UCLA

With help from elderly survivors of the World War II internment camps, the UCLA Asian American Studies Center has launched the Suyama Project to gather and make available online evidence of resistance among Japanese Americans who were forcibly removed from their homes and sent to camps by the federal government, shattering the myth of the “quiet Americans” who silently accepted their fate without question.

For nearly a year, researchers at the center have been finding, scanning and then returning to their owners letters, diaries, photographs, newspaper clippings, artwork and unpublished manuscripts to bring to light stories of resistance that the War Relocation Authority (WRA) — the civilian agency created by the U.S. government to manage the internment camps where 120,000 were imprisoned — and others tried to minimize or suppress at the time, say faculty leaders of the project. (The Asian American Studies Center believes it’s not accurate to use the term “internment camps” and prefers “U.S. concentration camps.” See related sidebar about the ongoing debate over terminology.)

Propagated by the WRA, the government and the Japanese American Citizens League during World War II, the myth of the complacent captives has been embedded in newspaper stories, books, movies and many history books, said Lane Ryo Hirabayashi, the George and Sakaya Aratani Professor of Asian American Studies at UCLA and one of five UCLA professors who serve as advisors to the Suyama Project.

“It wasn’t a matter of people being ‘quiet;’ rather, it had to do with people being intimidated, with being silenced. We’ve had some moving testimony in this regard,” Hirabayashi said.

Chronicles of resistance

Among those whose histories are featured on the Suyama website are conscientious objectors, draft resisters, renunciants (those citizens who, under pressure, renounced their U.S. citizenships) and the No-Nos — those who were branded as disloyal and sent to prison for answering “no” to two controversial, poorly worded questions on a loyalty questionnaire issued by the U.S. Army.

“Elements within the Japanese American community also tried to erase these stories in the hope that mainstream Americans would more readily accept Japanese Americans as patriotic and loyal,” Hirabayashi explained. “It took the contemporary redress movement and the eventual passage of the Civil Liberties Act to open people up to the many stories of resistance” that were once considered taboo to talk about.

Even after the war, these acts of resistance were mere background noise to the postwar narrative about Japanese Americans who served courageously in the military, including members of the celebrated 442nd Regimental Combat Team that was made up almost entirely of Japanese American soldiers. Ironically, 1,500 of them were drafted directly from the internment camps.

“Of course, focusing on the veterans and the sacrifices they made was important,” said David Yoo, professor and director of the UCLA Asian American Studies Center. “But scholars now see that the experiences of Japanese Americans during World War ll were more diverse than that, and that you need to think about the community as a whole, and not just one segment of it.”

In one sense, Yoo said, those who resisted were demonstrating a form of loyalty to America. “It’s not always popular to resist, but in many ways it’s also exercising a very important part of what it means to be an American.”

The only university-based archive focused on both small- and large-scale acts of resistance, the project is being funded by an endowment established by an anonymous donor and is named after Dr. Eji Suyama, a physician and distinguished veteran of the 442nd. Suyama understood that those who resisted the government’s efforts to imprison them were also courageous. So after the war, he became one of the few voices in the community to advocate for them in numerous letters to newspapers, Yoo said.

