Pride month in June commemorates the 1969 Stonewall uprising, when over the course of six days, LGBTQ people clashed with police over the raid of a New York gay bar, demanding the right to peacefully assemble. Since that time, many legal victories have been won, from the repeal of sodomy laws to the right to wed, adopt and even hold a job.

But Pride has always been about more than rights.

It has also been about self-expression — and that’s what UC Santa Cruz psychology professor Phil Hammack studies. His work seeks to understand the latest trends in LGBTQ identity, particularly among today’s teens, who are identifying as LGBTQ+ in greater numbers than any generation prior, and with greater diversity in labels around gender and sexuality. They are leading what he calls the next sexual revolution — a revolution of radical authenticity.

The times they are a’changing

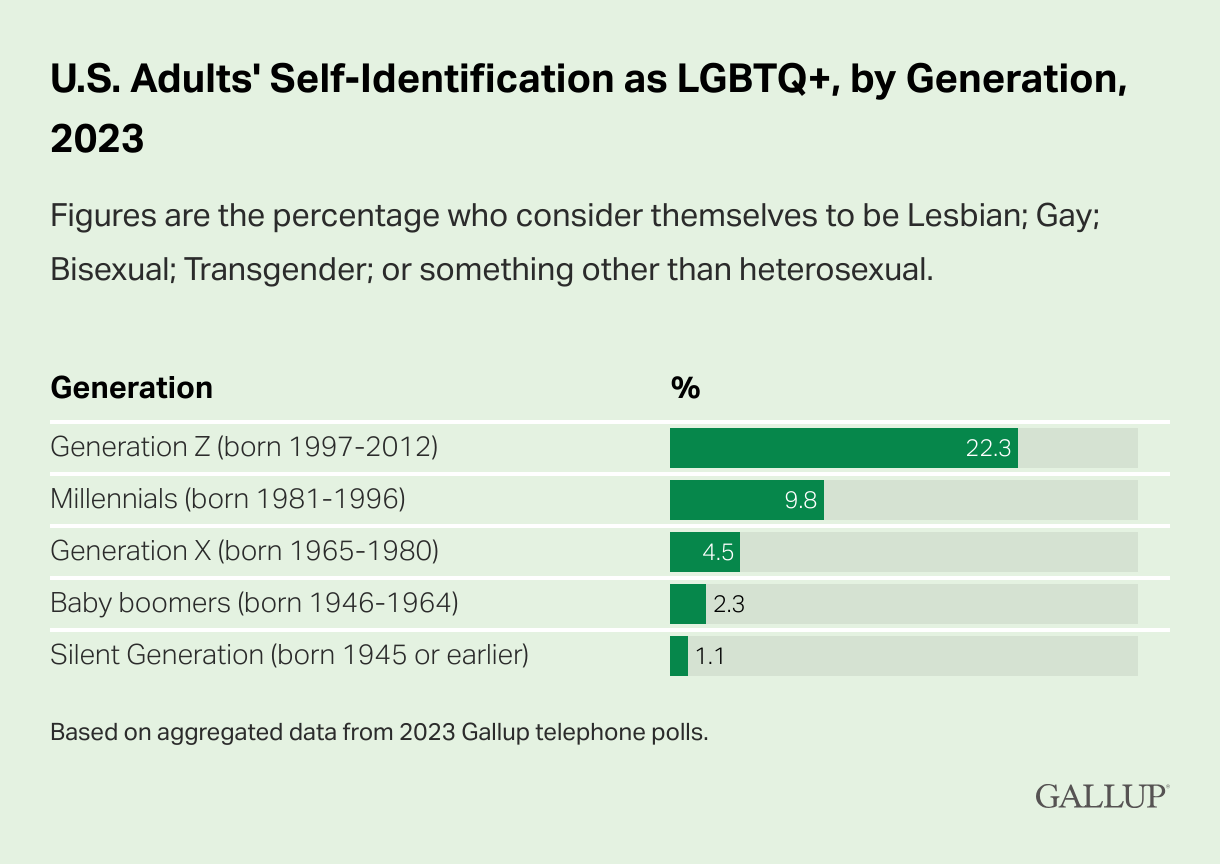

The world of sexual and gender identity is rapidly changing. In a Gallup poll released in March 2024, 7.6 percent of respondents identified as LGBTQ+, up from 3.5 percent in Gallup’s inaugural 2012 poll. This increase in self-identification has been met with alarm in some quarters, as some states and school districts attempt to ban books or restrict teaching on gender and sexuality.

That backlash is doomed to fail: The rise of the internet means people today have never-before-realized opportunities to ask questions about identity, learn and connect. So, it’s not too surprising that while each generation shows an increase in LGBTQ+ identification, the greatest surge comes from Generation Z (born between 1997 and 2012), who have had access to the internet almost their entire lives.

