Edward Lempinen, UC Berkeley

The COVID-19 pandemic is having a devastating economic and human impact on California child care centers, forcing hundreds of them to close while others remain open at the risk of illness to both children and staff, according to a new report from the University of California, Berkeley.

Among more than 950 preschools and in-home sites surveyed by the campus’s Center for the Study of Child Care Employment (CSCCE), fully 25 percent are closed. Among those that remain open, enrollments have plunged, and many owners are going into debt to keep their centers open for families who depend on continued child care, said the report released Wednesday, July 22.

“As a result of the pandemic, in California and in the whole country, we can see that child care is critically important to our economy and to parents who have to work,” said Lea Austin, CSCCE executive director. “But as child care collapses, so many other parts of our economy will be at risk.”

Bay Area Hispano Institute for Advancement Inc. (BAHIA) is a bilingual child development center founded in 1975 in West Berkeley. It has been closed since March, and executive director Beatriz Leyva-Cutler knows how such a loss can hurt her community.

If these closures multiply, Leyva-Cutler said, “low-income families will be the hardest hit. If the parents have to work outside the home, and without child care, they risk losing their jobs, which means more risk of hunger and homelessness.

“It also means that child care workers themselves face rising insecurity,” she added. “Our centers and our child care workers are essential to the economy, but the state and federal government have only scratched the surface to meet their needs. It feels like we’re invisible.”

Health or finances? Heartbreaking choices

At full strength, California’s centers and family homes care for close to a million children, according to CSCCE. Some 34,000 licensed child care facilities employ about 120,000 teachers and staff. Most are women of color, in positions that pay poverty-level wages for work that is highly important for a young child’s development and safety.

The center conducted its first survey on the impact of COVID-19 in April. In the latest, more extensive, survey, 953 respondents detailed a system in crisis, with families and care providers required to navigate complex issues of education, economics and health.

According to the report, many providers are fearful that they or their families will be infected with the virus — and that fear drives many closures. But others feel they can’t afford to shut down.

In that climate, the challenges are stark for programs that remain open:

- Eight-five percent reported reduced enrollment, with the average number of students cut roughly in half.

- Seventy-seven percent reported lost income, and significant numbers of providers reported they have missed rent or mortgage payments and used personal credit cards to cover expenses. Just over 40 percent said they have, at times, been unable to pay themselves.

- Even as revenues fall, 67 percent reported higher staffing costs to meet health and safety requirements.

- Eighty percent reported higher costs for sanitation and protective gear.

“This is just not going to be sustainable, long term,” said Austin. “We are seeing a collapse. It’s already begun, and I suspect it’s only going to be magnified as we go forward.”

‘We were hemorrhaging money’

Holly Gold spent the early years of her career in the nonprofit sector, working with young people. But 15 years ago, Gold founded the Rockridge Little School in Oakland, and it became the focal point for her deep community involvement.

As the school expanded to additional sites and enrolled more students, it won honors and a devoted local following. She paid her staff wages and benefits far above the California average.