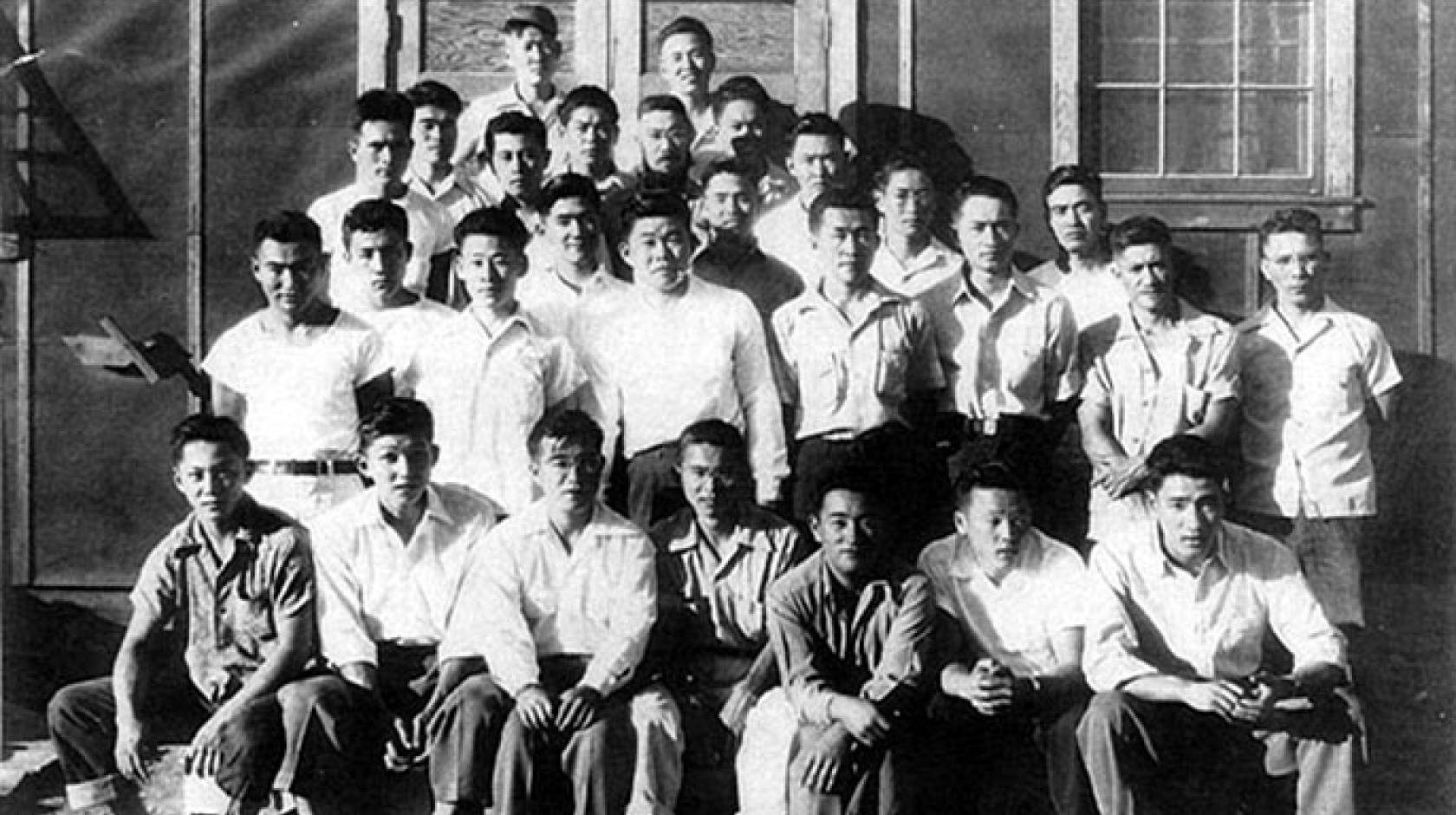

Among those dissidents were the men of Block 42 at the Tule Lake camp. They were arrested by camp administrators and sent to prison after they refused to answer a loyalty questionnaire whose wording and title were confusing to them, according to the website. The War Department and the FBI later informed Tule Lake administrators that refusing to answer the loyalty questionnaire was neither a violation of the Selective Service Act nor the Espionage Act and did not carry a $10,000 fine and/or 20 years in jail, as camp administrators had threatened. But this information did not become public until decades later.

There were riots, sit-down strikes, work stoppages and other episodes of unrest at the camps, much of it to protest deplorable living conditions there. “The strikes early on in Poston and Tule Lake were major acts of resistance,” Hirabayashi said. “The military was called in to restore order, and people were shot.”

Researchers are also documenting the actions of “everyday people who were doing things on the sly to let the WRA personnel know that they weren’t being fooled,” Hirabayashi said. In Poston, for example, someone chalked the words “Jap Prison” on the tar paper wall of the camp schoolhouse. Under cover of darkness, people "borrowed" wood from the camps’ main lumber supplies to build makeshift furniture, another act of everyday resistance.

