Kathleen Maclay, UC Berkeley

Musicologist and Handel scholar John Roberts realized almost immediately that the manuscript he was examining was a new cantata by one of the Baroque masters.

A visit by Dutch conductor and early music specialist Ton Koopman to practice on an organ at a San Francisco church has led to the discovery of a new Handel cantata by a University of California, Berkeley, musicologist.

During one of Koopman’s practice sessions, rector Keith Schmidt of All Saints’ Episcopal Church mentioned that Koopman might like to meet his husband, John Roberts, a Berkeley emeritus professor of music, former head of UC Berkeley’s Jean Gray Hargrove Music Library and a Handel scholar.

Music sleuthing

Schmidt didn’t mention that Roberts is something of a music detective too.

In 1989, Roberts came across the only complete score of Alessandro Scarlatti’s long-lost opera, L’Aldimiro, found in excellent condition on the shelves of the music library. The piece was performed at the 1996 Berkeley Festival and Exposition at UC Berkeley’s Zellerbach Hall. Roberts also reconstructed Handel’s pasticcio, Giove in Argo (Jupiter in Argos), the only one of Handel’s Italian operas for which no score survives.

Credit: UC Berkeley

So last year, after sharing meals and getting acquainted with Koopman, the Dutchman asked Roberts to inspect a copy of music by Handel tucked away in his private library of 17th– and 18th-century music books. He didn’t hesitate to say yes. This sparked the interest of Roberts, who has been drawn to Handel’s music since his high school days.

Koopman’s librarian, Eline Holl, shared the some of the music with Roberts, along with a note that there was something odd about it because it didn’t match the standard catalog of Handel’s cantatas.

“It took only a few minutes,” he said of his inspection of a digital version of the document. “In fact, I realized almost immediately that I was dealing with a genuine alternative setting of an earlier text. I recognized musical ideas found in other Handel pieces while at the same time knowing that I hadn’t seen these particular arias before.”

Roberts said it probably helped that he specialized in the study of Handel’s so-called “borrowing” from himself as well as from other composers.

“I wrote back (to Holl), ‘What you have here is a new cantata,’” Roberts recalled.

Keys to determination

The piece was then brought to London, where Roberts took a closer look at it.

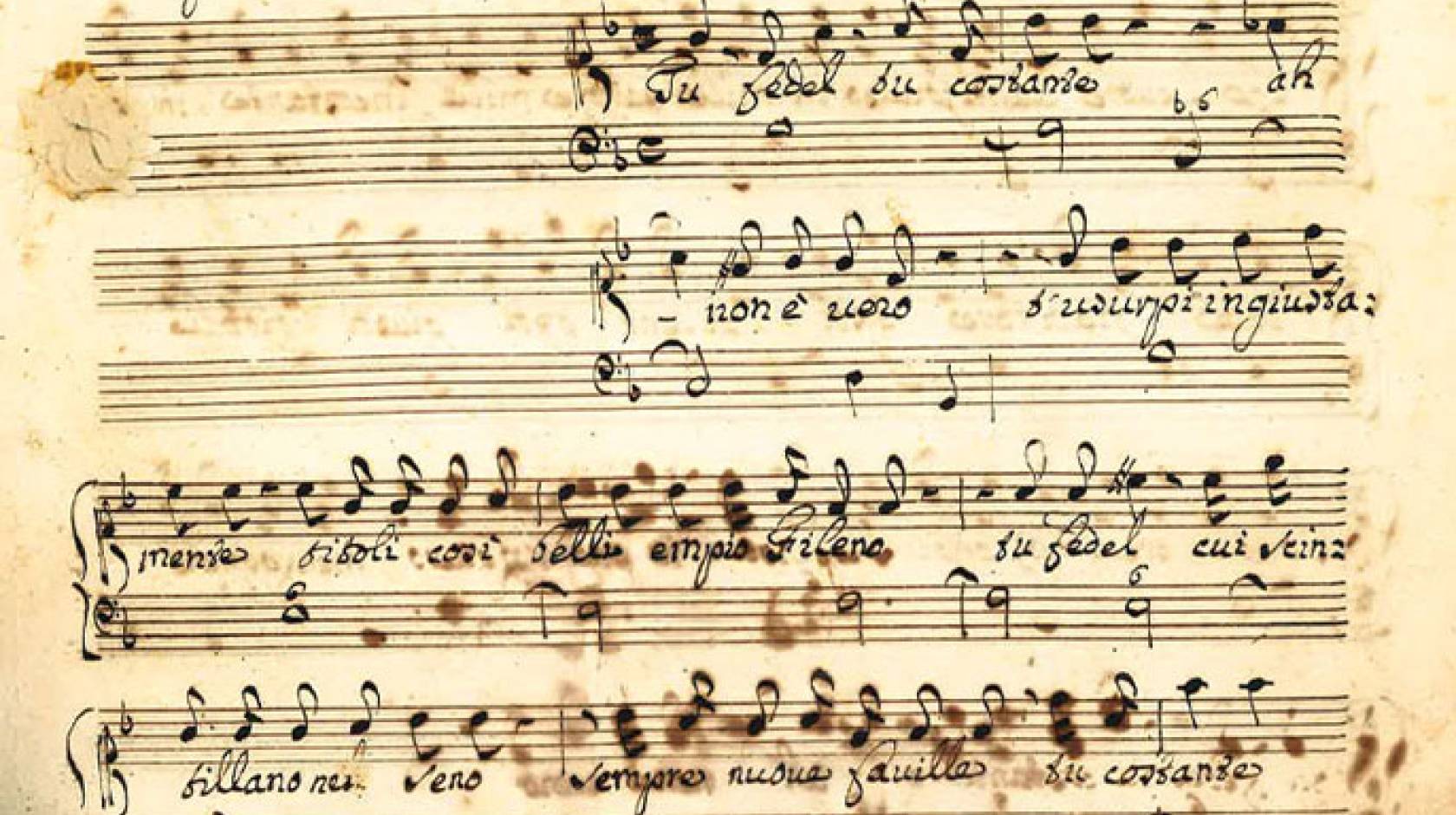

The cantata has four arias, and Roberts found that while the first is essentially the same as in the previously known setting of the Tu fedel? tu costante? text, the remaining three arias are completely different and the scoring for the new cantata includes an oboe in addition to the two violins and basso continuo that are in the other version.

“It’s not different in quality, but very much different in character,” Roberts said. The first version has a sadder tone, while the second is happier and more frivolous.

George Frideric Handel left his native Germany in late 1705 or 1706 to travel around Italy, where he immediately adopted the Italian style. The well-known version of this cantata, HWV 171 in the thematic catalog of Handel’s music, was in existence by May 1707, not long after he moved to Rome. The newly discovered setting of the same text, to be known as HWV 171a, was composed somewhat earlier, probably in Venice or Florence.

“Handel went out of his way to rewrite an earlier work, probably either because of his growing mastery of the Italian style or in order to tailor the music to the strengths of a particular singer,” said Roberts. “His ideas were changing, along with his circumstances.”

Today, Roberts is counting the days until he flies half a world away for an April 9 performance of the 13- to 15-minute-long cantata by Koopman at Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw.

“Handel was an extraordinarily brilliant composer, one of the best in the history of music,” said Roberts. “So everyone of his pieces we find – and we rarely come up with a new one – is a contribution to a repertoire that is a standard part of baroque literature.”