morey, assistant professor of health, society and behavior, are looking at the social and environmental stressors leading to poor sleep — but also the healthy sleepers – in Asian populations. They’re collaborating on the UCI Dreams Project, an NIH-funded study.

Morey notes that Asian Americans suffer from the opposite of what Lincoln describes; they’ve been saddled with a “model minority myth” that has existed basically since the 1960s, suggesting that Asian Americans are all thriving. Meanwhile, researchers know that’s not accurate. Sleep research suggests that Asian Americans have shorter sleep duration, on average, than the general population, and they’re more likely to experience sleep apnea even if they’re not overweight or obese. Some research has suggested that facial bone structure could play a part. In their research, Lee and Morey are attempting to tease out data to tell the sleep health stories of Korean, Chinese and Vietnamese Americans.

“We’re finding that language barriers and acculturating to a new country can generate stress, which may affect sleep,” Lee says. “We’re also hearing more and more about anti-Asian discrimination and ‘Asian hate.’ All of this can impact sleep.”

On the other hand, Morey notes, most immigrants are strong and inherently resilient. “We think that sometimes there’s a selection effect,” she explains. “People who are able to immigrate, to uproot their whole lives and move to a foreign country, are unique.” Does this resilience impact sleep and health? That’s one of the questions the researchers hope to shed light on at the end of their five-year study. Says Lee: “Our aim is to design a tailored intervention for these groups to enhance positive factors and prevent negative factors.”

The Next Frontier

Sleep researchers agree that we’ve just scratched the surface of what’s to be learned about sleep and its age-old role in keeping us healthy. There’s much more intel to come. And there are emerging fields of research that will also contribute to our understanding. One of those involves climate and sleep disturbance.

“Our future is being dictated by global warming, which will hurt everyone but especially the poor and elderly,” Mednick says. “A new and important area of research shows that sleep will be one of the main biological functions that will be impaired with warming global temperatures.” She’s collaborating with Richard Matthew, associate dean of research and international programs in UCI’s School of Social Ecology and professor of urban planning and public policy, and Amir Rahmani, associate professor of nursing and computer science, to bring this issue to light. “We need to understand and investigate the impact of global warming on sleep and health so that we can come up with solutions,” Mednick says.

Until then, sleep tight — or try to. Rest assured that sleep is an important determinant of human health — and that, at least, is not going to change anytime soon.