Julia Busiek, UC Newsroom

Wildfire season in California is getting longer, more intense and more destructive. That means millions more Californians breathe polluted air more often as smoke drifts into skies across the state.

UC experts have answers to critical questions about this new reality: What’s in wildfire smoke that makes it so harmful? What happens to our bodies when we breathe it in? And what can governments and everyday Californians do to reduce the health risks of fire season?

How air pollution affects your body

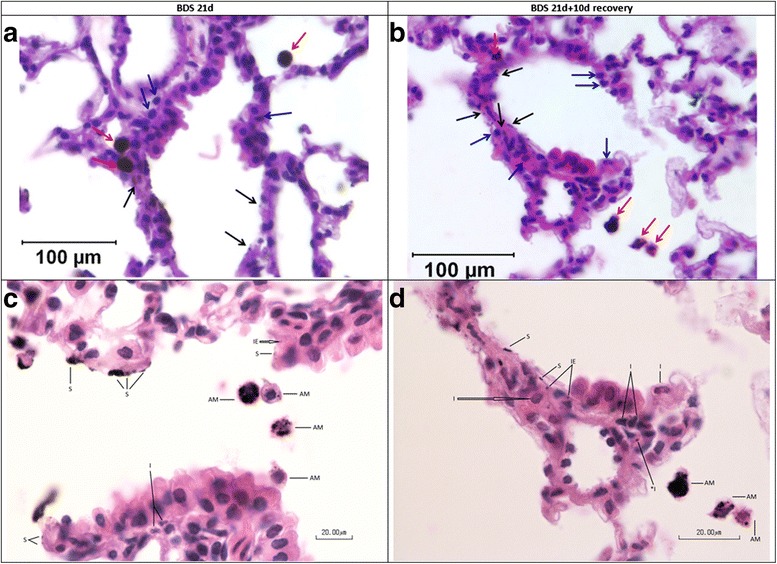

The most common measure of air pollution — the number you’ll see reported on apps like PurpleAir — is the concentration of PM2.5, or microscopic particles smaller than 2.5 micrometers. Depending on the source of pollution, these particles can contain dirt, soot, heavy metals, chemicals, pollen, mold and more. Whatever they’re made of, these particles are all small enough to skirt your upper respiratory defenses and wind up deep in your alveolae, the delicate membranes in your lungs that exchange gases between your circulatory system and the outside world.

Satellites images from September 2020 capture smoke from fires up and down the state.

“The reason we monitor, measure, study and regulate PM2.5 is that when it gets into the alveolae, it can get into your bloodstream, and then it goes everywhere throughout your body, including vital organs” says Tarik Benmarhnia, an environmental epidemiologist who studies the health effects of wildfire smoke at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography. “And that can lead to some negative consequences.”

As you might expect, people exposed to air pollution have higher rates of respiratory diseases like asthma. But UC research is finding that the risks of breathing in toxic air go way beyond your lungs. Researchers at UC Davis are finding links between air pollution and blood clots, stroke and arrhythmia. One study from UC Irvine found that breathing in traffic exhaust caused memory loss and triggered neurological pathways that lead to Alzheimer’s disease, and another linked long-term exposure to polluted air with higher rates of postpartum depression. And UC San Francisco researchers identified a link between PM2.5 and COVID-19 infections.

UC San Diego environmental epidemiologist Tarik Benmarhnia.

Why does PM2.5 cause so much trouble for our bodies?

Benmarhnia cites three main sources: inflammation, oxidative stress and weakened immunity.

When it clocks pollution particles, your immune system first responds with inflammation, generating heat and bombarding the point of entry with specialized cells meant to attack anything your body recognizes as foreign. Inflammation is good when it fights off viruses and bacteria, but too much of it for too long can also wear down your organs and contribute to chronic conditions like heart disease and diabetes.

Meanwhile, our bodies’ constant work of breathing, digesting and moving generates waste molecules, which can damage your cells if they hang around and accumulate. To counter this damage, known as oxidation, your cells produce antioxidants, molecules that act like a cleanup crew. But some substances commonly found in air pollution can react with your cells in a way that generates more damaging waste and throws off the balance of antioxidant defense. Studies have found evidence of this process, known as oxidative stress, in the lungs, heart, brain, liver and kidneys of people and animals exposed to air pollution.

