Mike Peña, UC Santa Cruz

New research shows that whales move nutrients thousands of miles—in their pee and poop—from as far as Alaska to Hawaii, supporting the health of tropical ecosystems and fish. UC Santa Cruz professors Dan Costa and Ari Friedlaender contributed their marine-mammal expertise to the study, which was published on March 10 in the journal Nature Communications.

Led by University of Vermont biologist Joe Roman, the research underscores that whales are not just huge—they're a huge deal for healthy oceans. The study calculates that in oceans across the globe, great whales—including right whales, gray whales, and humpbacks—transport about 4,000 tons of nitrogen each year to low-nutrient coastal areas in the tropics and subtropics. They also bring more than 45,000 tons of biomass.

In addition, before the era of human whaling decimated populations, these long-distance inputs may have been three or more times larger. Hence, the co-authors also discuss how species recovery might help restore nutrient transfer by whales in global oceans and increase the resilience of the enriched ecosystems.

“Recently, we demonstrated how much commercial whaling impacted nutrient recycling by whales in their feeding grounds, and this work augments our understanding of how tropical systems are also impacted,” said Friedlaender, a professor of ocean sciences. “Given that these warm-water ecosystems are even more nutrient-limited than those in polar regions, the impacts may be even greater in the areas where baleen whales commonly breed and give birth.”

In 2010, scientists revealed that whales, feeding at depth and defecating at the surface, provide a critical resource for plankton growth and ocean productivity. Now, this study shows whales also carry huge quantities of nutrients horizontally, across whole ocean basins: from rich, cold waters where they feed to warm shores near the equator where they mate and give birth. Much of this is in the form of urine—though sloughed skin, carcasses, calf feces, lactation, and placentas also contribute.

A living ‘conveyor belt’

But because much of these metabolic processes are difficult to directly observe among these great whales throughout their migration, the research team turned to the marine-mammal experts at UC Santa Cruz. Leveraging the university's long-running research on northern elephant seals at Año Nuevo Natural Reserve, Costa estimated the amount of nitrogen that would be released while the whales were fasting by scaling up the metabolic processes of the seals to that of a whale.

"While elephant seals and great whales would seem to have little in common at first glance, they are, in fact, both extreme capital breeders," said Costa, a distinguished professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. "They acquire the resources necessary to produce young thousands of miles from where they give birth."

