Robin Marks, UC San Francisco

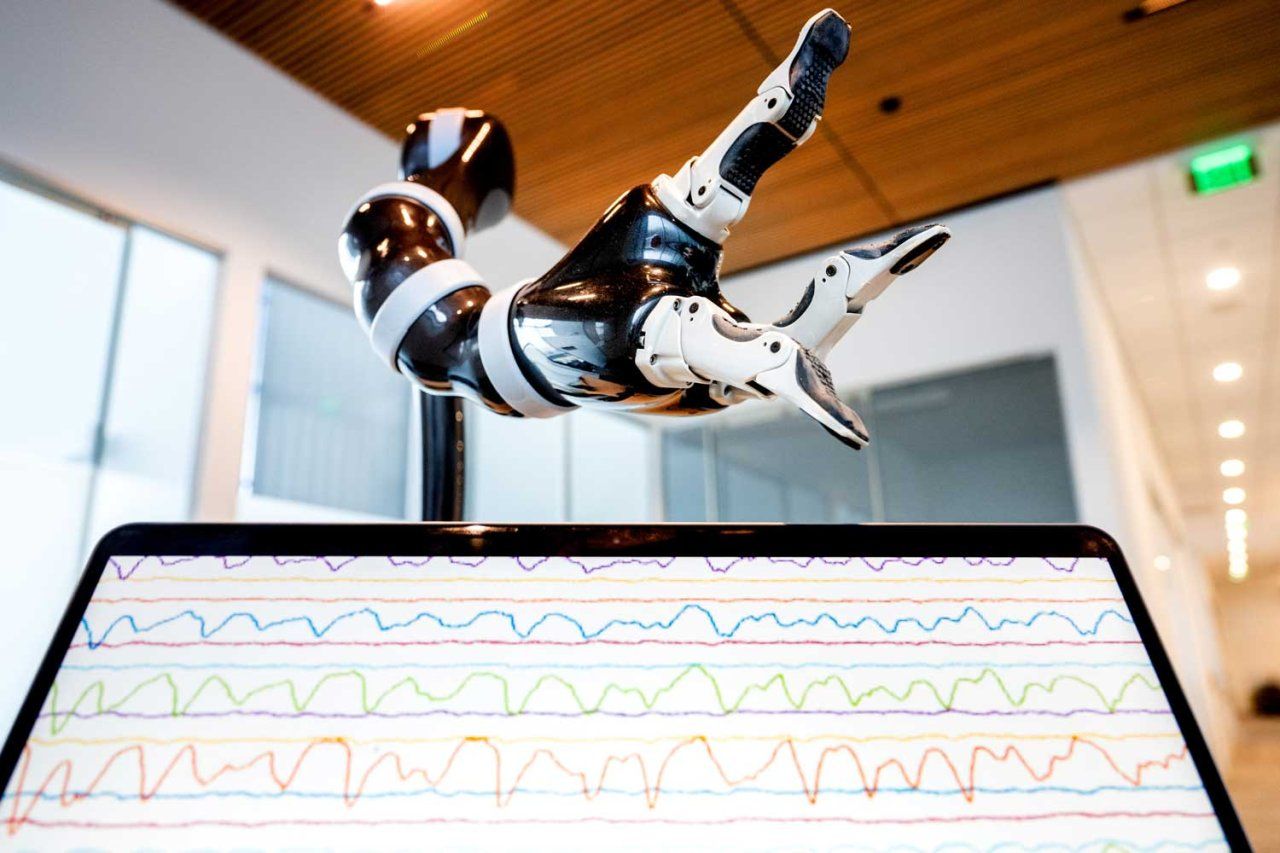

Researchers at UC San Francisco have enabled a man who is paralyzed to control a robotic arm that receives signals from his brain via a computer.

He was able to grasp, move and drop objects just by imagining himself performing the actions.