Finally, breathing in PM2.5 can depress your immune system. In part that’s because your body works so hard to respond to the flood of incoming particles that it’s likelier to let a harmful virus or bacteria slip through, Benmarhnia says. What’s more, some ingredients in PM2.5 actually attack specific parts of your immune system. Studies have found that iron from air pollution, for instance, can weaken macrophages, the white blood cells that gobble up invading microorganisms. The result? “Your immune system is lazier than it would normally be,” leaving you more vulnerable to infections of all kinds, Benmarhnia says.

Wildfire smoke: 10x more harmful than "regular" air pollution

Wildfire is far from the only source of air pollution in the Golden State. Traffic, freight, industry and agriculture also release PM2.5, meaning millions of Californians breathe perennially polluted air. “But wildfire smoke is very special,” Benmarhnia says. Wildfires typically burn much hotter than car engines or industrial machinery. “That’s going to increase what we call its oxidative potential, which basically means it’s much more active and can be very, very toxic.”

In a 2021 study in Southern California, Benmarhnia’s team found that an increase of 10 micrograms of PM2.5 from typical sources of pollution led to roughly a one percent increase in hospitalizations for respiratory conditions. An equivalent increase in PM2.5 from wildfire smoke, meanwhile, caused respiratory hospitalizations to jump by 10 percent. “So you could basically say particulate matter from wildfire smoke is up to 10 times more harmful than ambient air pollution,” Benmarhnia says.

As a warmer climate as collided with ever-more-overgrown wildlands across California, wildfire smoke has pretty quickly gone from an occasional, localized nuisance to a statewide threat. State data show Californians’ average smoke exposure was 3.6 times higher during 2017–2023, compared to 2010–2016. And a UCLA study published this summer found that wildfire smoke was to blame for 52,000 premature deaths in California between 2008-2018.

Potential population exposures to wildfire smoke, 2010-2023

This graph presents “person days,” or the estimated number of people living where smoke plumes were present, multiplied by the number of days when the plumes were present. Get maps and more data from the California Office of Environmental Health and Hazard Assessment.

Benmarhnia’s 2021 study gets at how science, policy and public health guidance have failed to keep up with this new reality. When you pull up an air quality app on your phone, it’s only going to give you the concentration of PM2.5 in the air you’re breathing. It’s not going to tell you what that particulate matter is made of. “Right now, in the U.S. and globally, in regulation and research, there is no differentiation between PM2.5 from wildfire, from traffic, from industry,” Benmarhnia says. “And that’s a problem. It all gets the same name, but it’s clearly not the same risk.”

How to protect yourself

“There is no safe level of exposure to air pollution,” Benmarhnia says. Study after study has shown that higher concentrations and longer duration affect people more severely, but even small amounts of pollution can affect your health. “So we should do everything we can to reduce our exposure as much as possible.”

Here are some steps you can take:

-

Keep an eye on your local air quality using apps like PurpleAir, but remember that these apps don’t tell you the composition of the pollution — just its concentration. If you smell smoke or you know you’re downwind of a wildfire, air quality readings are probably underestimating the hazards.

-

When air quality reading tip into “unhealthy” territory, stay inside.

-

If you can’t stay inside, wear a clean, NIOSH-certified N-95 face mask. Check out tips from California Air Resources Board for making sure your mask meets safety standards, and for getting the fit right.

-

Avoid exerting yourself outside, since that will make you breathe harder and draw more pollutants into your lungs. “It’s not a good idea to go for a run outside during a smoke event,” Benmarhnia says.

-

Once it’s inside your home, particulate matter can react with dust and generate even more pollution. So when it’s smoky, or before the smoke arrives, it’s a good idea to dust, mop and vacuum more often than you normally might.

-

Keep your windows closed and use an air filter. The mutual aid organization Common Humanity Collective, which originated at UC Berkeley in 2020, has instructions to make an affordable air filter using materials you might have laying around your house.

-

If you can’t seal your house and filter your air, or if you don’t have an AC and it gets too hot, consider taking refuge at a California Clean Air Center. Kind of like cooling centers during a heat wave, clean air centers are public spaces operated by local governments where anyone can go to get a respite from air pollution.

Alone, you can’t do a lot to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions, change forest management practices or prevent wildfire ignitions. But you can keep yourself and your family safer when fires do happen — as they probably will, more and more often.

“A lot of Californians are surprised each time we have these smoke events, even though in many places they now happen year after year,” Benmarhnia says. “People still consider wildfire to be exceptional, but it’s not anymore.”