UC Newsroom

If Andrea Ghez had listened to her critics, one of the galaxy’s greatest mysteries might yet remain unsolved.

The UCLA astronomer won the 2020 Nobel Prize in physics for proving the existence of a supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. Like every other scientist who’s reached the pinnacle of their field, Ghez has overcome a lot of skepticism along the way — after all, questions are the driver of the scientific method. What is science if not the process of putting your elegant theories through the meat grinder of rigorous testing and review?

But Ghez also faced down doubts that had nothing to do with the laws of physics. “At every stage, someone has always said no, you can’t do this because you’re a girl,” she recalls. “I got very used to ignoring when people said I couldn’t do something.”

In winning the Nobel Prize, Ghez joined one of the smallest clubs in science. Of the 749 people who’ve won the prize in a scientific field — physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, or economics — just 29 have been women. And of that small group, nearly 1 in 4 have ties to the University of California. This Women’s History Month, we’re honoring UC’s seven women Nobelists who’ve overcome the odds and changed the world.

This Women’s History Month, we’re honoring UC’s seven women Nobelists who’ve overcome the odds and changed the world.

Elinor Ostrom, UCLA, Economic Sciences, 2009

The first woman to win The Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, UCLA alumna Elinor Ostrom was honored in 2009 for her analysis of economic governance and how common resources can be successfully managed by the people who use them. Her work bucked the conventional wisdom that common property is best regulated by government or privatized. Looking at the interaction of people and ecosystems, Ostrom conducted numerous field studies of how people in small communities managed shared natural resources like fish stocks, pastures, forests and groundwater basins. She found that local, collective management often yielded better results than outside intervention. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences noted that her work “advanced economic governance research from the fringe to the forefront of scientific attention.”

Ostrom commented on her win in an interview with the academy: “Having lived through an era where I was thinking of going to graduate school and was strongly discouraged because I would never be able to do anything but teach in a city college … [laughs] Life has changed!” She received her bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees from UCLA. A faculty member at University of Indiana Bloomington for 47 years, Ostrom died of pancreatic cancer in 2012, continuing her work until her last day.

Andrea Ghez, UCLA, Physics, 2020

For decades, the question of what lies at the center of our galaxy was the subject of fervent scientific debate. Andrea Ghez, a UCLA professor of physics, astronomy and astrophysics, and Reinhard Genzel, a UC Berkeley professor emeritus of physics and astronomy, shared a 2020 Nobel Prize in physics for providing a provocative answer: a supermassive black hole that is four million times the mass of our sun. Ghez’s work has opened a new approach to studying black holes, one that she is using to understand the physics of gravity near a black hole and the role that black holes play in the formation and evolution of galaxies. “Her group’s discoveries are a continuing sequence of stepping stones that go further and deeper into new science,” says fellow UCLA professor Mark Morris.

One of the world’s leading experts in observational astrophysics, Ghez created and heads UCLA’s Galactic Center Group. “There were times when people didn’t believe our approaches would work,” reflects Ghez. “I was pretty well trained by then to believe in myself.” She is the fourth woman ever to be awarded the Nobel Prize in physics.

