Sean Nealon, UC Riverside

A team of scientists from the University of California, Riverside and three Mexican universities have received about $5 million in funding to support research to continue development of a novel transparent skull implant that literally provides a “window to the brain.”

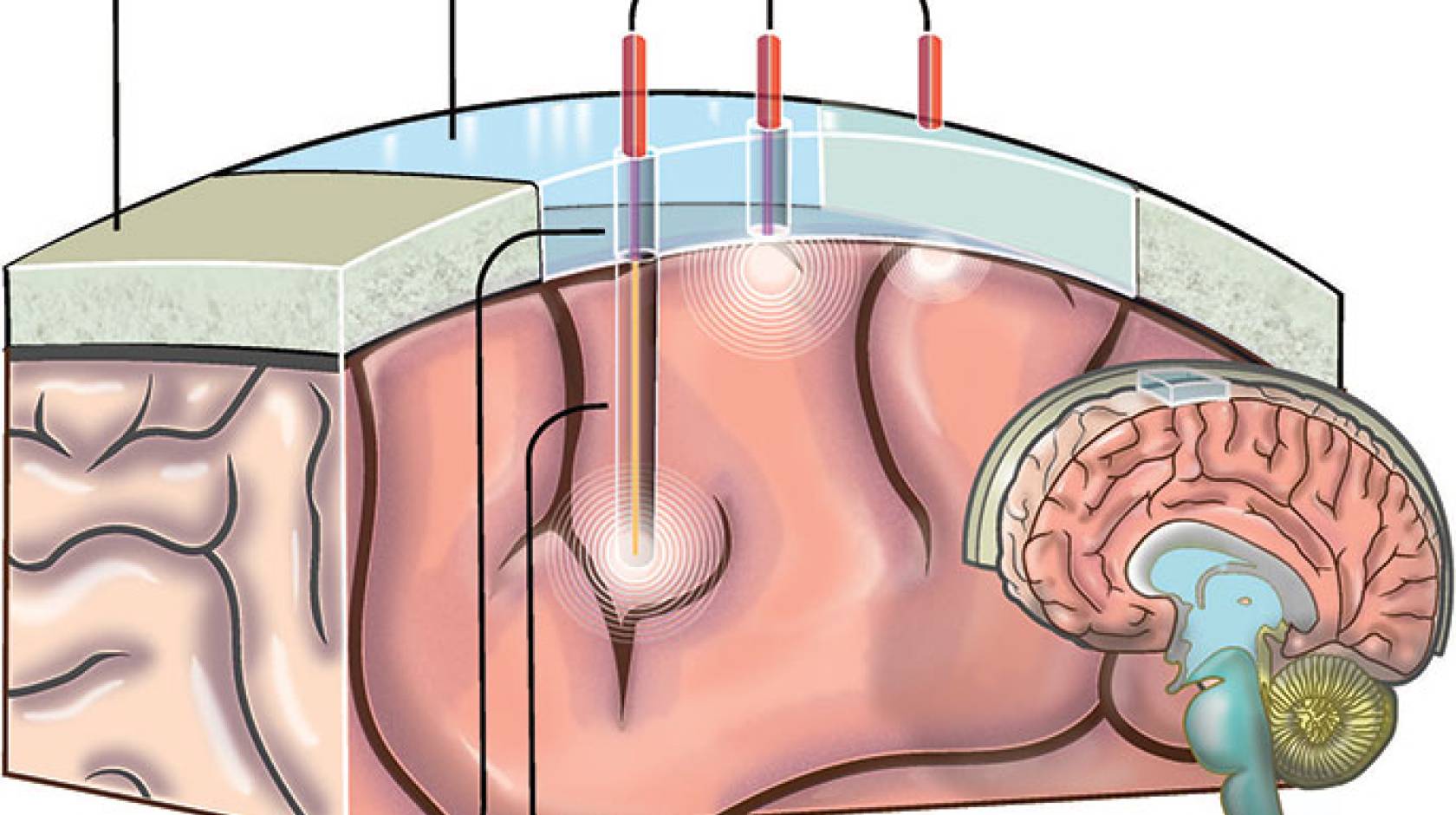

Two years ago, the UC Riverside scientists announced they had created the skull implant, which is made out of the same ceramic material used for hip implants and dental crowns.

However, the material, yttria-stabilized zirconia, is processed in a unique way that makes it transparent. When combined with the excellent biocompatibility and robustness of the zirconia, this may eventually provide opportunity for laser-based treatments of life-threatening disorders such as brain cancer or traumatic brain injury without having to perform repeated craniotomies, which are highly-invasive surgical procedures that involve removing a portion of the skull to access the brain.

The new funding will allow the researchers to study new material developments that could provide further enhancement of important implant properties, such as toughness; shaping the implant so it conforms to the curvature of the skull; how lasers react when passing through the ceramic implant; and how the implants respond in animal studies.

Funding from U.S., Mexican sources

The majority of the funding, $3.6 million, comes from the National Science Foundation’s Partnerships in International Research and Education (PIRE) program, which pairs U.S. universities with others around the world. An additional $1 million will come from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT), Mexico’s entity in charge of promoting scientific and technological activities. The remainder of the money will come from in-kind contributions from the Mexican universities.

The project is led by Guillermo Aguilar, a professor of mechanical engineering at UC Riverside’s Bourns College of Engineering who is originally from Mexico. Five other UC Riverside professors are involved: Javier Garay, Lorenzo Mangolini, Masaru Rao, Huinan Liu and Devin Binder. All are part of the Bourns College of Engineering, with the exception of Binder, who is part of the School of Medicine. In addition, David Halaney, a junior specialist, will help oversee activities related to the grant.

Three faculty members from Mexican universities are also involved: Santiago Camacho-López, Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada (CICESE); Juan Hernández-Cordero, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM); and Rubén Ramos-García, Instituto Nacional de Astrofísica, Óptica y Electrónica (INAOE) in Puebla.

Alignment with other educational initiatives

The five-year project, known as Synthesis of Optical Materials for Bioapplications: Research, Education, Recruitment and Outreach (SOMBRERO) program, aligns with current education policy initiatives in the U.S. and Mexico.

These include President Obama’s Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) initiative, as well as his “100,000 strong in the Americas” initiative to increase study in Latin America and the Caribbean; Presidents Obama and Peña-Nieto’s student mobility initiative, the Binational Forum on Higher Education, Innovation, and Research; and the UC Office of the President’s UCMEXUS program and UC-México Initiative, all of which seek to create sustained, strategic and equal partnerships among U.S. and Mexican institutions to address common issues and educate the next generation of scientific leaders.

The SOMBRERO program will allow students from UC Riverside and the Mexican universities to take part in six- to 12-month internships in the other country.

Laser-based treatments have shown significant promise for many brain disorders. However, realization of this promise has been constrained by the need for performing a craniectomy to access the brain since most medical lasers are unable to penetrate the skull. The transparent implants developed by the UC Riverside team seek to address this issue by eventually providing a permanently implanted view port through the skull.

Although the team’s yttria-stabilized zirconia windows were not the first transparent skull implants, they are the first that conceivably could be used in humans, which is a crucial distinction. This is due to the inherent toughness of yttria-stabilized zirconia, which makes it far more resistant to shock and impact than the glass-based implants previously demonstrated by others. This not only enhances safety, but it may also reduce patient self-consciousness, since the reduced vulnerability of the implant could minimize the need for conspicuous protective headgear.