Harry Mok, UC Newsroom

UC Santa Cruz professor Dan Costa and his colleagues are pioneers in the use of satellite tags to monitor the migration of elephant seals.

Over the years, they’ve compiled one of the richest datasets available for any marine mammal species, unlocking the mysteries of elephant seal behavior and discovering their astonishing ability to dive more than a mile below the ocean's surface to search for squid and other food.

"For the first time, we can truly say that we know what the elephant seal population is doing," said Costa, an ecologist.

In another first, the satellite tags have also created a bounty of temperature readings from the deep ocean.

An ocean of climate data

The data — nearly 1.2 million temperature measurements collected over more than a decade — is now an important part of the World Ocean Database, a tool for scientists exploring climate change.

Oceanographers are using the temperature readings to analyze how climate change is affecting marine ecosystems and to assess how well elephant seals and other sea life will be able to adapt.

The World Ocean Database contains nearly 13 million temperature profiles and 6 million salinity measurements. It is administered by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration’s data center, and is made freely available to researchers everywhere.

"It's a powerful tool being used by scientists around the globe to study how changes in the ocean can impact weather and climate," said Tim Boyer, an oceanographer with NOAA’s National Oceanographic Data Center.

Adapting to climate change

Along with elephant seals, Costa’s team has also tagged and tracked 23 species of fish, turtles, seabirds, sharks and marine mammals during the past decade.

The information provides insights into their behavior, but also helps researchers predict how vulnerable different species could be to dramatic changes in the ecosystem — changes that scientists believe are likely in the coming decades as a result of climate change.

Some animals will be more successful than others in adapting to change or shifting locations to follow their ideal habitat, according to a recent study conducted by a group of international scientists as part of a working group at UC Santa Barbara's National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis.

Researchers analyzed 50 years worth of data related to sea surface and land temperatures and created a global map of where species are likely to succeed or fail to keep up with changing climate.

While some species can easily move, others may find that their preferred climate disappears due to terrain barriers such as a coastline.

Helping species survive

“One of the greatest challenges these days is how to help species survive in the face of climate change,” said Ben Halpern, a professor at UC Santa Barbara's Bren School of Environmental Science & Management and a study co-author. “The maps we produced offer a key tool for helping guide these decisions.

"For example, where species are likely to face climate traps, we will need to explore less traditional actions, such as assisted migration, where people help move species past barriers into their preferred environment.”

What is increasingly clear is that no corner of the world's oceans is likely to be untouched by climate change.

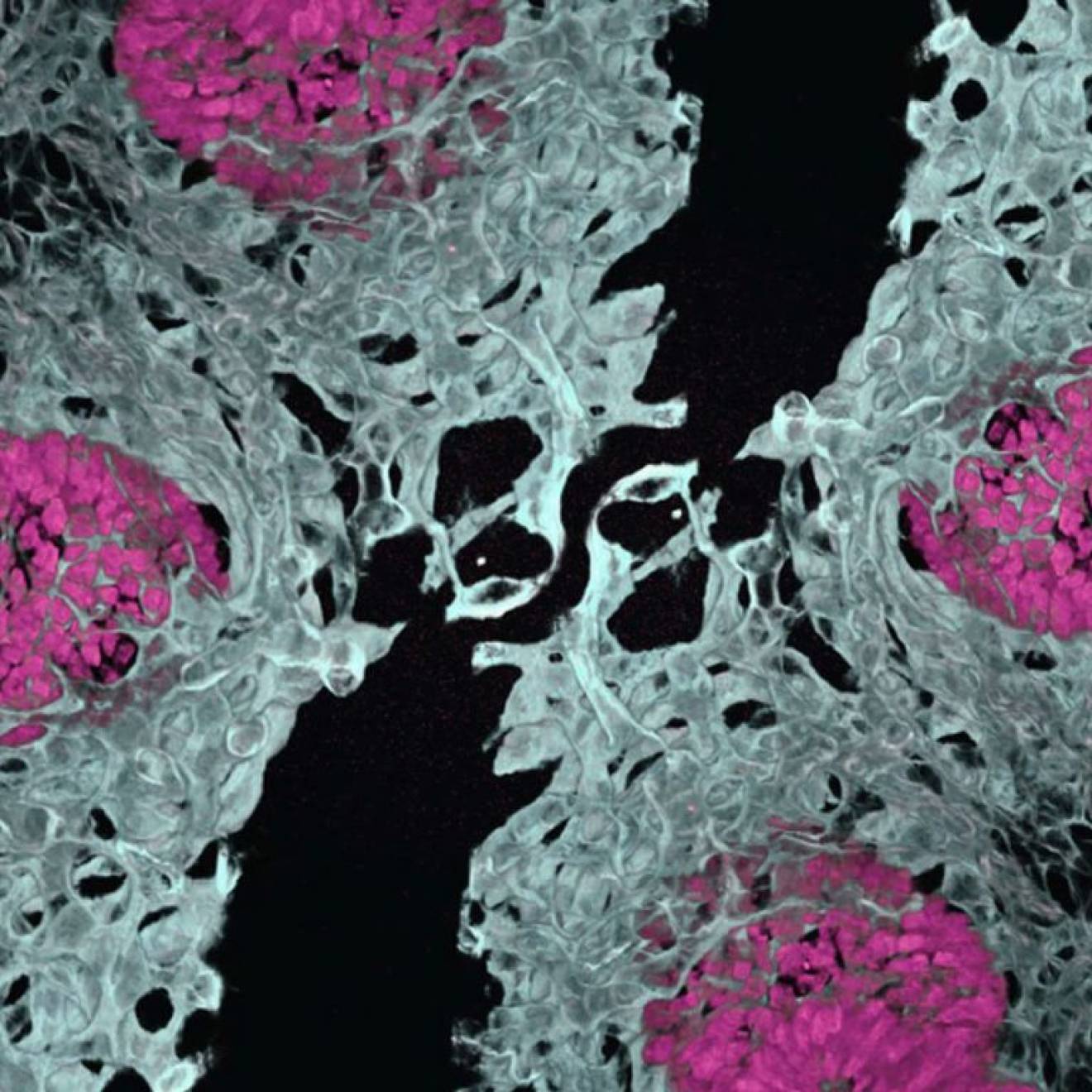

In a far-reaching study co-authored by Lisa Levin and Ben Grupe of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, scientists found that by 2100 a host of biochemical changes — triggered by climate change — will cascade through marine habitats and organisms.

The study describes how manmade greenhouse gas emissions are warming the oceans, increasing acidification and reducing oxygen levels, all of which will change marine habitats and could kill off many species of sea life.

Major disruptions in ocean habitats

As a consequence, there could be major disruptions to fisheries, tourism and other industries that rely on healthy oceans. The study shows that some 470 million to 870 million of the world’s poorest people rely on the sea for food and their livelihoods.

“Because many deep-sea ecosystems are so stable, even small changes in temperature, oxygen, and pH may lower the resilience of deep-sea communities,” said Levin, director of the Center for Marine Biodiversity and Conservation at Scripps. “This is a growing concern as humans extract more resources and create more disturbances in the deep ocean.”

A new stewardship ethos

Levin, along with others, is calling for a new “stewardship mentality” that extends across countries, economic sectors, and disciplines.

Nothing less will protect the future health and integrity of the deep ocean.

“We need international cooperation to develop and oversee deep-ocean stewardship,” Levin said. “We also need multiple sources of research funding that can help provide the scientific information that we need to manage the deep sea.”