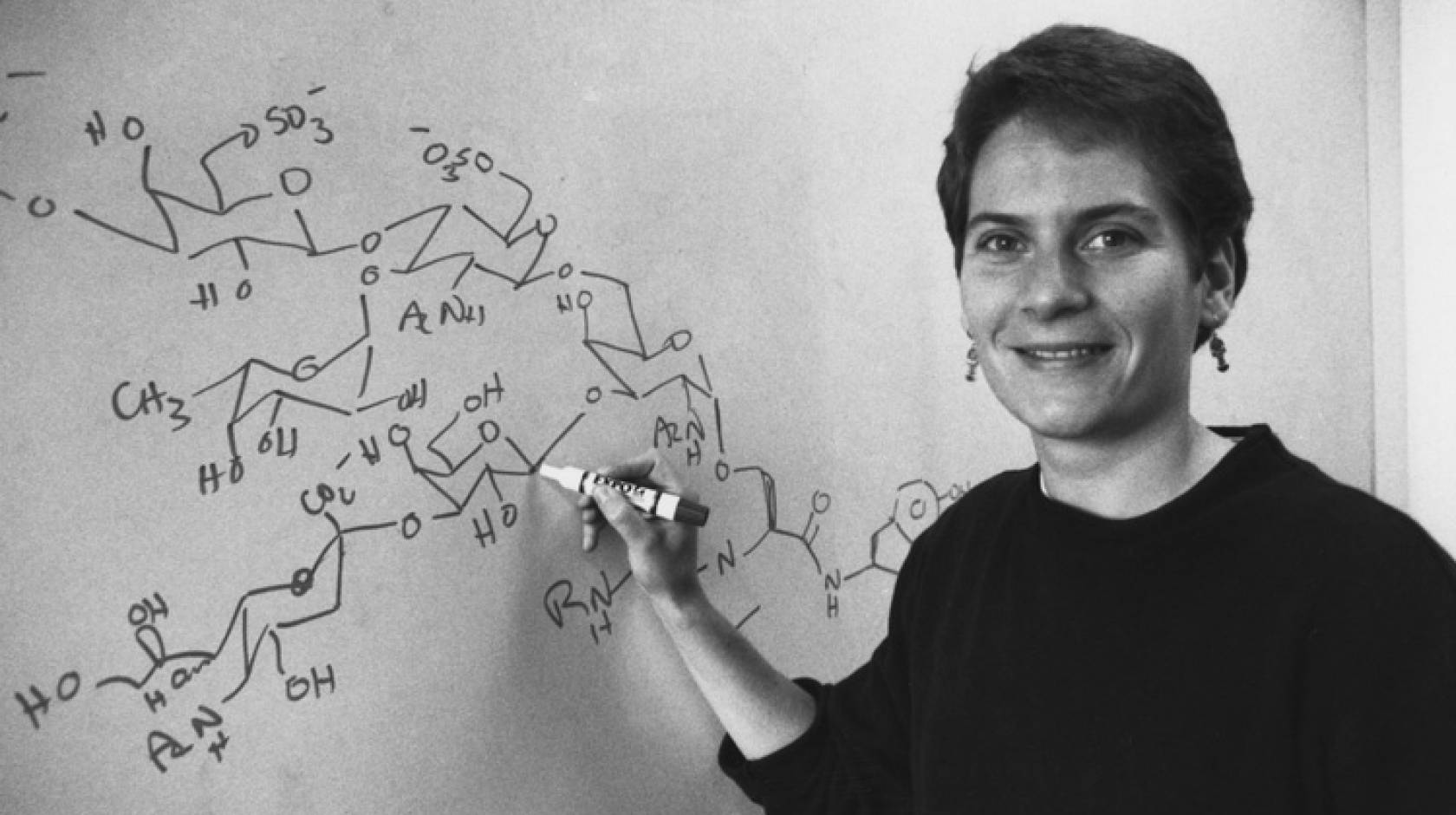

Carolyn Bertozzi, UC Berkeley, Chemistry, 2022

UC Berkeley alumna Carolyn Bertozzi was awarded the 2022 Nobel Prize in chemistry for developing bioorthogonal chemistry, in which chemical reactions can be performed inside living organisms (including humans) without disrupting normal cell chemistry. Bertozzi’s work built on the “click chemistry” developed by her Nobel Prize co-winners K. Barry Sharpless and Morten Meldal. Among many other applications, bioorthogonal reactions can be used in cancer diagnosis and the targeted delivery of cancer drugs.

Bertozzi worked at UC Berkeley for 19 years, developing the chemical biology techniques for which she received the Nobel Prize. She earned her Ph.D. from Cal in 1993, returned in 1996 as a chemistry faculty and Berkeley Lab member, and became the first director of the Berkeley Lab’s Molecular Foundry, a cutting-edge nanoscience research facility. She left in 2015 for Stanford’s Safran ChEM-H Institute, which she still leads today. “Carolyn Bertozzi is a true trailblazer in chemical biology,” said Doug Clark, dean of the UC Berkeley College of Chemistry. “Her lab is among the most prolific in the field, consistently producing innovative and enabling chemical approaches, inspired by organic synthesis, for the study of complex biomolecules in living cells. Carolyn’s work and spirit embody what is best about the scientific tradition and history of the College of Chemistry and of UC Berkeley.”