Robin Marks, UCSF

When our eyes move during REM sleep, we’re gazing at things in the dream world our brains have created, according to a new study by researchers at UC San Francisco. The findings shed light not only into how we dream, but also into how our imaginations work.

REM sleep — named for the rapid eye movements associated with it — has been known since the 1950s to be the phase of sleep when dreams occur. But the purpose of the eye movements has remained a matter of much mystery and debate.

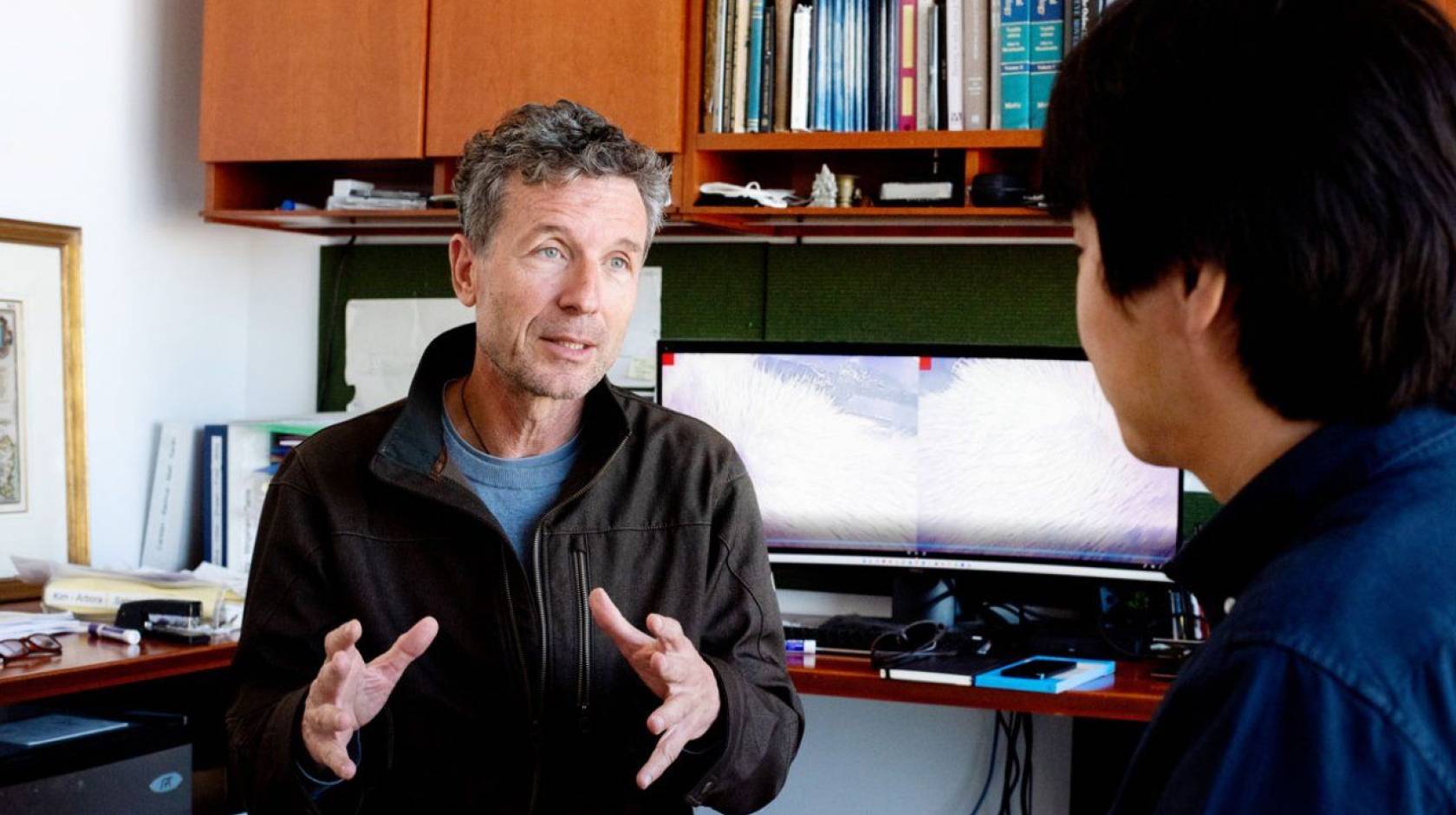

“We showed that these eye movements aren’t random. They’re coordinated with what’s happening in the virtual dream world of the mouse,” said Massimo Scanziani, Ph.D., senior author on the study, which appears in the Aug. 25, 2022, issue of Science.

“This work gives us a glimpse into the ongoing cognitive processes in the sleeping brain and at the same time solves a puzzle that’s triggered the curiosity of scientists for decades,” he said.

Connecting eye movement with dream direction

In the second half of the 20th century, some experts hypothesized that these REM movements may be following scenes in the dream world, but there was little way to test it, and the experiments that could be done (noting a dreamers’ eye direction and then waking them up to ask where they were looking in the dream) provided contradictory results. Many researchers wrote off REM movements as random actions, perhaps to keep the eyelids lubricated.

Given much more advanced technology, Scanziani, along with UCSF postdoctoral researcher Yuta Senzai, Ph.D., were able to look at “head direction” cells in the brains of mice, who also experience REM sleep. These cells act something like a compass, and their activity shows researchers which direction the mouse perceives itself as heading.

The team simultaneously recorded data from these cells about the mouse’s heading directions while monitoring its eye movements. Comparing them, they found that the direction of eye movements and of the mouse’s internal compass were precisely aligned during REM sleep, just as they do when the mouse is awake and moving around.

A perfectly harmonious fake world

Scanziani is interested in the “generative brain,” meaning the ability to make up objects and scenarios.

“One of our strengths as humans is this capacity to combine our real-world experiences with other things that don’t exist at the present moment and may never exist,” he said. “This generative ability of our brain is the basis of our creativity.”

It’s difficult to study this type of brain function, however; it requires looking into the brain while it’s developing new experiences and ideas in the absence sensory input. Dreaming provides just that opportunity.

In a dream, Scanziani noted, you can combine familiar things with the impossible. He described a recurrent dream he had as a young diver, in which he was able to breathe under water. Invariably, he woke up to find it wasn’t true. “But in the dream, you believe it’s real because there aren’t sensory inputs to bring you back to reality,” said Scanziani. “It’s a perfectly harmonious fake world.”

Scanziani’s team found that the same parts of the brain — and there are many of them — coordinate during both dreaming and wakefulness, lending credence to the idea that dreams are a way of integrating information gathered throughout the day.

How those brain regions work together to produce this generative ability is the mystery that Scanziani plans to continue trying to unravel.

“It’s important to understand how the brain updates itself based on accumulated experiences,” he said. “Understanding the mechanisms that allow us to coordinate so many distinct parts of the brain during sleep will give us insight into how those experiences become part of our individual models of what the world is and how it works.”

Massimo Scanziani, Ph.D. (left), and Yuta Senzai, Ph.D. (right).