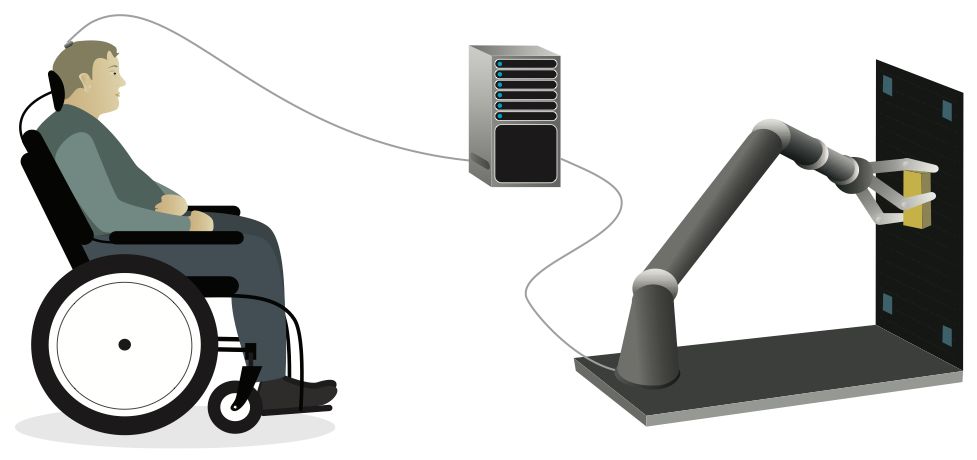

The device, known as a brain-computer interface (BCI), worked for a record seven months without needing to be adjusted. Until now, such devices have only worked for a day or two. The BCI relies on an artificial intelligence (AI) model that can adjust to the small changes that take place in the brain as a person repeats a movement — or in this case, an imagined movement — and learns to do it in a more refined way.