“I’m a member of Generation X, and a key difference between Gen X and subsequent generations is that Gen X had the internet in college, while millennials tended to have the internet in high school, and Gen Z can’t remember life without it,” Hammack says.

Hammack’s passion for his work comes from his own experiences of same-sex desire in high school, when depictions of gay life “centered around death, disease, and extraordinary stigma” in mainstream media, fueled by the AIDS crisis.

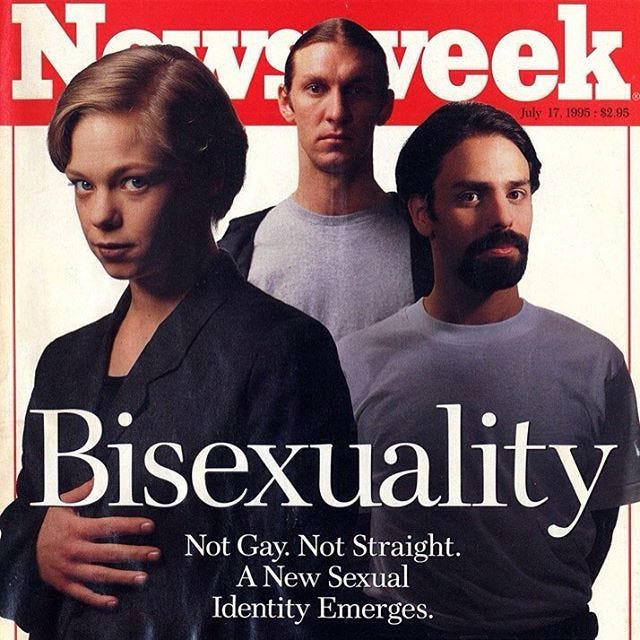

Before coming out as gay, Hammack initially came out as a bisexual, which was met with its own stigma in the 90s (it even got its own Newsweek cover in 1995). Over the past three decades, the journey of coming out has changed dramatically.

Phil Hammack

“Social technologies, whether it’s the early internet and chat rooms that millennials tended to experience in adolescence, or social media, like TikTok, that we think of now, have been the key driver in social and cultural change around our understandings of sexuality and gender,” Hammack says.

These changes, which Hammack has described as the “radical authenticity revolution,” don’t necessarily take the same shape as the sexual revolutions that date all the way back to the 19th Century and the feminist movement’s first wave, which advocated for numerous rights, including the right to vote. The gay rights movement of the 20th century likewise focused on inclusion in existing institutions. What’s both radical and authentic in this new revolution, according to Hammack, is the willingness to overturn categories that inclusion entrenched — man, woman, gay, straight — and the ability to look outside of traditional authority figures or information sources for language and validation, thanks to the internet. In a new paper authored with UC Santa Cruz psychology professor and social media expert Adriana Manago, Hammack articulates these new waves of internet-driven change, including the rise of subcultures of highly misogynistic straight men, whose use of online forums to affirm a cisgender, heterosexual male-dominated world order draws from the same access and technology as LGBTQ youth, just to different ends.

“Our big argument is that to understand what's happening in this century, which is very different from what happened the prior century, we really have to look at social technologies and understand the significance of their roles,” Hammack explains. “I see marriage equality, for example, as essentially the grand finale of the prior sexual revolution when it comes to minoritized sexual identities. It expresses this strong desire for primarily gay and lesbian people, same-sex couples, to share the social benefits of existing institutions.

“But a different sexual revolution is going on today, which is not about inclusion in cultural institutions like marriage. It’s about radically reformulating cultural institutions and breaking the myth of binary thinking around gender and sexuality.

“That was not something that I think my generation was necessarily focused on. It’s really been Gen Z that has pushed us to think much more expansively about gender and sexuality and argue for total change of institutions, whether it’s how we think about organized sports or bathrooms or pronouns, things conservative circles have been rebelling against pretty strongly.”

One identity not typically mentioned in hot-tempered political discussions of gender and sexual identify is that of asexuality, Hammack says.

“When I was first getting trained in professional psychology, we were trained it was a diagnosable sexual condition,” Hammack notes. “This is an example of where internet activism can literally change the way people think.”

An (a)sexual revolution

If you are aware of asexuality, or any identity that encompasses a persistent lack of sexual attraction, you likely have the work of activists like David Jay to thank. Jay founded asexuality.org, or AVEN (the Asexual Visibility and Education Network) in 2001 after years of struggle with his own identity and the lack of information on what he felt to be his authentic self.

July 17, 1995 Newsweek cover.

Like most other self-identifying asexuals, Jay wanted human intimacy, but didn’t experience a desire for sex as a means of necessarily experiencing that. Pre-Google search engines continually pointed him to a paper about plant reproduction when he input “asexual” into his browser. When he visited Stanford, where Google was in its earliest incarnation, he tried again on this new search engine, and found someone else who identified as asexual.

