Julia Busiek, UC Newsroom

Avian flu does not currently pose a widespread risk to human health. However, California farmworkers are on the front lines of rising human case numbers as the virus burns through California’s poultry and dairy industries. And the effects of the flu are hitting the state’s agricultural economy hard and jacking up the price of eggs for all.

It's also causing havoc for wild animals, including right here at UC: The peregrine falcons that nest in the bell tower at UC Berkeley haven’t been seen for two months, and are presumed to have died of the virus.

“Avian influenza is not new — it has been around for decades,” said Mark Stetter, dean of the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. “But what is new is this virus is changing, and it’s changing in multiple ways that have raised concerns lately.”

Stetter spoke at a recent UC Health Grand Rounds, where he joined a panel of experts from UC Davis to share the latest information about the virus — also known as H5N1 — and how it’s affecting people and animals across the Golden State.

Why did scientists start to take notice of this outbreak?

“The current H5N1 outbreak has been going on for longer than you may realize,” said Dr. Ashley Hill, director of the California Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory at UC Davis. This strain of the virus has been infecting waterfowl around the world since 2020, and has since spilled over into other wild birds, domestic poultry and several species of mammals, including house cats.

In 2023, UC Davis researchers documented an outbreak among seabirds and marine mammals along the coast of South America that eventually killed over 17,000 animals. It was “the first indication that we were then entering an entirely new scenario for H5N1,” said Dr. Christine Johnson, professor of epidemiology and ecosystem health at UC Davis. Not only was the virus on that continent for the first time, but it seemed to be spreading not just from birds to mammals, but from mammal to mammal.