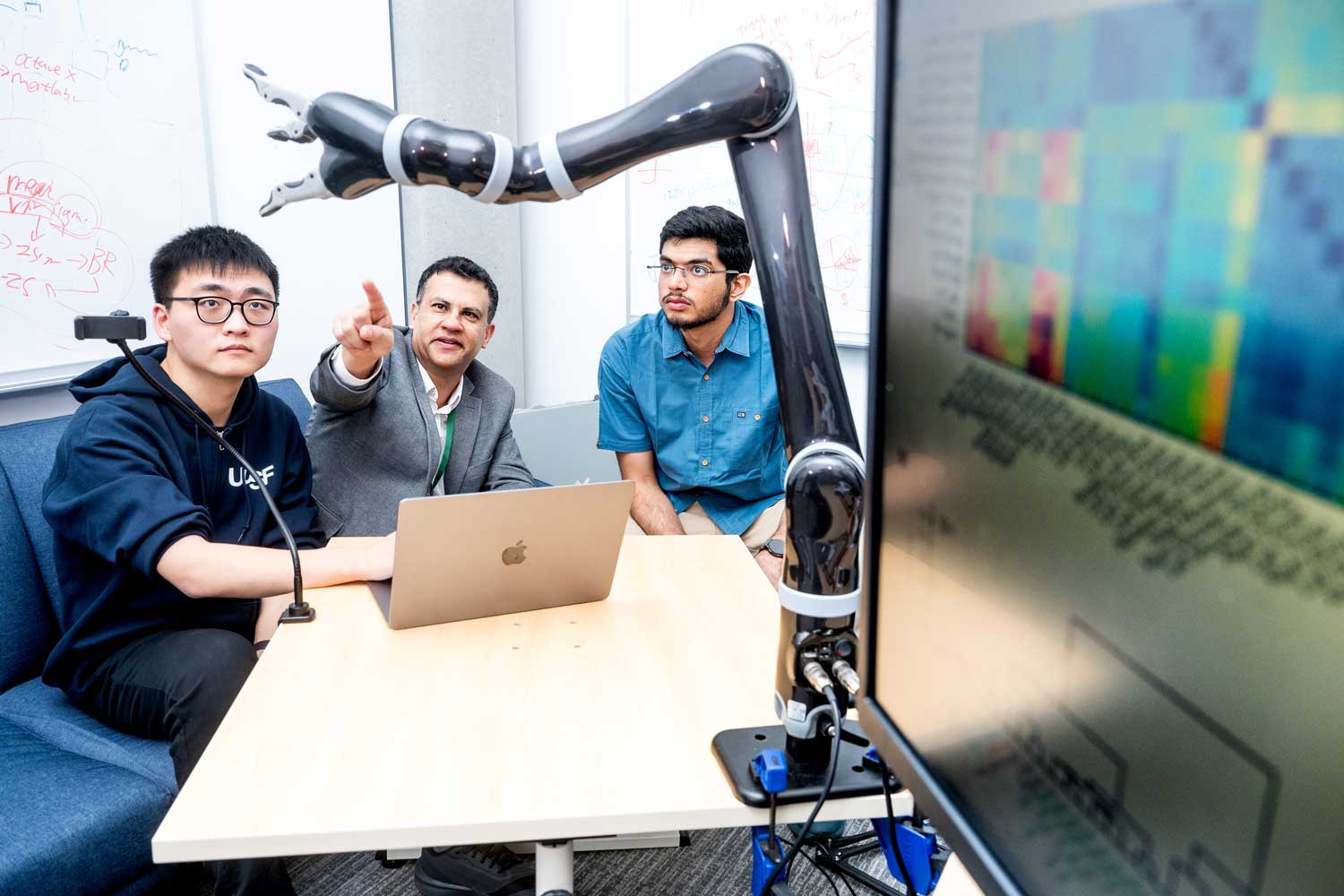

“This blending of learning between humans and AI is the next phase for these brain-computer interfaces,” said neurologist, Karunesh Ganguly, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of neurology and a member of the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences. “It’s what we need to achieve sophisticated, lifelike function.”

The study, which was funded by the National Institutes of Health, appears March 6 in Cell.

Location, location, location

The key was discovering how activity shifts in the brain day to day as a study participant repeatedly imagined making specific movements. Once the AI was programmed to account for those shifts, it worked for months at a time.

Ganguly studied how patterns of brain activity in animals represent specific movements and saw that these patterns changed day-to-day as the animal learned. He suspected the same thing was happening in humans, and that was why their BCIs so quickly lost the ability to recognize these patterns.

Ganguly and neurology researcher Nikhilesh Natraj, Ph.D., worked with a study participant who had been paralyzed by a stroke years earlier. He could not speak or move.

He had tiny sensors implanted on the surface of his brain that could pick up brain activity when he imagined moving. To see whether his brain patterns changed over time, Ganguly asked the participant to imagine moving different parts of his body, like his hands, feet or head.

Although he couldn’t actually move, the participant’s brain could still produce the signals for a movement when he imagined himself doing it. The BCI recorded the brain’s representations of these movements through the sensors on his brain. Ganguly’s team found that the shape of representations in the brain stayed the same, but their locations shifted slightly from day to day.

The illustration below shows how the brain-computer interface (BCI) receives brain signals to decode and allow a study participant to move the robotic arm.

