Jessica Wolf, UCLA

Modern Judeo-Christian rhetoric and imagery purports that Satan is an evil opponent to all that is good and godly — a literal opponent of God.

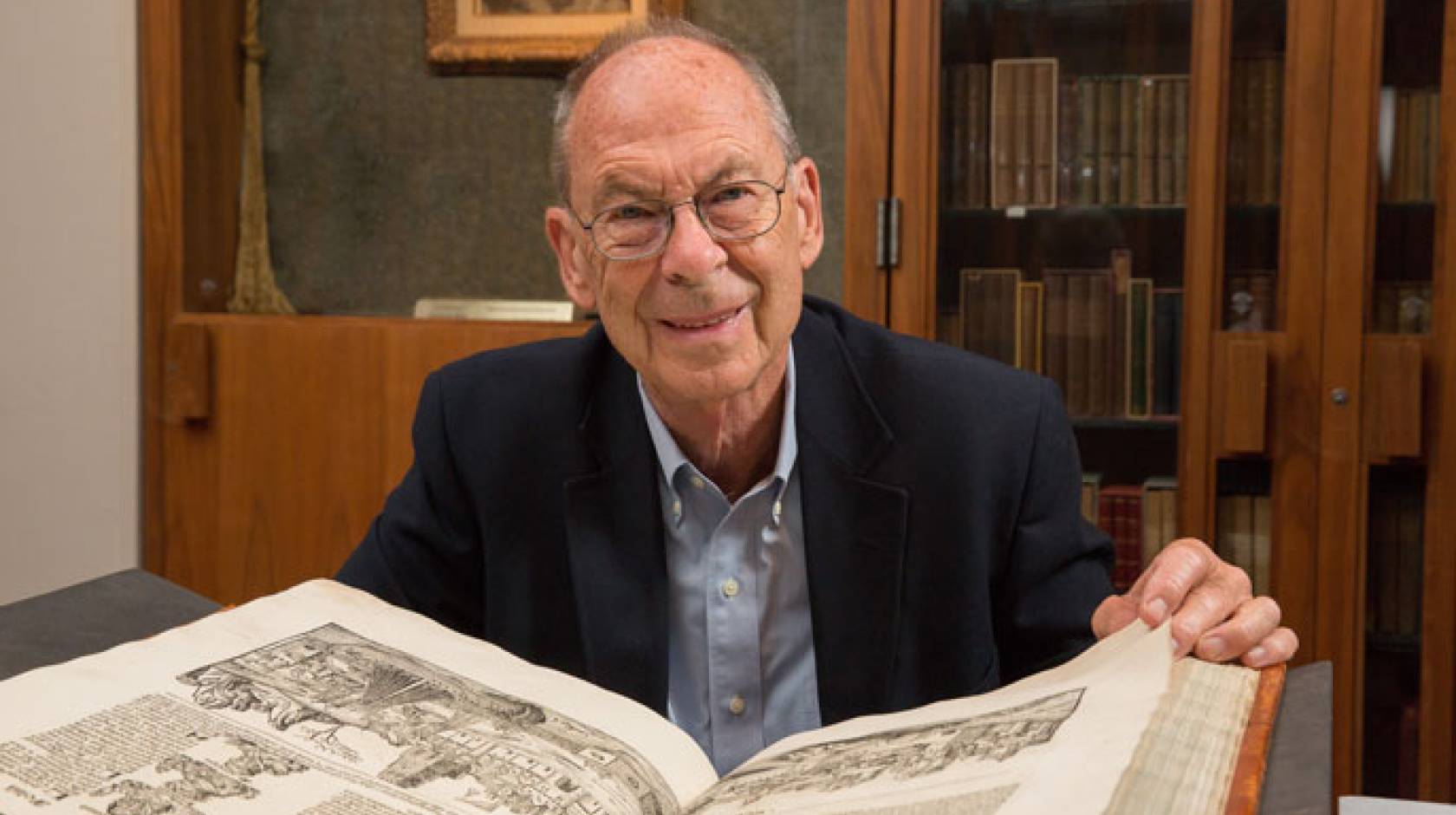

But that characterization doesn’t hold up under critical scrutiny of the Bible, says Henry Ansgar Kelly, UCLA distinguished research professor of English and one of the world’s leading experts on Satan. His 2006 book “Satan: A Biography” was a top seller for Cambridge University Press.

