Pat Bailey, UC Davis

If you’ve always thought of a zebra’s stripes as offering some type of camouflaging protection against predators, it’s time to think again, suggest scientists at the University of Calgary and UC Davis.

Findings from their study were published Friday, Jan. 22, in the journal PLOS ONE.

“The most longstanding hypothesis for zebra striping is crypsis, or camouflaging, but until now the question has always been framed through human eyes,” said the study’s lead author, Amanda Melin, an assistant professor of biological anthropology at the University of Calgary, Canada.

“We, instead, carried out a series of calculations through which we were able to estimate the distances at which lions and spotted hyenas, as well as zebras, can see zebra stripes under daylight, twilight, or during a moonless night.

Melin conducted the study with Tim Caro, a UC Davis professor of wildlife biology. In earlier studies, Caro and other colleagues have provided evidence suggesting that the zebra’s stripes provide an evolutionary advantage by discouraging biting flies, which are natural pests of zebras.

In the new study, Melin, Caro and colleagues Donald Kline and Chihiro Hiramatsu found that stripes cannot be involved in allowing the zebras to blend in with the background of their environment or in breaking up the outline of the zebra, because at the point at which predators can see zebras stripes, they probably already have heard or smelled their zebra prey.

“The results from this new study provide no support at all for the idea that the zebra’s stripes provide some type of anti-predator camouflaging effect,” Caro said. “Instead, we reject this long-standing hypothesis that was debated by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace.”

New findings

To test the hypothesis that stripes camouflage the zebras against the backdrop of their natural environment, the researchers passed digital images taken in the field in Tanzania through spatial and color filters that simulated how the zebras would appear to their main predators — lions and spotted hyenas — as well as to other zebras.

They also measured the stripes’ widths and light contrast, or luminance, in order to estimate the maximum distance from which lions, spotted hyenas and zebras could detect stripes, using information about these animals’ visual capabilities.

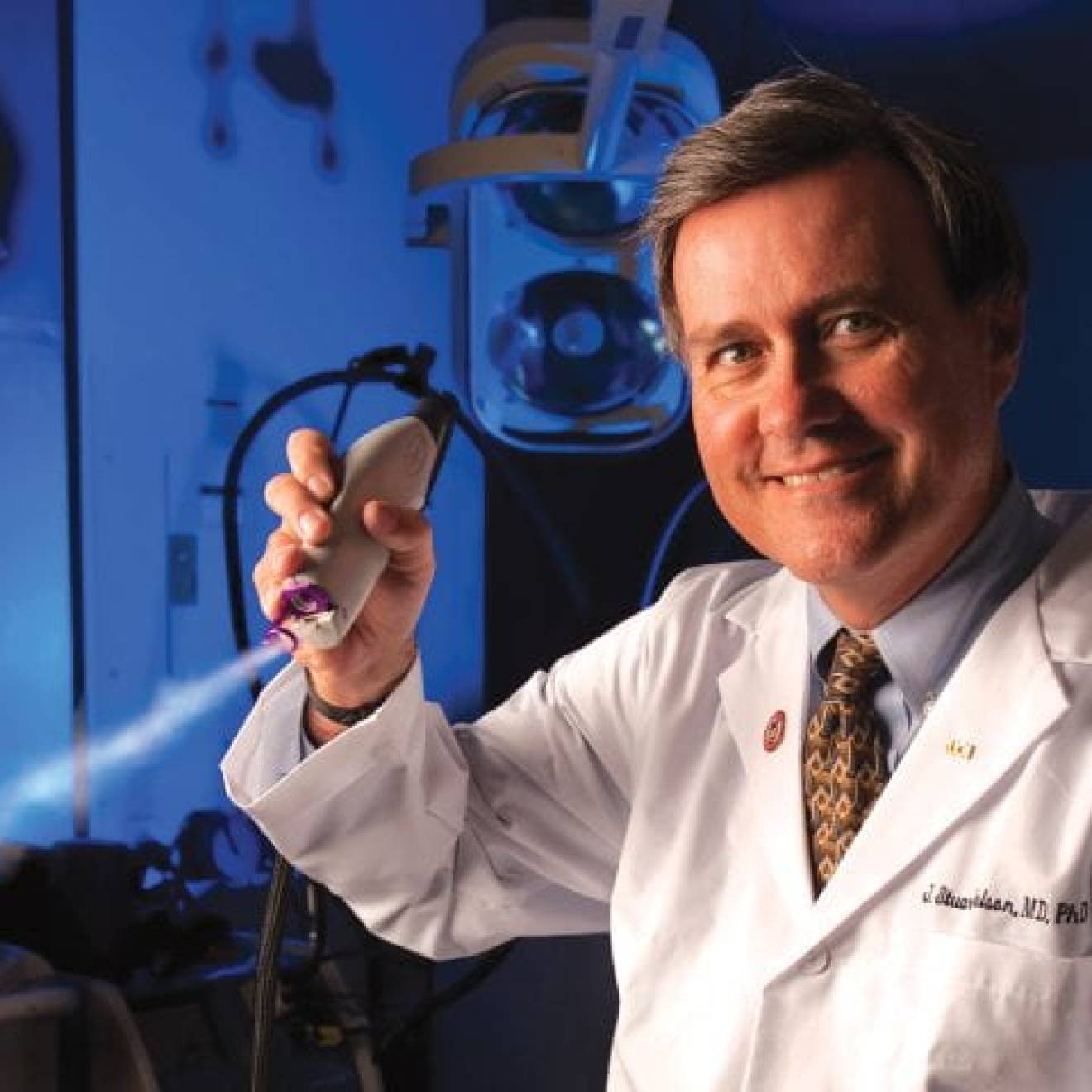

Credit: Tim Caro/UC Davis

They found that beyond 50 meters (about 164 feet) in daylight or 30 meters (about 98 feet) at twilight, when most predators hunt, stripes can be seen by humans but are hard for zebra predators to distinguish. And on moonless nights, the stripes are particularly difficult for all species to distinguish beyond 9 meters (about 29 feet.) This suggests that the stripes don’t provide camouflage in woodland areas, where it had earlier been theorized that black stripes mimicked tree trunks and white stripes blended in with shafts of light through the trees.

And in open, treeless habitats, where zebras tend to spend most of their time, the researchers found that lions could see the outline of striped zebras just as easily as they could see similar-sized prey with fairly solid-colored hides, such as waterbuck and topi, and the smaller impala. It had been earlier suggested that the striping might disrupt the outline of zebras on the plains, where they might otherwise be clearly visible to their predators.

Stripes also not for social purposes

In addition to discrediting the camouflaging hypothesis, the study did not yield evidence suggesting that the striping provides some type of social advantage by allowing other zebras to recognize each other at a distance.

While zebras can see stripes over somewhat further distances than their predators can, the researchers also noted that other species of animals that are closely related to the zebra are highly social and able to recognize other individuals of their species, despite having no striping to distinguish them.

Collaborators and funding

Collaborating with Melin and Caro were Donald W. Kline of the University of Calgary and Chihiro Hiramatsu of Kyushu University, Japan.

Funding for the study was provided by the Wenner Gren Foundation, the National Sciences and Research Council of Canada, the National Geographic Society and UC Davis.