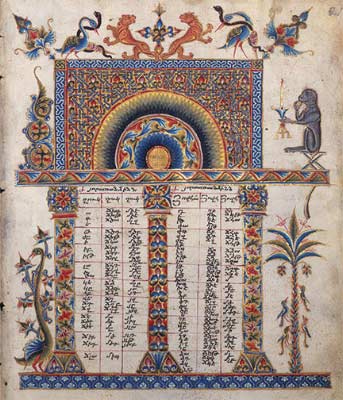

Meg Sullivan, UCLA

Credit: Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library

For the past 40 years, Maryanne Horowitz has tried to attend at least one event a month at UCLA's Center for Medieval Renaissance Studies even as she climbed the tenure ladder, raised three children and taught up to three history courses at a time.

The feat would be impressive enough had this specialist in the French Renaissance been on faculty at UCLA, but she’s not. Horowitz is a longtime professor at Occidental College in Eagle Rock, and, like a moth to a flame, she has been drawn to the center's wide array of lectures, seminars and conferences in her field since 1973.

"It's put me in the know," said Horowitz of her association with the center.

And she's not alone. Scholars from all over the world flock to this beloved institution that has become a scholarly time machine that transports inquiring minds to points between 400 A.D. and the mid-17th century. Since its founding, the center has become one of the top two sites in North America for scholars to meet and discuss the structure of Dante's comedy, medieval lyrics or Byzantine Greece, all topics on its calendar of events.

"Other universities have centers for medieval and Renaissance studies, but they rarely have the institutional permanence or mount the kind of programs that UCLA can," said Richard Unger, a professor of medieval history at the University of British Columbia and president of the Medieval Academy of America, the field's premiere scholarly association. "There will be one or two or three people who get a program going, and they'll retire and the program will fade. But at UCLA, the center has gone from strength to strength."

In fact, the "med ren center" or CMRS — as its followers refer to it — was the first center in the humanities within the College of Letters and Science and may be the longest-running center of its kind anywhere. This weekend, it wraps up a year's worth of programming celebrating its 50th anniversary with a conference examining trends in the field.

"It's a time for us to celebrate our past achievements and reflect on where we're heading in the future," said center director Massimo Ciavolella, a professor of Italian and the Franklin D. Murphy chair of Italian Renaissance studies.

It began in 1963 after more than 60 UCLA faculty members endorsed a proposal calling for "a major research center implementing and enlarging the new conception of medieval and Renaissance studies, and their close alliance with classical scholarship." Such a center, they noted, "is needed in this country but nowhere seems in prospect save at UCLA."

Centers bring together faculty from different disciplines not to offer courses to students, but to share the latest research and scholarship and to critique and encourage each other’s work. Centers also bring lecturers and visiting faculty to campus and fund research efforts beyond the means or scope of a single department.

By the late 1960s, the center’s first director, Lynn White Jr., a Stanford-educated historian who specialized in medieval technology, had done such a good job of creating a buzz that scholars were being lured here from the East.

A pamphlet from CMRS was what first caught Henry A. Kelly’s attention before he left Harvard to join the English faculty in 1967. "I was looking for something congenial and interdisciplinary, and the list of scholars on the brochure seemed to fit the bill," he said.

In 1970, CMRS established two journals. Kelly, who later became a center director, remembers having to "struggle and beat the bushes" for submissions to Viator, a pioneer in publishing scholarship from both the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Meanwhile, Comitatus, a journal for graduate students, managed only to attract UCLA contributors. Today, both are among the premiere journals in the field. Viator's only rivals are published by national societies, and they're limited by the periods on which they focus. Comitatus now attracts articles from recent Ph.D.s as well as students from all over the world.

By 1972, the center's reputation had grown to such an extent that the Medieval Academy of America decided to hold its annual convention at UCLA, the first held west of Chicago.

The center’s second director, the late UCLA English professor William Matthews, served as the editor of an 11-volume edition of the late 17th-century diary of Samuel Pepys, an English naval administrator and member of Parliament. Matthews' edition of the diary is still revered for Pepys' eyewitness accounts of such historic events as the Great Plague of London, the Second Dutch War and the Great Fire of London. The center continues to honor its Pepys connection with an annual banquet and lecture.

The center's Golden Age, most agree, occurred in the 1980s under its third director, the late Fredi Chiappelli. The nationally recognized Renaissance scholar spearheaded research and planning for an ambitious commemoration of the 1992 quincentennial of Christopher Columbus' voyage to America. Some 14 years after Chiappelli's death, the center published the 13-volume Repertorium Columbianum, featuring the most significant documents about Columbus and his place in his time.

Early on, CMRS decided to break with tradition. While other academic units devoted to the Middle Ages and Renaissance have tended to be humanities-based, CMRS embraced a wide range of disciplines. Its 121 scholars hail not just from English, the European languages, art history and history, but from architecture and medicine as well as the sciences. "It was interdisciplinary before that became a watchword," said Michael Allen, a professor emeritus of English who twice served as CMRS director.

For example, on Feb. 7, the center will host a daylong symposium on Galileo Galilei. Among the leading scholars from around the world who will explore interconnections between Galileo's scientific breakthroughs and his love of music and poetry will be a Mount Holyoke College mathematician/physicist who wrote the critically acclaimed "Galileo's Muse: Renaissance Mathematics and the Arts" (Harvard University Press, 2011). Also coming is an Indiana University authority on the Italian Baroque who will trace Galileo's fingerprints in modern science fiction.

The center has also developed an extraordinary geographic reach. While many of its peer institutions focus on Europe, UCLA's center has always been much more inclusive, embracing faculty doing work in Near Eastern Languages and Culture and Latin America. Once considered iconoclastic, both foci are now widely accepted in the field.

"They've seen which way the wind is blowing and play a role in driving trends in the field," Unger said of those who have charted the center’s course. More recently, the center has included scholars active in Asian studies. Last year, the center hosted talks by three UCLA faculty in Asian studies, including Humanities Dean David Schaberg.

Still, with an aging faculty and continuing funding challenges, the center has faced hurdles. In recent years, many graduate students have opted to study contemporary issues rather than medieval or Renaissance topics, Ciavolella said. Moreover, fewer undergraduates now enroll at UCLA with backgrounds in European and classical languages.

"If you don't have these skills at the high school level, it becomes difficult as undergraduates to enter the field," Ciavolella said.

But the tide appears to be turning for the center. In April, CMRS will host a joint meeting of the Medieval Academy of America and the Medieval Association in the Pacific, drawing some 400 scholars from all around the world to more than 50 sessions on such topics as "Carolingian Voices" and "Crusade Encounters."

And the ranks of medieval and Renaissance scholars at UCLA are growing again. Last year the history department signed on Jessica Goldberg, a medievalist who specializes in the economic and legal institutions of the Mediterranean basin, Christian Europe and the Islamic world. Arvind Thomas, who specializes in Middle English and early modern literature, joined the English faculty last summer.

College administrators will soon launch a search for a faculty member to helm a major grant in Renaissance Latin. The $700,000 grant is expected to establish UCLA as a leader for Renaissance Latin, which served as the lingua franca of intellectuals in medicine, law, literature and the arts from the 14th to the 17th centuries.

"We have a strong tradition at UCLA in medieval and Renaissance studies," Schaberg said. "It began to wane a bit, but now we're reinvesting again."