“Finding another person, or just any mention of asexuality at all, really collapsed my fears about whether I was allowed to be this way. There weren’t people telling me to be ashamed, but there were a lot of people telling me I’d be alone forever. And so, that was a really sort of pivotal, emotional moment,” Jay says. “It inspired me to make my own website to try to help other people because I found this one article, but the article was just one story. There wasn’t a place for people to talk to one another, and that’s what I wanted.”

As AVEN was beginning to grow, sex researchers were also beginning to explore the idea that this identity could in fact be a healthy one, and not a pathology. But at the time, the major handbook for human psychiatry practitioners, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edition, categorically defined a lack of sexual desire as a problem (hypoactive sexual desire disorder) that ought to be treated — an echo of past editions that had similarly pathologized same-sex desires and relationships.

“I was vaguely aware when I was younger that I did not trust mental health professionals to understand queerness,” Jay says. “I was struggling a lot but therapy didn’t feel like an option because I knew that therapists had taken way too long to accept homosexuality. And I had enough of a pop culture understanding of Freud to think, ‘they probably are not going to trust a lack of sexuality and probably not because it's actually a problem.’”

In 2008, Jay and other activists from AVEN formed a task force to provide qualitative and quantitative data from their network and experiences to the medical team working on revising the DSM for its 5th edition. The top policy priority of AVEN’s community was better psychiatric care and understanding — to advocate for a model of care that understood what positive development for an asexual-identifying youth looks like.

AVEN was not alone in this journey, garnering support from scientists like Anthony Bogaert, who put the identity on the research map. His 2004 paper launched the field of asexuality studies, finding about 1 percent (or around 580,000 people) of the British population could be defined as asexual. The 5th edition of the DSM, released in 2013, now accepts low or nonexistent sexual attraction as normal when it occurs for a person identifying as asexual, while making room for those experiencing distress over a lack of sexual attraction to seek help.

A safer internet

AVEN has continued to grow, with 143,000 members as of 2022, and is now a major resource for those studying asexuality. Jay remains involved with AVEN as a board member, but his work has also taken him to the Integrity Institute and Fairplay, both organizations that seek to put up safeguards for young people searching — as he once did — for real information on the internet.

The internet is a powerful tool for exploring identity — an oft-overlooked aspect of Gen Z’s relationship with the online world, Hammack says, is that a human sitting in front of a computer inputs the queries.

“They are an active agent who's driving the process that ultimately leads to an algorithm that they’re exposed to,” Hammack says. That’s the piece that gets de-emphasized, he notes, which goes against the notion, in some conservative circles, that the internet is the active agent making kids identify as one way or another.

“In the research I’ve done with queer teens when they talk about social media, they talk about going there and looking for things,” Hammack says, “not, ‘I had no idea what was going on and all of a sudden this thing came at me online.’ What gets lost in debates is that labels are linked to real experiences people have of desire and the self, and the pain that people experience from not being able to put a name to that. Underneath all of the aspects of social change that may irritate some people is someone who is thinking, ‘oh my God, I can’t believe I finally have a name for how I feel.’”

David Jay

But rising visibility also means rising vulnerability, or what Hammack calls the paradox of the present. “When you dig deep into the psychological struggle queer kids experience, it’s not because they feel awful about being pansexual, for example — totally the opposite. Queer communities and friends are a source of strength. But there is a really despondent reaction to schools, or a lack of mainstream education or acceptance, even in what we would think of as progressive communities. People diverse in genders and sexuality don’t feel like they have that kind of institutional support.”

Teen distress comes from discrimination, cyberbullying, emotionally manipulative algorithms and misinformation. Jay, now a parent of two children, is working to mitigate this for the next generation through organizations driven to provide guardrails for teen mental health.

“I want to see places where queer teens can receive authoritative information and ideally wind up in community with other young people and with elders who respect and have been through that journey,” Jay says. “Along the way, I’m really concerned about ways that their privacy can be violated, potentially by families who are not supportive, or ways that online channels can become avenues for online harassment.

“From working with families who’ve lost kids, I can see how bad algorithmic recommendations and online harassment can get. TikTok and Instagram algorithms will happily say: ‘You seem a little depressed. Do you want nothing but content about depression for four hours a day?’ That makes me really, really worried.”

Jay points to legislation around online safety and improved platforms, like Blue Fever, an app that supports teen socializing and mental health with qualified adult mentors, as a way of reducing this risk. For as much as artificial intelligence is preparing to catapult the internet into its next iteration, “an algorithm can’t replace a mentor,” Jay says. While the internet can expand identity and validate self-concepts, it needs to offer places of belonging to do that.

This revolution, as it turns out, still needs people behind its screens.

Banner image: iStock/Rawpixel