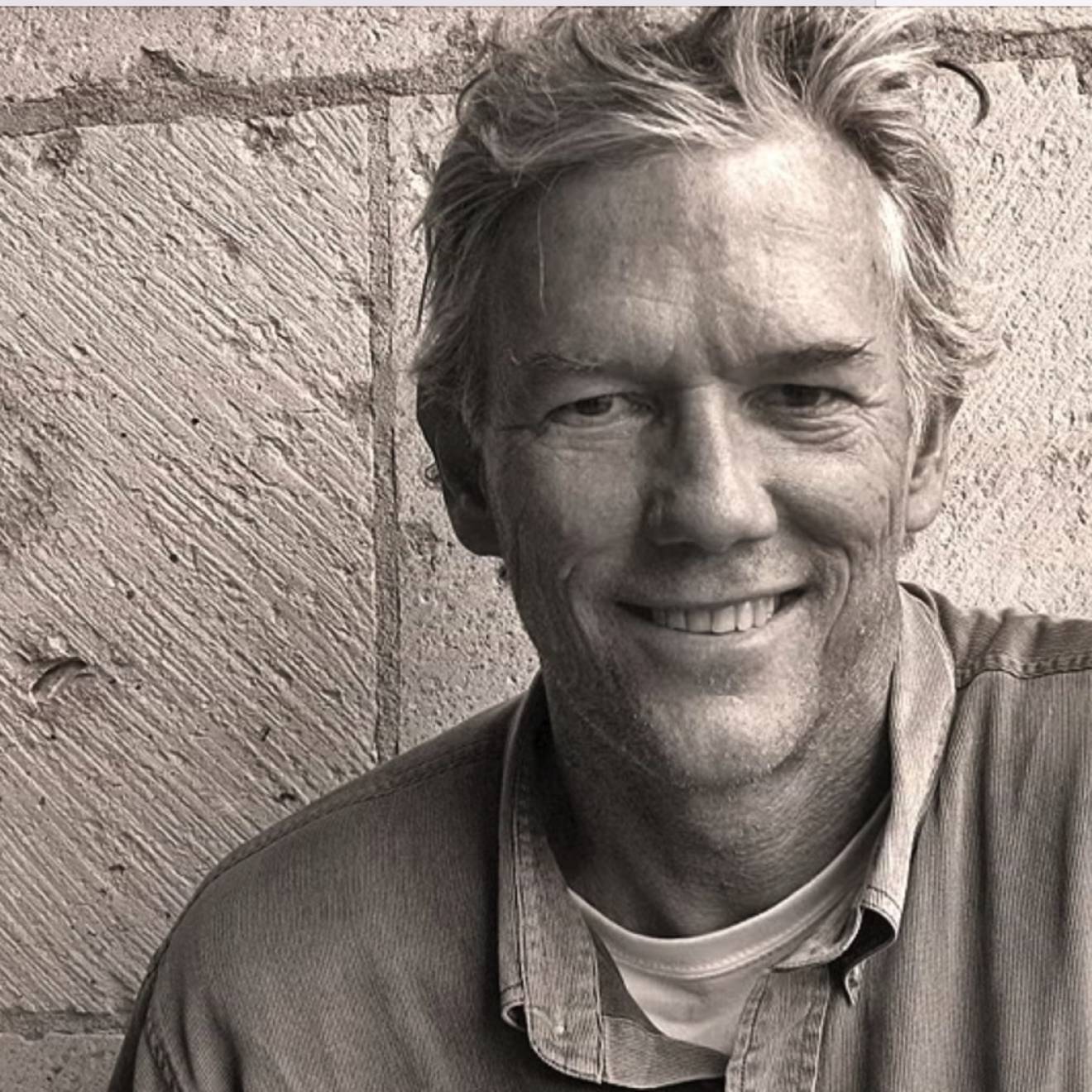

Among the more prominent of the “boat rockers,” as dissidents were labeled by Japanese American civic leaders, was Gordon Hirabayashi, professor Hirabayashi’s uncle, who called the incarceration of American citizens of Japanese descent discriminatory and unconstitutional. The son of Japanese immigrants, he was a 24-year-old senior at the University of Washington when the government ordered him and his family to board a bus bound for a camp.

When Gordon Hirabayashi protested, he was convicted and imprisoned. After a 40-year crusade to clear his name, he won a landmark court case against the U.S. government. His efforts as a civil rights advocate helped convince Congress to pass legislation in 1988 apologizing for the government’s actions and paying more than $1 billion in reparations to former internees. In 2012, President Obama awarded Gordon Hirabayashi the Presidential Medal of Freedom three months after his death.

Getting the word out

To inform the Japanese American community about the project, collect data and provide a forum for resisters to talk about their experiences — many in public for the first time — the Asian American Studies Center has held a few community forums. Since many of the survivors are elderly, the time to gather their stories and eyewitness accounts is now, Yoo said.

So far, the project has been welcomed by Japanese Americans whom the center has approached, Yoo said. In the coming academic year, outreach events are being planned for Seattle and other locations.

At one presentation, an elderly survivor of the Poston camp, accompanied by his daughter, gave an emotionally charged account of his own acts of resistance to what was going on at the camp.

“Someone asked [his daughter] if she had ever heard her father talk about his deep objections to the abuse that the WRA authorities meted out in Poston,” Hirabayashi recalled. “Tears started rolling down her face as she said, ‘No, I’ve never heard any of this before.’

“I learn something at every forum I go to,” the scholar said.