Suzanne Leigh, UCSF

A rear-ender in which the driver’s head slams against the steering wheel or a helmet-to-helmet tussle with an opponent on the football field may increase one’s risk for Parkinson’s disease if concussion results, say researchers from UCSF and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

In their study, which publishes April 18, 2018, in the online issue of Neurology®, the researchers looked at the prevalence of Parkinson’s among close to one-third of a million veterans, comparing its incidence in those who had experienced a traumatic brain injury — such as concussion — with those who had not. They found that veterans who had had concussion faced a 56 percent increased risk for Parkinson’s.

Concussion was defined as loss of consciousness for up to 30 minutes, altered consciousness or amnesia for up to 24 hours.

Results relevant to more than vets

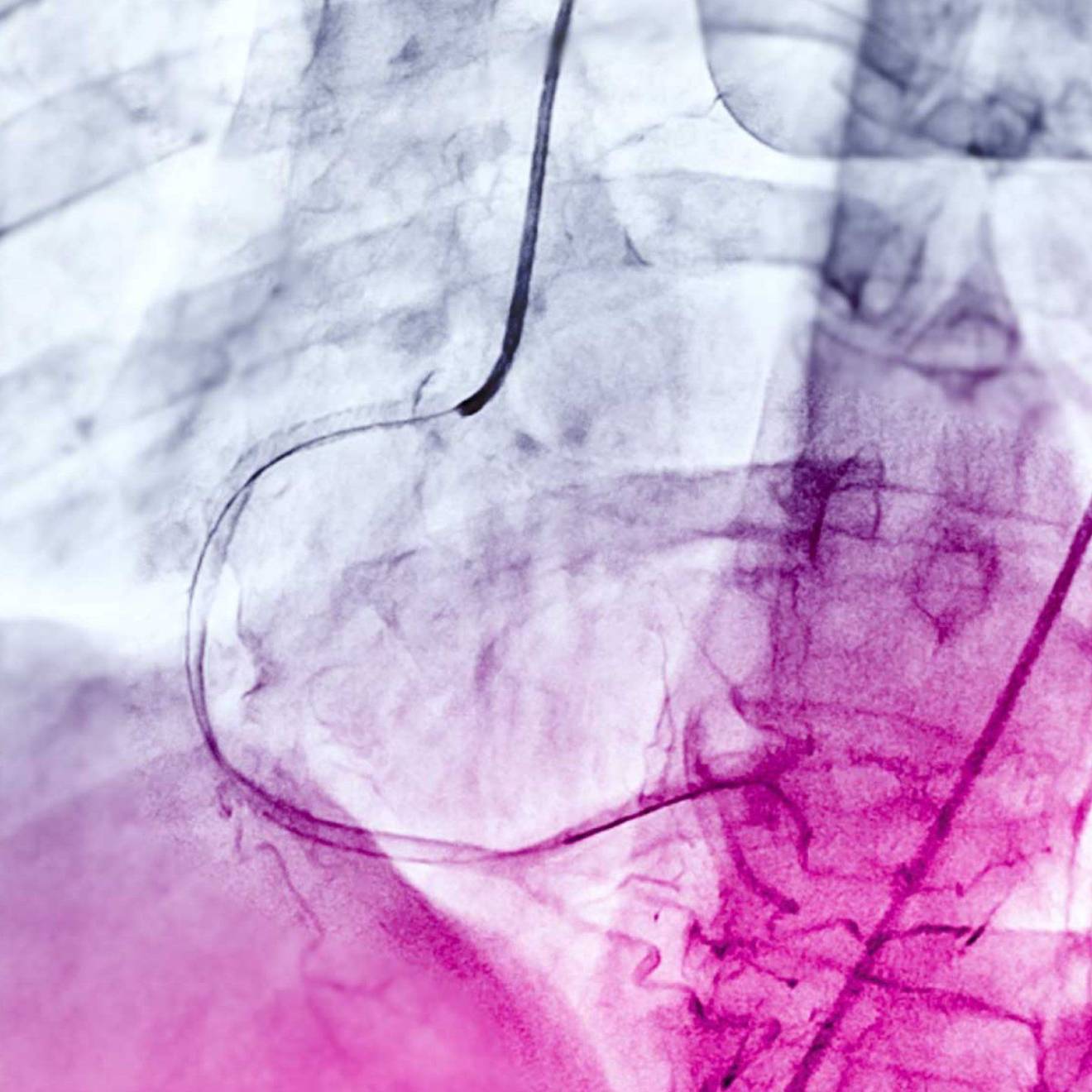

Credit: UCSF

“While the participants had all served in the active military, many if not most of the traumatic brain injuries had been acquired during civilian life,” said senior author and principal investigator Kristine Yaffe, M.D., of the UCSF departments of neurology, psychiatry, medicine, and epidemiology and biostatistics. “As such, we believe it has important implications for the general population.”

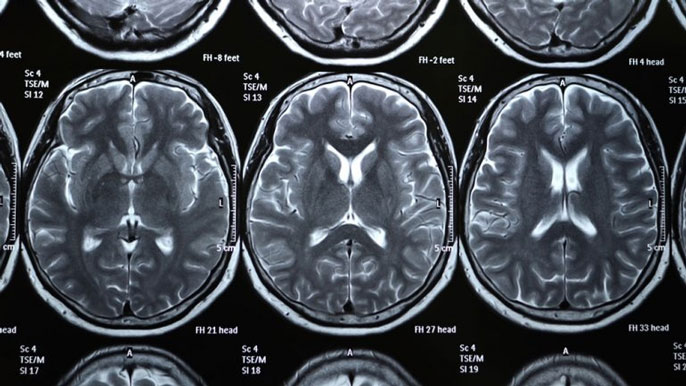

The mechanism in which concussion leads to Parkinson’s is not fully understood, but recent studies have pointed to abnormal brain deposits of a protein called alpha-synuclein in traumatic brain injuries. This protein is a hallmark of Parkinson’s.

Previous research has demonstrated a strong link between Parkinson’s disease and moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury, but this is the first large-scale, nationwide study to show its association with concussion, said first author Raquel Gardner, M.D., of the UCSF Department of Neurology.

For the study, researchers identified 325,870 veterans from three U.S. Veterans Health Administration medical databases. Half of the participants had been diagnosed with concussion or the more serious moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury and half had not. The participants, who ranged in age from 31 to 65, were followed for an average of 4.6 years.

A total of 1,462 of the participants were diagnosed with Parkinson’s, with an average time to diagnosis of 4.6 years. Some 949 of the participants with traumatic brain injury, or 0.58 percent, developed Parkinson’s, compared to 513 of the participants with no traumatic brain injury, or 0.31 percent.

