Jonathan Riggs, UCLA

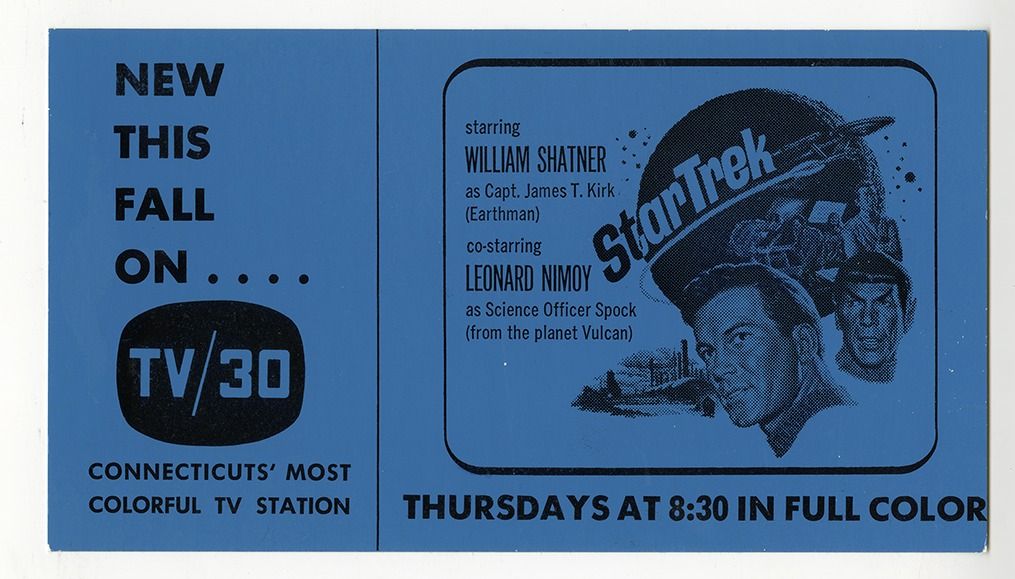

Since its television debut on Sept. 8, 1966, “Star Trek” has not only entertained millions of fans but also inspired generations of viewers to think about, study and even travel into space.

Perhaps UCLA’s most prominent connection to the Star Trek galaxy: For decades, the campus has been home to an extensive archive of materials related to the show that was donated by none other than Gene Roddenberry, the creator of the original series. And the newest connection? The UCLA Nimoy Theater, which opens Sept. 17, is named for one of the franchise’s stars, Leonard Nimoy, and his wife, the writer-actor-director Susan Nimoy, whose philanthropy helped UCLA purchase the building.

To help celebrate Star Trek Day, held each year on the anniversary of the premiere, we asked two UCLA scholars — Smadar Naoz, professor of physics and astronomy, and Doug Johnson, a UCLA Library Special Collections archivist — to discuss how the show influenced them and how concepts from the show have (or haven’t) translated into life on Earth in the 21st century.

“Science fiction is really a trigger for curiosity,” Naoz said. “Many things that were presented in ‘Star Trek’ came to be, like the colorful microtapes the crew used became floppy disks in real life. And that’s not all: Cell phones, portable medical scanners, tablet computers. So many things today echo what the show imagined.”

What first sparked your interest in “Star Trek”?

Smadar Naoz: For me, it started when I was around 5, in Israel in the 1980s. We had an old black-and-white TV, and my mom used to watch the show and read the subtitles for us because we didn’t know English. It opened a whole new world of excitement for me, just wanting to understand what is out there.

Doug Johnson: I was a kid in the 1970s and I don’t remember ever not liking it. I am Japanese, and one thing I really loved about it was George Takei as Sulu. He and Jack Soo, as Nick Yemana on “Barney Miller,” were my two television role models. I loved that feeling of representation.

Speaking of representation, the show’s portrayal of women was progressive at times — but not always.

Naoz: In the original series, you see the women in tiny skirts and in supporting roles. However, in the original pilot, the women wore pants and had equal roles. The character Number One, for example, was the first officer, which is pretty impressive. But one can imagine that there was some pushback to seeing women in such powerful roles back in the 1960s.

Johnson: It’s very telling of the times that the network didn’t like the Number One character, so she got demoted to be Nurse Chapel for the rest of the series.

Naoz: It shows how even when imagining the future, it can be challenging to escape the present.

Let’s talk about some concepts that defined “Star Trek” and how they echo in the real world, starting with the spacecraft itself. How does reality overlap with the idea of the Enterprise supporting a full-time crew while traveling the galaxy indefinitely?