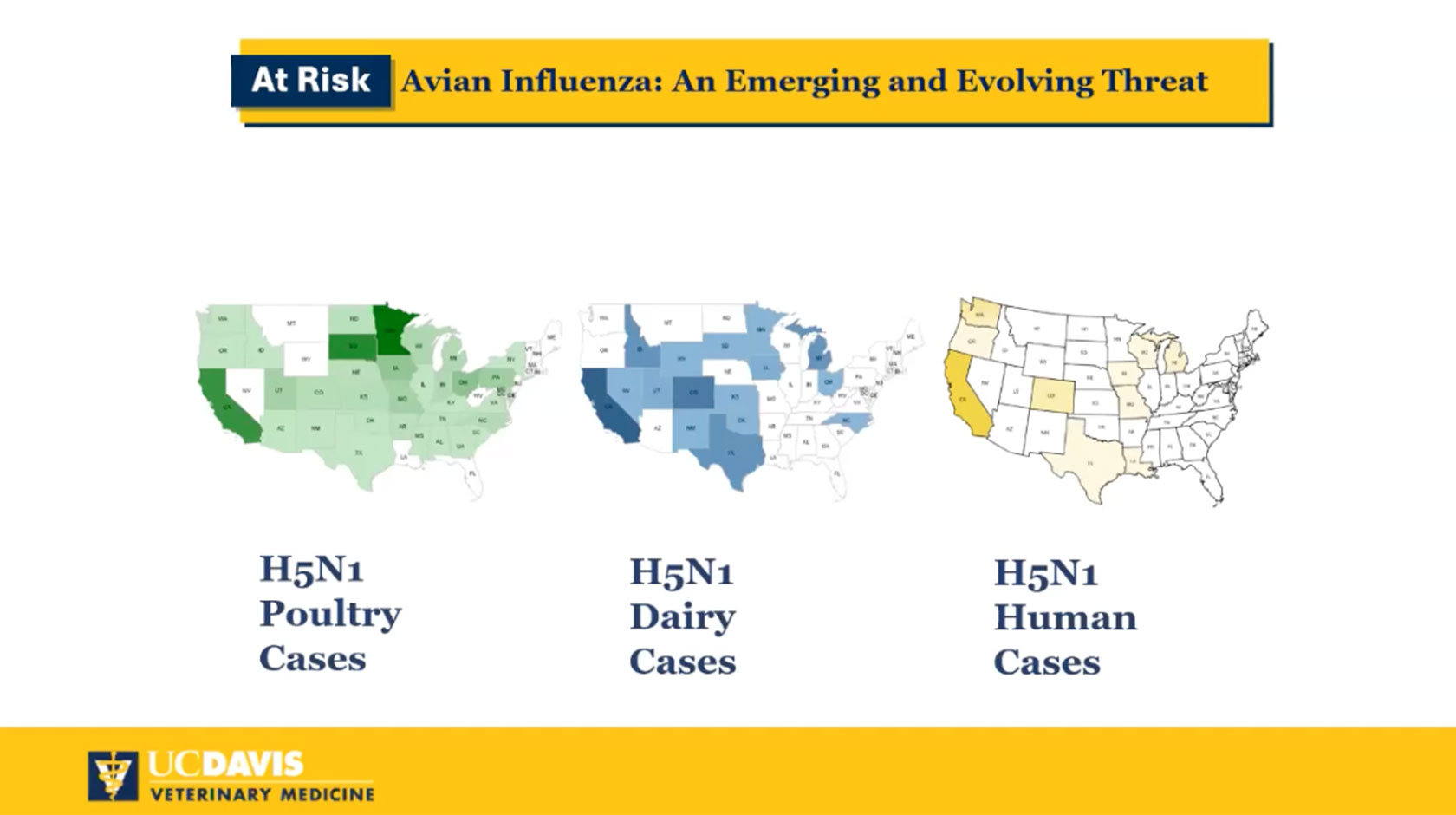

Then, in March 2024, the virus spread from a wild bird to a dairy cow in Texas, and it’s now circulating widely between cows and dairies across the United States.

Altogether, “We are now in a new, much more complicated scenario for H5N1,” Johnson said. The wider H5N1 spreads among animals and the more times it jumps from an animal to a human, the more chances it has to mutate into a form that could spread between people. “Human-to-human transmission would, of course, facilitate the type of rapid spread that we saw in the pandemic most recently,” Dr. Johnson said.

Can it spread to people?

Yes. Over 900 cases of H5N1 in humans have been documented since 1997. Aside from a single case in 2022, it’s only been in the past year that H5N1 has been detected in people in the United States. At least 70 people in 13 states have tested positive, the majority of them in California. Nearly all of people who've contracted the disease were exposed to sick animals on poultry or dairy farms, making California farmworkers a community of special concern for public health officials responding to the virus's spread.

Who is most at risk?

People who come into contact with sick or dead animals or products from those animals are currently at the highest risk of infection. That includes poultry and dairy farmers and workers, veterinarians, animal health responders and workers handling raw milk or other contaminated products, such as food processors, slaughterhouse workers. and dairy laboratory workers.

"If you need to be near sick or dead animals, please wear appropriate PPE, including an N95 respirator and safety goggles," Dr. Hill said. "If you are exposed to sick or dead animals, monitor yourself for conjunctivitis and or a new respiratory illness," as these are symptoms that many people who've tested positive for the virus have experienced.

Are people with avian flu contagious?

Epidemiologists have yet to find direct evidence that H5N1 can spread from person to person. A study last fall followed nearly a hundred people who had close contact with an infected patient, and none of those close contacts ended up testing positive for the virus. However, so far three people have tested positive despite not having any obvious exposure to sick animals — meaning the possibility of their having caught the virus from another person can’t be ruled out.

Is the virus particularly dangerous for humans?

Right now, experts say the virus poses a low risk to humans. Most people who’ve tested positive for H5N1 have not gotten seriously ill and have made full recoveries. It can cause severe illness, however, especially in people with pre-existing conditions. In January, a patient in Louisiana became the first person in the U.S. to die from the virus.

Is there a vaccine?

The U.S. has a small stockpile of several different vaccines, each developed using a strain of H5N1 that was circulating in the early 2000s, said Dr. Angel Desai, professor of infectious disease at the UC Davis School of Medicine. None of the existing vaccines are currently commercially available, but a new mRNA vaccine against H5N1 is planned for a late-stage clinical trial.

The seasonal flu shot does not protect against H5N1, “but it’s still very important,” said Dr. Desai. For one thing, the more people are protected against the seasonal flu, the lower the odds that someone could catch that flu and H5N1 at the same time. “It may reduce the very rare chance of these influenza viruses mixing in a way that could make H5N1 more virulent to humans,” Desai said.

Could I get bird flu from my food?

“The short answer is no,” said Dr. Hill — though she notes one exception for raw milk. Infected poultry start to show symptoms quickly, and once farmers or tests spot a sick bird, the standard practice is to cull the whole flock before contaminated meat and eggs enter the food supply. The virus does transmit through cow’s milk, but most dairies pasteurize their milk before it’s sold, which inactivates the virus.

About raw milk: California dairies, including those that sell raw milk to consumers, are tested once a week, and follow a weeks-long quarantine program if any cows or milk test positive for H5N1. “But with samples a week apart, it’s still possible that raw milk with the virus can get into the food chain,” Hill said. “Raw milk does carry risks.”

Aside from the risks to human health, what else is at stake with this virus right now?

The risks to people of contracting H5N1 or getting seriously ill from it are both low, and UC scientists are among those keeping a watchful eye on the situation, ready to sound the alarm if that should change.

The effects of the virus are noticeable for many in the price of eggs. Poultry farmers in California have lost or culled 23 million birds in the past year. That means 150 million fewer eggs making it to supermarket shelves every week, a shortage that’s driving a $1.3 billion cost increase for consumers of California eggs since this time last year.

“But what we can say for certain already is that we have had unprecedented mass mortality events in our wild species,” Dr. Johnson said, with effects that will ripple throughout ecosystems around the world.