Sandra Baltazar Martínez, UC Riverside

Looking at American life through literature is a great way to remind people that Americans have more shared experiences rather than differences, said Susan Straight, author and distinguished professor of creative writing at UC Riverside.

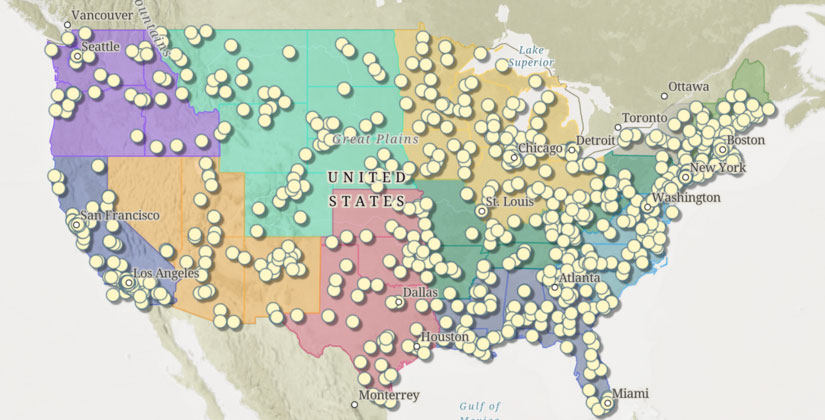

With the 2024 presidential elections around the corner, it is important to remember the shared humanity, love for family, and respect for neighbors, said Straight, who spent five years reading 1,001 novels that document American life. Last year she worked on a project alongside an Esri engineer to display those novels across an interactive U.S. map.

“This is my love letter to the United States, to our powers of narrative and laughter, to the way we need to treasure every region of this extraordinary country, with geography that shapes all our lives, to honor the rivers and mountains, subways and freeways, deserts and forests, bayous and canyons of the nation,” Straight said in an essay introducing the project.

The map is divided into 11 regions and the 1,001 number is a tribute to Scheherazade, the central female character and storyteller in “The Arabian Nights.”

Straight calls the project a “Library of America,” born in 2016 when news stories were constantly inching at dividing America along party lines.

Straight is the author of 10 books, her most recent is “Mecca,” a novel that weaves the past and present into stories that reflect the lives of millions of ordinary people in the Inland Empire. She says she always writes about “characters trying to find home, even if they migrate, how they carry home with them in language, food, and story, just as my own mother did when she arrived in Fontana, California, at 19, from the Alps of Switzerland.”

Q: Can reading serve as a healing agent in this current divisive political climate?

A: I began working on the first edition of this Library of America literary map in January 2017, on an Inauguration Day when the news media kept declaring the election had made clear that America was divided into Red and Blue states, I kept seeing the huge maps everywhere, showing only those two colors, as if there were no places more complicated than politics.

That night, scenes from so many novels came into my head, places like Ernest J. Gaines’ Louisiana, Louise Erdrich’s North Dakota, Kent Haruf’s Colorado, and Grace Paley’s New York. I began writing down titles and wanting to make a beautiful map of America where home was the defining illustration for each novel.

One of my former students, Vanessa Hua, calls the places I write about, in Southern California, “hidden kingdoms,” and I love that – she writes about the Bay Area, my former student Alex Espinoza writes about East LA and Colton.

Working with Esri was a joy – we found covers for the first editions of 737 books that year, and I delved deeply into GIS to find specific locations for each book, often reading old interviews with authors long passed away.

Literature takes us to places we might already know and love, but more often, it allows us to travel somewhere we might never visit, to hear people speaking as they do in Chicago or Boston or Washington D.C., or in small towns of Kansas or Virginia or New Mexico, those specific regional languages that make America fascinating and beloved.

Reading can heal us, can make us understand each other as neighbors in any city or town, whether our parents came from another country two generations ago, or arrived last year, whether we work as landscapers or tech giants, whether we share a faith or believe differently. Story lets us linger with strangers, and friends.

Q: Through the 1,001 novels featured in this project, what shared experiences stood out to you? What common threads unite Americans?

A: The larger second edition of the map, 1001 Novels, was finished in May 2023, published with Esri and the Los Angeles Times, and shared hundreds of thousands of times around the world.

So many common threads became clear as I continued to work on the project. Many novels were about young people and their animals, classics like “Old Yeller,” set in Texas, “Sounder,” set in Louisiana, “My Friend Flicka,” set in Wyoming, and “The Yearling,” set in Florida. Many great novels were about teens and young adults navigating their identities in dangerous or violent situations, sometimes because of their backgrounds – these include “Finding My Voice,” by Marie Myung-Ok Lee, set in 1970s Minnesota, “Under the Feet of Jesus” by Helena Maria Viramontes, set in Central California, and “Holes,” by Louis Sachar, set in Texas, as well as classics such as “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn” by Betty Smith.

Maybe my favorite aspect of working for years on this map is how many “hidden kingdoms” I discovered where the landscape leads to loyalty, family and survival, from Indigenous peoples in 1870 Montana Territory in James Welch’s “Fools Crow” to Irish American neighborhoods in Dennis Lehane’s “Mystic River” and Michael Connelly’s “Los Angeles,” where as his detective Harry Bosch says a truth I believe: Everybody counts, or nobody counts.