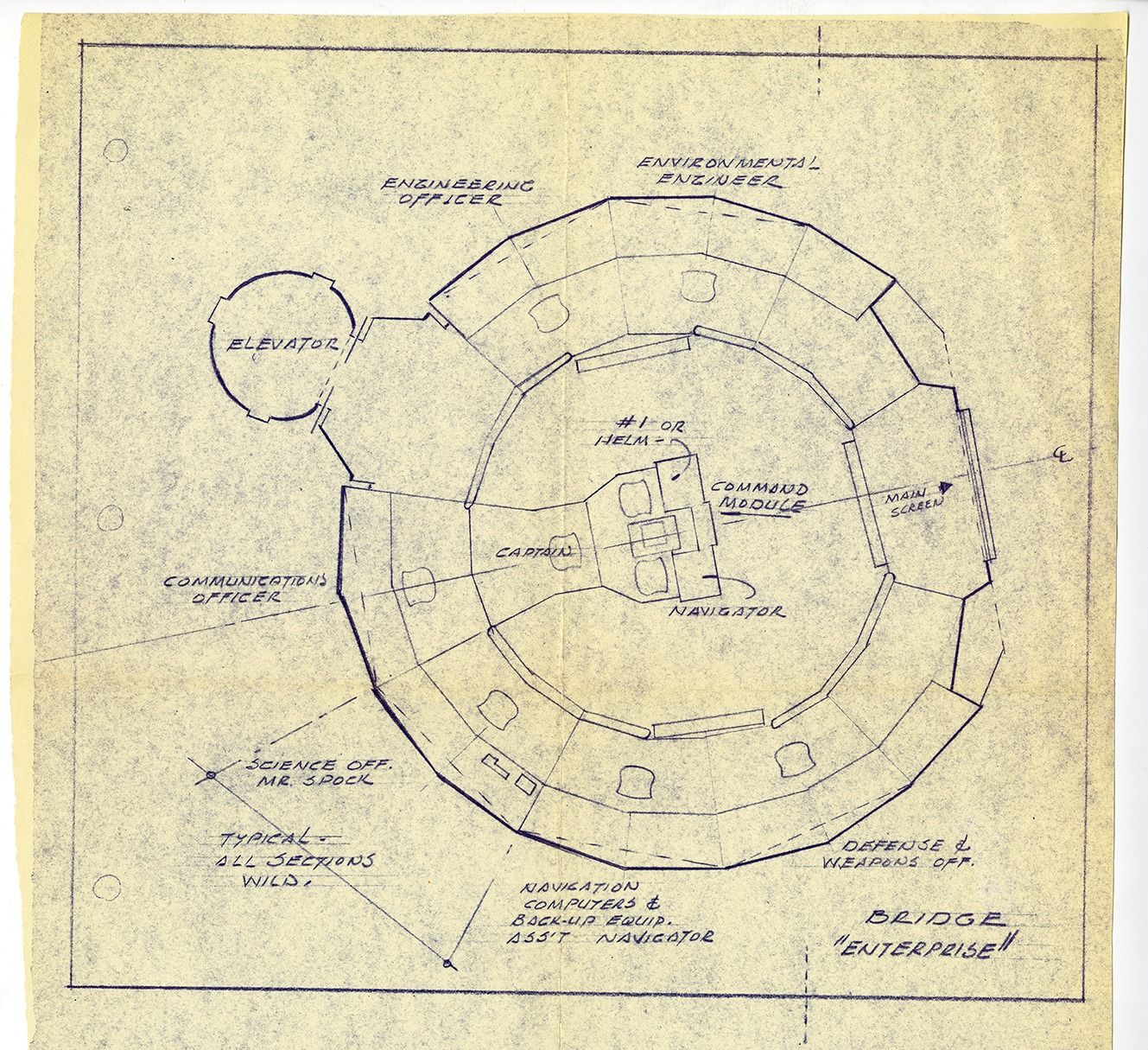

Johnson: Gene Roddenberry initially imagined the Enterprise like “Wagon Train” to the stars — a caravan of people that would stop at various planets, see what was going on and then move on to the next one.

Naoz: We’re not even close to having a real-life Enterprise. The closest sci fi extrapolation to our near future I can think of is the series “The Expanse,” which was on the Syfy network and Amazon. It imagines a reality that could potentially happen in decades.

What about phasers?

Naoz: Scientifically, phasers are problematic. They’re supposed to be this concentrated beam of light visible to all, but science tells us that people viewing them from the side wouldn’t be able to see it.

Johnson: I love that they could have “phasers on stun” instead of just shooting holes in people, which goes along with the generally pacifist message of “Star Trek.”

What about the idea of “beaming” people up?

Naoz: We all wish for instantaneous travel like that, right? Of course, there is a problem with the impossibility of moving faster than light. In reality, the closest thing to “beaming” is quantum entanglement, which is not exactly the same.

And contact with extraterrestrials?

Johnson: I love the movie “Star Trek: First Contact” because aliens run into us instead of the other way around. That makes sense to me. As a planet, we’re probably kind of infants developmentally so it seems as if it would be much more likely that a more advanced civilization would find us first.

Naoz: The show presents extraterrestrials in ways that we can understand and have some interactions with. But if they do exist in real life, they may be so different that we would not even recognize them as such. Evolution is such a chaotic system with a few convergences — like many species on Earth evolved to have eyes because of our specific sun — that it’s fascinating trying to imagine how completely different other life forms could be beyond what we know here.

Finally, how about the idea that humanity will eventually achieve harmony?

Johnson: There’s a concept in the original series called IDIC — infinite diversity in infinite combinations. It’s an attitude of acceptance of plurality, that differences do not weaken us. Coincidentally, the concept of IDIC was introduced in an episode called “Is There in Truth No Beauty?” which was written by a UCLA librarian, Jean Lisette Aroeste, who just sent it in as a spec script.

Naoz: The episode centers around a woman who cannot see, but it’s highlighted in a positive way. That’s one thing I really like about “Star Trek” in general: that diversity is not just related to race and gender, but also to physical states, disabilities and neurodiversity.

But I wonder if some of the enduring attraction of “Star Trek” for so many people is that it presents a future in which there is something good in us as human beings. We need to work very hard to be able to live up to the expectations of that world, but I want to believe that one day we’ll prove to be better than we are right now.