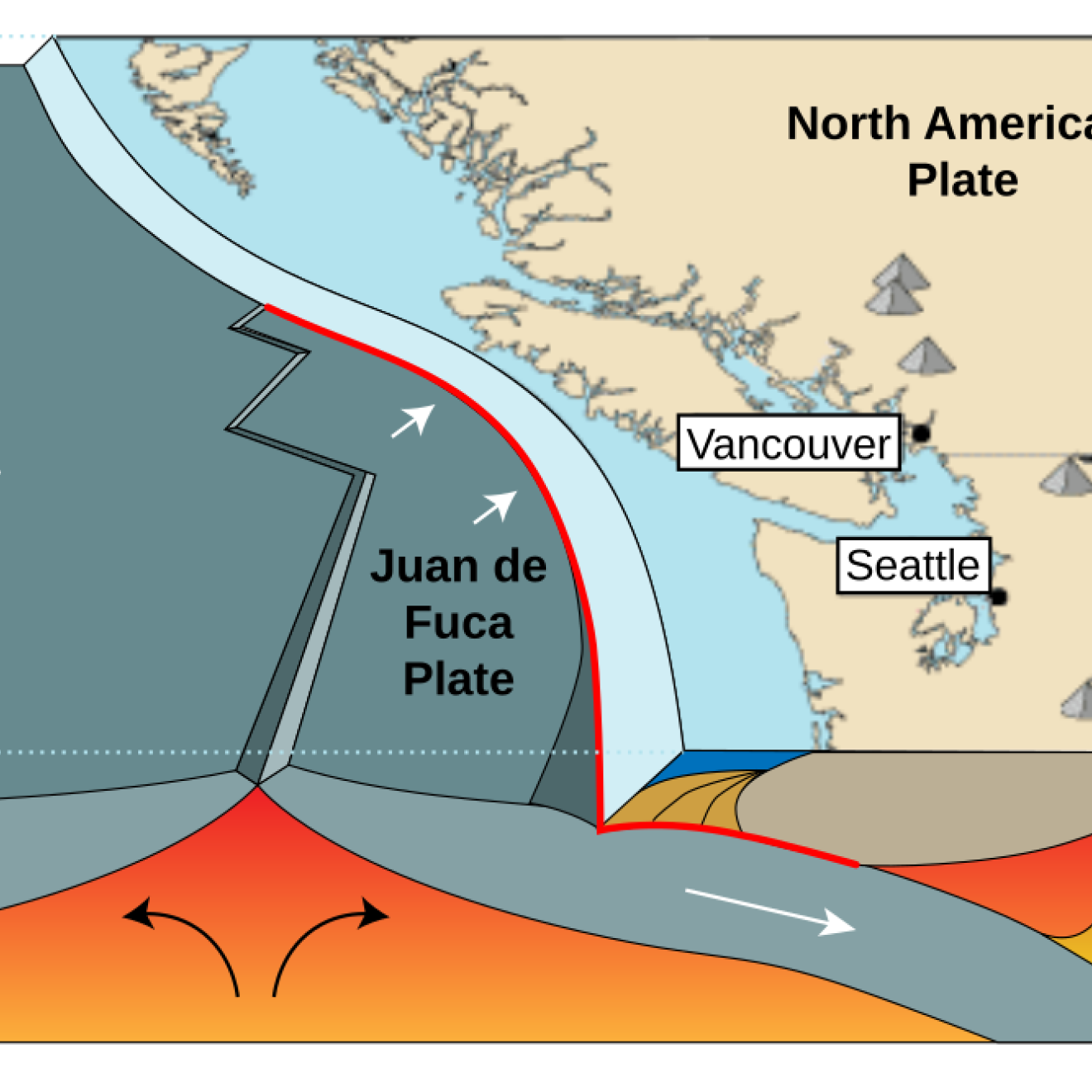

This redistribution of nutrients is known as the “great whale conveyor belt,” which is illustrated by the thousands of humpbacks that travel from a vast area where they feed in the Gulf of Alaska to a more restricted area in Hawaii, where they breed. There, in the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary, the input of nutrients from whales roughly double what is transported by local physical forces, the team of scientists estimate.

In the summer, adult whales feed at high latitudes—like Alaska, Iceland, and Antarctica)—putting on tons of fat, chowing down on krill and herring. According to recent research, North Pacific humpback whales gain about 30 pounds per day in the spring, summer, and fall. They need this energy for an amazing journey: As Costa points out, baleen whales migrate thousands of miles to their winter breeding grounds in the tropics—without eating.

For example, gray whales travel nearly 7,000 miles between feeding grounds off Russia and breeding areas along Baja California. Humpback whales in the Southern Hemisphere migrate more than 5,000 miles from foraging areas near Antarctica to mating sites off Costa Rica, where they burn off about 200 pounds each day, while urinating vast amounts of nitrogen-rich urea.

For perspective, fin whales produce more than 250 gallons of urine per day when they are feeding, a study in Iceland suggests. Humans pee less than half a gallon daily.

“Because of their size, whales are able to do things that no other animal does. They're living life on a different scale,” said Andrew Pershing, one of ten co-authors on the new study and an oceanographer at the nonprofit organization, Climate Central. “Nutrients are coming in from outside—and not from a river, but by these migrating animals. It’s super-cool, and changes how we think about ecosystems in the ocean. We don't think of animals other than humans having an impact on a planetary scale, but the whales really do.”

Out of the blues

Before industrial whaling began in the 19th century, the nutrient inputs would have “been much bigger and this effect would've been much bigger,” Pershing said. Plus, the nutrient inputs of blue whales—the largest animals to ever live on the Earth—are not known and were not included in the primary calculations of the new study. In the Southern Ocean, blue whale populations are still greatly reduced after intense hunting in the 20th century. “

Both blue whales and humpbacks were depleted from hunting, but some humpback and other whale populations are rebounding after several decades of concerted conservation efforts.

“Lots of people think of plants as the lungs of the planet, taking in carbon dioxide, and expelling oxygen,” said Roman. “For their part, animals play an important role in moving nutrients. Seabirds transport nitrogen and phosphorus from the ocean to the land in their poop, increasing the density of plants on islands. Animals form the circulatory system of the planet—and whales are the extreme example.”