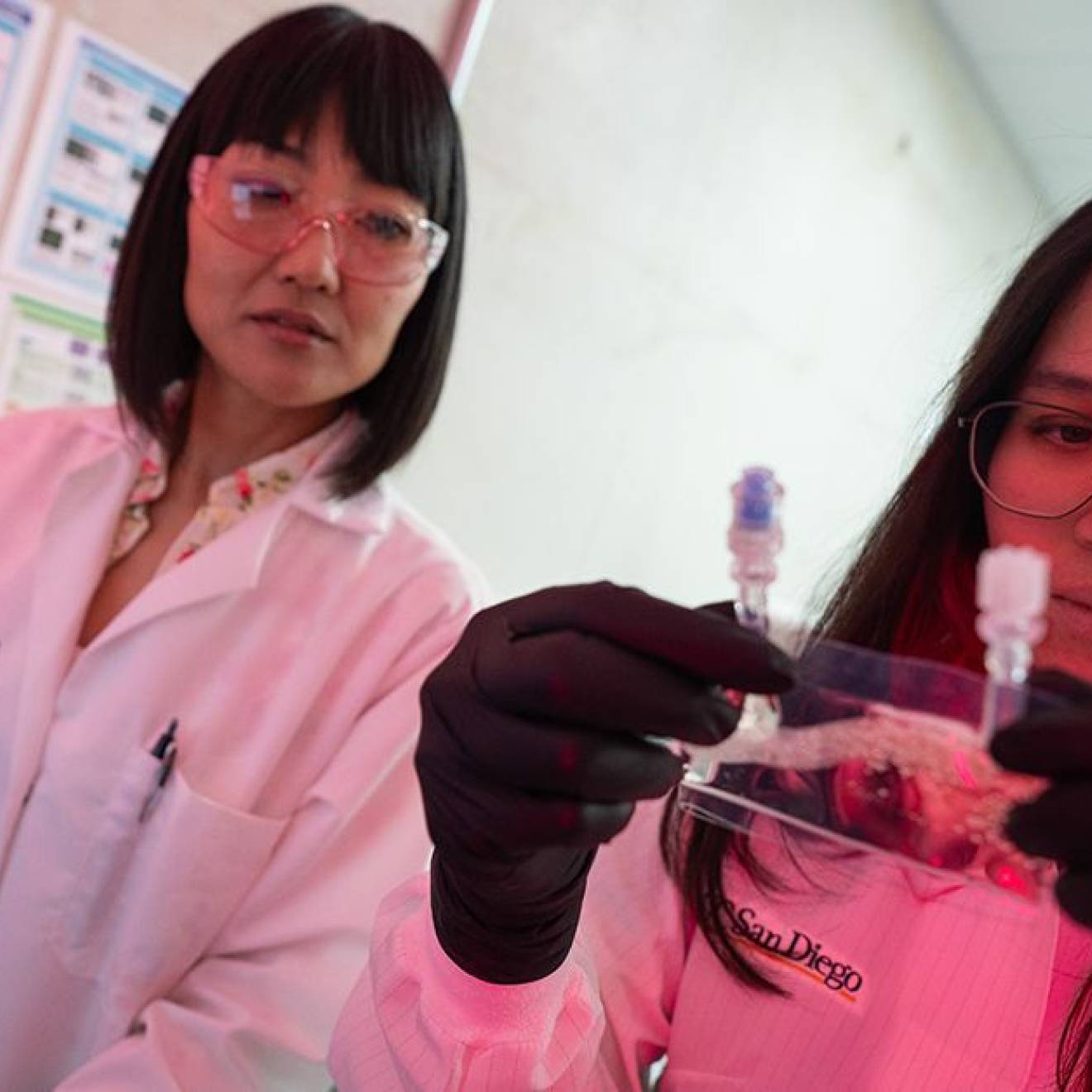

Credit: Brittany Hosea-Small/UC Berkeley

Gold funded her gradual expansion with tuition proceeds, but she recently tapped into her home mortgage and a loan from the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) to buy a building that needed repair. As long as the tuition funds flowed in, the numbers worked.

But then came COVID-19.

“In early March,” she recalled, “we were trying to figure out: What’s the right thing to do? How can we be open? I knew what it meant to close: complete devastation. You don’t even want to think about it. You just make decisions based on health.”

When Alameda County issued a stay-at-home order on March 15, Rockridge Little School closed.

At first, Gold continued to pay her staff their salaries and benefits. “But after a week,” she said, “we were hemorrhaging money.” She opted for layoffs, knowing that staff could get state unemployment benefits, plus the $600 weekly supplement offered under the federal CARES Act.

Weeks passed, the virus eased, and some parents urged her to reopen. Health officials signaled that, with careful management, it was safe. Gold set the date for early July and rehired some of her teachers. A number of families pledged to return.

But as the date approached, the virus surged. Some families backed out, leaving her with too many teachers. She shifted her plans, opening two sites rather than three.

Today, however, she’s in a jam: She’s behind on the rent. She owes on the SBA loan. She’s got to pay for the construction project. She received funds under the SBA’s Paycheck Protection Program, and she’s taken a personal loan. Still, the school’s expenses far exceed income.

“I’m just trying to figure it out,” she said. “We have families who say they’re coming back in September, so we’re trying to hold tight until then.”

‘I don’t know what to expect’

At BAHIA in West Berkeley, Beatriz Leyva-Cutler has a different baseline. The school owns its main building. A second building, for school-aged students, is owned by the city of Berkeley; as long as BAHIA provides government-subsidized care to low-income families, it pays only $1 a year in rent, plus maintenance.

There are up to 150 children in all, ages 2 to 10. Many are from working families, where parents have sectors such as construction or restaurants, while other youngsters’ parents are professionals, in fields such as architecture, law and nursing.

Credit: Brittany Hosea-Small/UC Berkeley

Leyva-Cutler has been there 40 years, and she knows BAHIA’s funds are always tight. Still, the pandemic has hit like a hurricane: The programs have been closed since March. The 30-plus teachers and staff are still employed — that was a condition of continued state aid during the pandemic. But the halls are silent, and weeds are growing on the playground.

Typically, BAHIA receives hundreds of thousands of dollars in tuition, but those funds are gone, for now. The year’s projected $1.8 million in revenue is down to $1 million.

Leyva-Cutler, who also serves on the Berkeley Unified School District Board of Education, has been working 60 hours or more every week to keep things afloat. “We’ve done the small business loan and the emergency disaster impact loan,” she explained. “We’re refinancing one of our buildings. We have to do whatever we can to stay operational.”

There were plans to reopen on July 6. But a teacher’s husband tested positive for the virus, then her daughter, and then the teacher herself.

The center’s reopening was pushed to July 27.

The urgent need for government support

The CSCCE report makes clear that, across California, many preschools and in-home care centers are facing their own versions of this crisis. But there’s a consensus that the state and federal governments need to do more.

If California’s child care system is strong, experts say, it can play a crucial role in eventual economic recovery. But if the system is crippled, recovery efforts will suffer. So will children and their families.

“This pandemic has brought to light to how important child care is,” said Leyva-Cutler. “But, unfortunately, we’ve gotten used to the fact that this care is undervalued and under-appreciated.”

Leyva-Cutler proposes that state agencies waive some regulations, temporarily, for centers that have had positive audits in the past. Gold, meanwhile, advocates an infusion of state funding — not just for state-subsidized centers, but for private centers, too.

Austin said the state of Vermont has done something similar: a “stabilization” fund that provides support to both state-subsidized and private day care.

For now, however, Leyva-Cutler, Gold and thousands of other child care providers in California are struggling to manage their way through deep uncertainty. They’re facing a new world: More risk, smaller classes, new rules for wearing masks, social distancing and sanitation. It will be, said Gold, “a very different way of teaching.”

For many centers, economics will compound this uncertainty, testing their creativity, patience — and survival.

See the full report, “California Child Care in Crisis.”