“We talk about the weather every day, but there’s no direct market for weather. You can’t go out and buy a nice day,” said Patrick Baylis, a fifth-year Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics at UC Berkeley.

Economic models already predict how warming climate will hurt our wallets – by one recent estimate, incomes will drop by roughly 23 percent over the next four decades from a climate-induced economic slowdown.

But current models can’t capture everything, particularly the human side of the equation. Will our response to increasing temperatures help or make things worse?

To answer this question, Baylis looked to an enormous, freely accessible database of human emotions: Twitter.

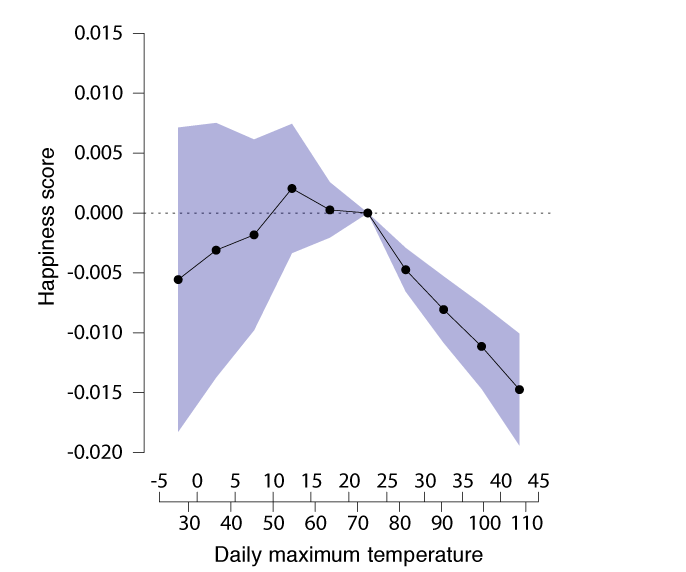

In a recently released working paper, "Temperature and temperament: evidence from a billion tweets," Baylis analyzed the sentiment of over 1 billion geotagged tweets from U.S. Twitter users. When he correlated the tweets with local weather data, a clear pattern emerged: heat makes people miserable.

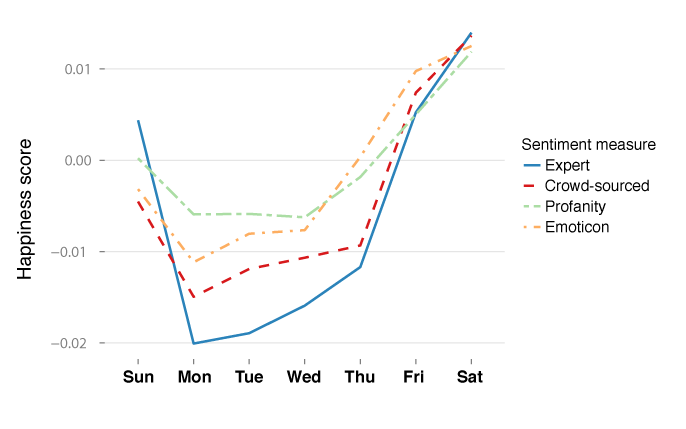

How miserable? Baylis likes to explain it in a way that people can easily relate to: the drop in happiness the average American feels from Sunday to Monday (which he also measured from the same Twitter data) is comparable to the drop in happiness between a day in the range of 60-70 degrees Fahrenheit to a day in the 80-90 degree range.

The upshot? Imagine the world struggling to deal with the effects of climate change, while everyone has a bad case of the Mondays.

Average happiness of tweets by day of week, scored with four different sentiment analysis techniques.

Hot under the collar

There’s good reason to think that hot weather might make people less happy, angrier and even more violent.

“Anecdotally, our language suggests that we already think this is the case, which is why we use phrases like ‘hot headed’ and ‘hot under the collar,’” said Baylis. "There are also literary examples: early in Albert Camus’ ‘The Stranger,’ the main character partly blames a murder on the heat. This kind of research helps us quantify the magnitude of these effects.”

Previous research by UC Berkeley’s Solomon Hsiang and colleagues found a correlation between higher temperatures and events of human conflict through history, via meta-analysis of 60 studies spanning fields from economics to archaeology. Beyond simple discomfort, other research has found that heat can have a physiological effect on the brain, resulting in more emotional and aggressive behavior.

A 2015 study from Hsiang’s group found that higher temperatures are likely to benefit some areas of the world, increasing productivity in colder, northern countries such as Russia and Canada. In other places, productivity will strongly decrease due to high temperatures.

The challenge facing economists is to create models that capture the complexity of all of these factors, allowing governments to plan and adapt appropriately.

How to measure happiness in a tweet

Tweets don’t come with happiness scores: Baylis had to take over 1 billion tweets and use sentiment analysis techniques to score their “hedonic state,” i.e., where they fall on a scale from happy to unhappy. Sentiment analysis of text is notoriously prone to error, particularly when ambiguity and sarcasm come into play, which they do frequently on Twitter, but by looking at a sample size of over 1 billion, Baylis’ minimized the effect of occasional misreads.

Additionally, Baylis used four separate methods of sentiment analysis to verify his results, relying upon expert and crowd-sourced dictionaries, and the presence of profanity or emoticons within a tweet. He verified these approaches by examining tweets guaranteed to contain raw emotions: posts near NFL stadiums following football games. (If you were angry or thrilled after an NFL game in 2015 and tweeted about it, you helped science.) Each of the four football-calibrated methods produced the same pattern: hot tweets are significantly less happy.

Effect of temperature on happiness or "hedonic state" from over 1 billion tweets from across the USA. Above 72.5 degrees Fahrenheit, average happiness score declines.

There’s a lot of nuance to the data, which Baylis is continuing to explore. Is it the heat or the humidity that bothers people? It appears to be both together. Tweets from hot and humid days are significantly less happy than those from just hot days.

Extreme cold is not the worry when it comes to climate change, but Baylis is still looking into the effects on the cold end of the range, because the variation in response is much greater and the pattern is less clear.

“If it’s cold, you can always put on a sweater,” explained Baylis. “But on hot days, there’s only so much you can do.”

How will humans adapt?

Proving that hot weather decreases happiness is just the first step. Baylis is interested in getting a better understanding of the human capacity to adapt to a changing climate. Preliminary results indicate that people from hotter regions are still affected by high temperatures, but perhaps to a lesser degree.

Baylis’ goal is to help improve the economic models and put his findings in monetary terms.

How much will loss of happiness cost us relative to other damages from climate change? That remains to be seen.

In the meantime: if it’s hot outside, maybe stay off Twitter.