In total, 360 out of 76,297 with concussion, or 0.47 percent, developed the disease and 543 out of 72,592 with the more serious moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury, or 0.75 percent, developed the disease.

More serious brain injuries linked to higher risk

After researchers adjusted for age, sex, race, education and other health conditions such as diabetes and high blood pressure, they found that those with concussion had a 56 percent increased risk of Parkinson’s. As expected, the risk was higher among veterans with the more serious moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury (83 percent).

Researchers also found that those with any form of traumatic brain injury were diagnosed with Parkinson’s an average of two years earlier than those without traumatic brain injury.

“This study highlights the importance of concussion prevention, long-term follow-up of those with concussion, and the need for future studies to investigate if there are other risk factors for Parkinson’s disease that can be modified after someone has a concussion,” said Gardner. “There is increasing recognition that concussion may have long-lasting neurobehavioral consequences, including heightened risk for several psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases.”

Military at risk for unique cause of concussion

Among servicemen and women, concussion may result from exposure to explosives in combat areas. In the general population, it most commonly occurs from falls in older people and motor vehicle accidents and contact sports in younger people.

Parkinson’s affects more than 1 million people in North America, most typically after age 60, according to the National Institutes of Health. It is a progressive disorder of the nervous system that primarily impacts balance and movement.

The study was supported by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Material Command and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs as part of the Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium (CENC), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute on Aging and the American Federation for Aging Research.

The study’s co-authors are Amy Byers, Ph.D., MPH; Deborah Barnes, Ph.D., MPH; Yixia Li, MPH; and John Boscardin, Ph.D., all of UCSF and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center.