UCLA

While war rages in Syria, that country's people can still experience the culture and history of the region’s Mesopotamian roots through an exhibit made possible by a Kurdish nonprofit organization and UCLA archaeologist Giorgio Buccellati.

“The local people, on their own initiative, put the exhibit together, and that strikes me as extraordinary,” said Buccellati, a professor emeritus of Near Eastern languages and culture and history. “It’s an extremely dangerous situation, and the very fact that they put it together is a miracle.” Buccellati is director of the UCLA Cotsen Institute of Archaeology’s Mesopotamia Area Lab as well as the L.A.-based International Institute for Mesopotamian Area Studies.

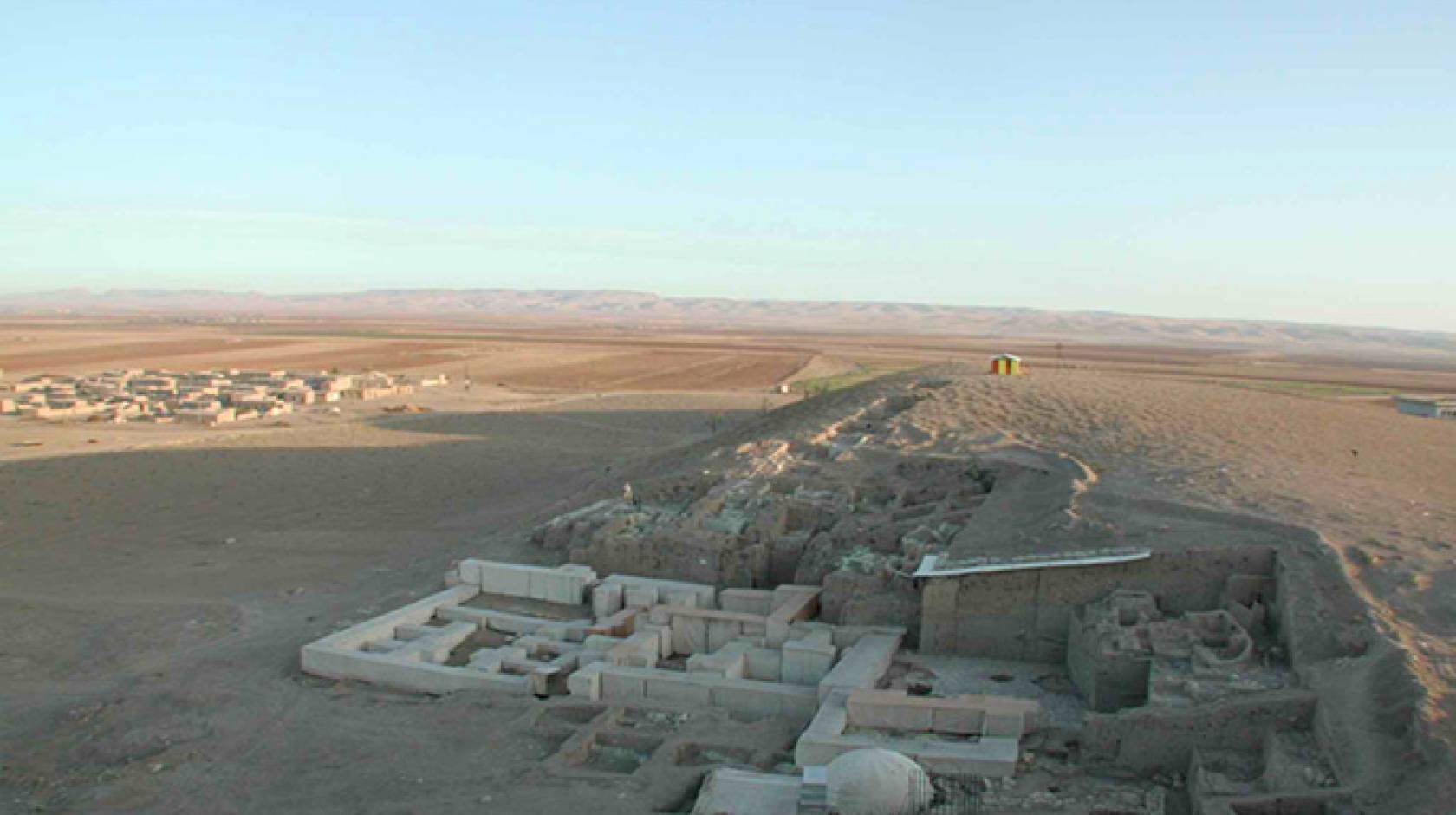

Two decades ago, Buccellati and a team that included his wife, Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati, uncovered Urkesh, one of the largest archaeological sites from the third millennium B.C. in the Near East. The team excavated the site continuously until 2011, when civil war in the region escalated to a level that pushed the team — by then among the last foreign archaeologists in the country — out of Syria. Plans were also stalled to open an archaeological park in Urkesh, which would have enabled citizens to learn more about their Mesopotamian roots, while also stimulating the economy of the rural area.

However, history is still being told in “The Revival of Life in Urkesh/Tell Mozan," an exhibition of photos and other visuals related to the Urkesh site. Through collaborative efforts by the Subartu Cultural Association — which promotes Kurdish culture through exhibits of local artists, lectures and children’s events — and Buccellati’s Tell Mozan/Urkesh Archaeological Project, the exhibition has traveled around the area since Dec. 30, 2014.

“The Revival of Life in Urkesh/Tell Mozan" features 19 panels depicting the excavation of the site, as well as the historical interpretation of what has been uncovered there. The exhibition opened in Qamishli, a northeastern Syrian city on the border with Turkey, and has traveled to three small towns. On Feb. 24 it will arrive in Amouda, the township where the Urkesh excavation site is located, and it will later travel to two additional locations.

Urkesh housed monumental public buildings, including a large temple. It was the main religious center, as well as a political capital, of the region in Mesopotamia.

“The identification of Urkesh is analogous to knowing that Rome is in central Italy and then finding Rome,” Buccellati said at the time of the city’s discovery.

Although the war in Syria prohibits Buccellati from returning to Urkesh, the site is protected by six Syrian villagers who focus on maintaining the city’s mud brick walls from the elements.The villagers, with whom he is in regular contact, receive support from UCLA, which recently contributed $50,000 to this effort.

"The ancient history of Syria is one that, in many respects, transcends the ethnic divisions because there are no more people of that ancient ethnic group. The people we are studying preceded all of them so they are a way of linking to a shared past," Buccellati said in a UCLA Newsroom interview in May 2014. "The archaeology and history of a country can help to overcome barriers."