His latest book, “Satan in the Bible, God’s Minister of Justice,” combs through all the relevant passages of the Old and New testaments, tracking evidence of stories of the devil we think we know. The early appearances of the word “satan,” when literally translated from Hebrew, simply means “adversary.” None of the passages that use the word refer to an inherently evil spirit, Kelly said.

“A frequent assumption about Satan is not only that he is as bad as can be, but also that he has always been considered this bad,” Kelly said. “I have been researching and writing about the devil for over 50 years now, and have been making many of the same points without really being able to get across my main point, that no matter when we have heard about Satan and his nature and history, and activities, most them are not to be found in the Bible, where he is a much different person.”

Looking back through the Old and New testaments, Kelly said it becomes clear that Satan, no matter what we may think of him or imagine him to be now, was not originally presented as the implacable enemy of God, but rather God’s heavenly assistant in dealing with human beings.

As Kelly contends, Satan is more like an old-guard authority figure committed to the status quo and as such is an obstructer of social welfare or change — such as the ideas preached by Jesus. Satan is looking out for God’s interests and is distrustful of humans, but that doesn’t necessarily make him “evil” per se.

“In our government, he would correspond to the head of the department of justice, the attorney general,” Kelly said.

How the image of Satan evolved

In his book, Kelly looks at the ways in which later interpretations of and additions to the Old and New testaments, as well as post-biblical texts — some from as late as the 10th century A.D. — led to an evolving image of Satan.

Even the notion that Satan assumed the guise of a serpent to play a role in the Judeo-Christian idea of “original sin” when Adam and Eve ate of the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden doesn’t hold up under a critical lens, Kelly said. While the story of Adam and Eve leads off the Book of Genesis, there is no reference to it in the rest of the Old Testament, which indicates that it was a late insertion. And in the original story there was certainly no connection of the serpent with Satan.

“I conclude that Satan was not associated with Adam until the second century A.D., when the Samaritan philosopher Justin Martyr identified him with the serpent,” Kelly said. “I like to say that Justin was a good Samaritan but a bad philosopher. He was also, more importantly, a bad linguist. The reason he was convinced that the serpent was Satan was that he believed Jesus said so.”

Kelly outlines that Martyr came to his conclusion by way of folk etymology. The Hebrew word “satan” had given way to Aramaic “satanah,” which in the Greek New Testament is rendered as “satanas.” Martyr thought that when Jesus named the devil “Satanas,” he was calling him “Satah Nahash,” which means “apostate serpent” in Hebrew.

Martyr found verification of this idea in the Book of Wisdom in the Greek Old Testament, which says that death entered the world through the envy of a devil (“diabolos”), but that text was referencing Cain, the first killer, who murdered his brother Abel.

Fostering research about religious ideals and practices is very important, since religion is such an integral aspect of human culture, said Kelly, who studied as a Jesuit in the 1960s. He has been teaching at UCLA for 50 years and said he is grateful for the existence of UCLA’s Center for the Study of Religion.

“One should think that studying and teaching about the Bible’s formation, content, and influence would be a very big part of university education,” Kelly said, “but partially because of misguided ideas of the separation of church and state very few people are exposed to sophisticated examinations of the Bible, and most are left with childhood instruction or vague allusions they have picked up on their own.”

Christian and Jewish scholars tend to agree it’s best to read the Bible along with notes that explain the scholarship behind the text — something like the “New Oxford Annotated Bible,” he said.

“The Bible, and especially the New Testament, is arguably the most influential book in the whole of human history,” Kelly said. ‘But most people don’t have a clue about the huge amount of scholarship that has gone into explaining it.”