Part status symbol, part utility, people every year ditch still-functional devices for the newest, hottest model (sometimes literally, if the battery catches fire). The smartphone phenomenon is global, with an estimated 2.6 billion users around the world.

As smartphone users, we may be transfixed by our phones, but we rarely consider what’s inside them, where they came from or how they got to us. And perhaps we don’t want to know, because — let’s face it — our smartphones have been places.

Your worldly phone

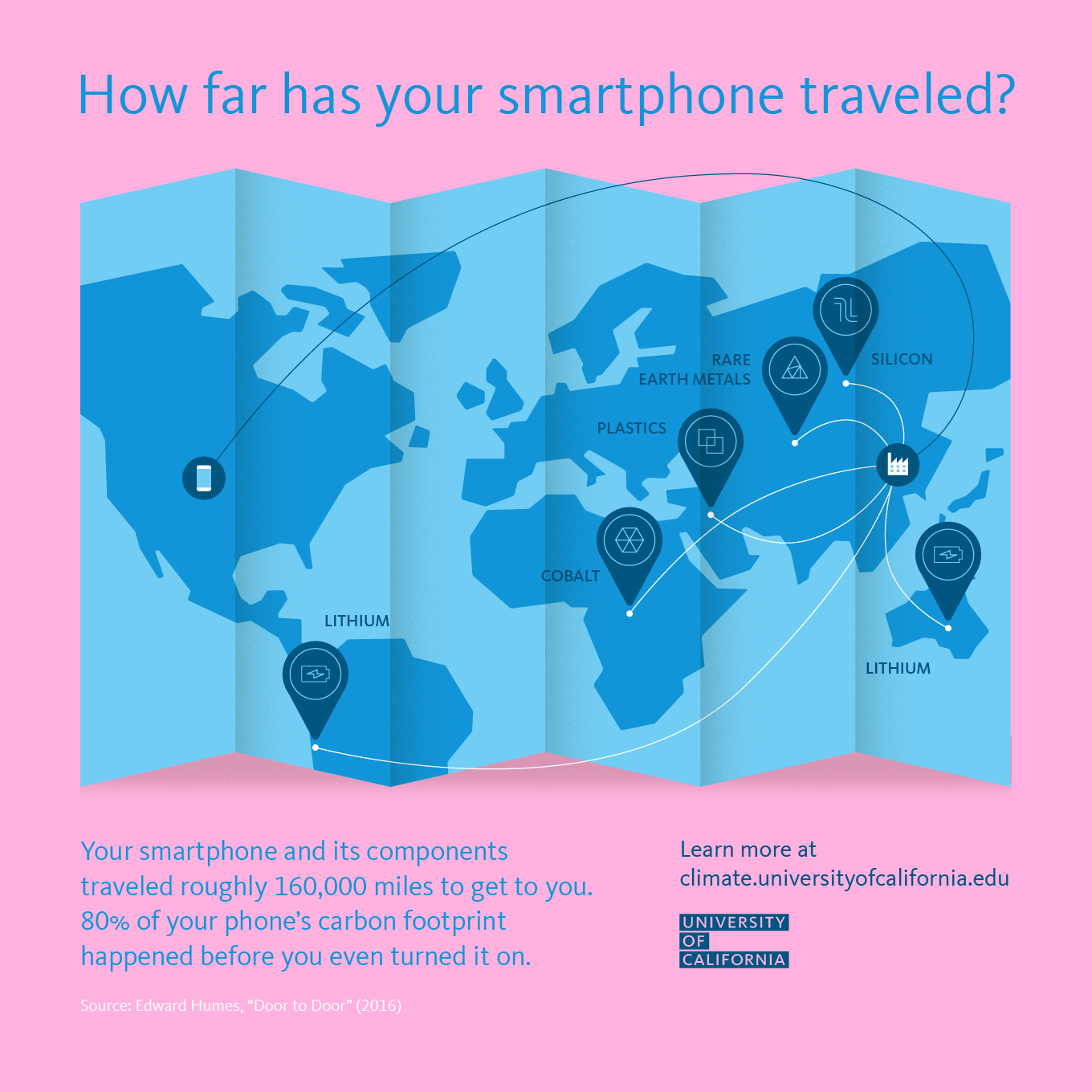

At least 70 elements on the periodic table can be found in smartphones, and they come from every corner of the globe. A mineral can be mined one place, refined elsewhere, built into a component somewhere else, and constructed into a device in an entirely different location. Edward Humes, author of the book “Door to Door: The Magnificent, Maddening, Mysterious World of Transportation,” determined that a fully constructed smartphone represents about 160,000 travel miles.

Roughly 80 percent of a phone’s climate impact happens before you even open the box.

The mining, refining and shipping of these materials takes energy and creates greenhouse emissions, contributing to global warming. Roughly 80 percent of a phone’s climate impact happens before you even open the box. Keep that in mind the next time you’re thinking of upgrading to a new phone with a slightly better camera.

Abundant silicon

The computer age as we know it wouldn’t be possible without silicon. Its properties as a semiconductor make the transistors that power microchips possible. Silicon is extremely abundant, making up over a quarter of Earth’s crust. In 2016 China produced over 4.5 billion metric tons of silicon. Since many smartphone components are made in China, Taiwan, Japan or Korea, the silicon doesn’t have to travel far. Russia was the second largest producer at 700 million metric tons, and the U.S. came in third at just under 400 million metric tons.

Rare earth elements

The 17 elements known as the “rare earth elements” — including neodymium and yttrium — are often found together in the same ore deposits. They’ve been crucial in making our suped-up and scaled-down technology possible. Despite the name, they’re not as rare as first thought. These elements are more than twice as abundant as copper and are used sparingly in smartphones. Yet uncertainty looms over their long-term supply. China currently provides more than 95 percent of the world’s rare earth elements.

Lithium

Powering a tiny computer with a big touch screen isn’t easy, especially when it all has to fit in your pocket. Lithium-ion batteries pack a lot of juice in a small package, allowing you to untether from a wall socket. Australia was the leading supplier of lithium in 2016, with Chile close behind.

Chile’s lithium is mined from beneath the Andes. Over millions of years, salts, lithium and other minerals leached into the ground beneath the mountains. Today, mining companies pump water underground to dissolve the salts, then flush the mineral-rich water to the surface to dry out for later collection.

Cobalt

The other major component of the lithium-ion battery is cobalt. Its journey to your cell phone is not a pretty one. Roughly 60 percent of cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where human rights abuses and mine safety issues have been a serious and ongoing problem. In many cases, the mineral is dug by hand in impoverished rural villages, where mining-related deaths and injuries are common. While many battery and electronics makers have acknowledged the problem and looked for alternatives, cobalt today comes not just with a carbon footprint, but a concerning human one as well.

Plastics

About 40 percent of the materials in a smartphone are plastic, particularly polycarbonate plastics. Though some phone makers opt for aluminum or glass bodies, plastics are a practical choice because they are durable and don’t interfere with radio signals (most phones end up in a plastic protective case either way). Plastics are derived from hydrocarbons like crude oil and coal. Currently Saudi Arabia and Russia are the top producers of crude oil.

Why are smartphones so disposable? Watch the following episode of Climate Lab to learn about what’s being done to clean up our favorite pieces of technology.