From virtual to reality

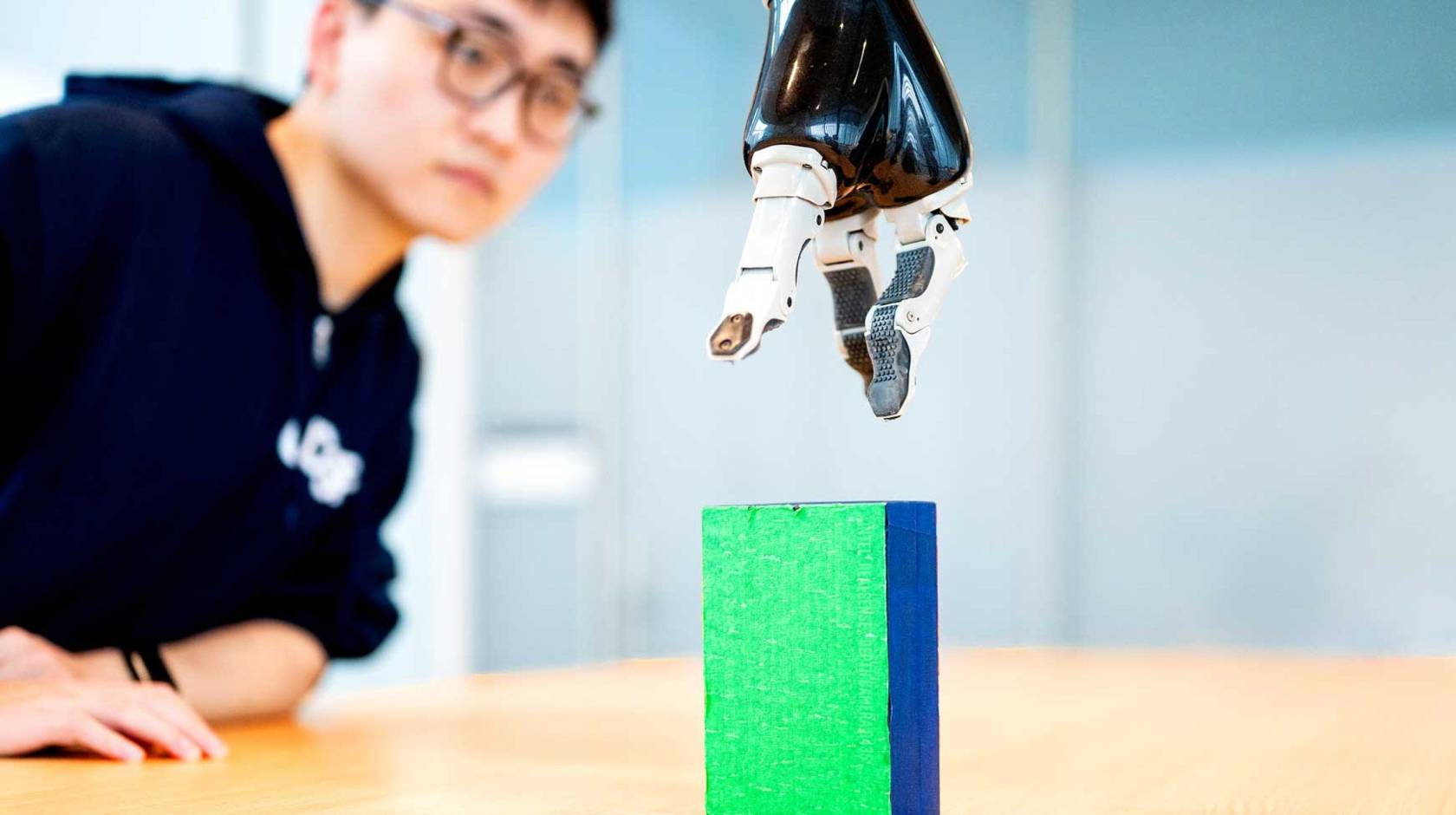

Ganguly then asked the participant to imagine himself making simple movements with his fingers, hands or thumbs over the course of two weeks, while the sensors recorded his brain activity to train the AI. Then, the participant tried to control a robotic arm and hand. But the movements still weren’t very precise. So, Ganguly had the participant practice on a virtual robot arm that gave him feedback on the accuracy of his visualizations. Eventually, he got the virtual arm to do what he wanted it to do.

Once the participant began practicing with the real robot arm, it only took a few practice sessions for him to transfer his skills to the real world. He could make the robotic arm pick up blocks, turn them and move them to new locations. He was even able to open a cabinet, take out a cup and hold it up to a water dispenser.

Months later, the participant was still able to control the robotic arm after a 15-minute “tune-up” to adjust for how his movement representations had drifted since he had begun using the device.

Ganguly is now refining the AI models to make the robotic arm move faster and more smoothly, and planning to test the BCI in a home environment.

For people with paralysis, the ability to feed themselves or get a drink of water would be life changing.

“I’m very confident that we’ve learned how to build the system now, and that we can make this work,” Ganguly said.

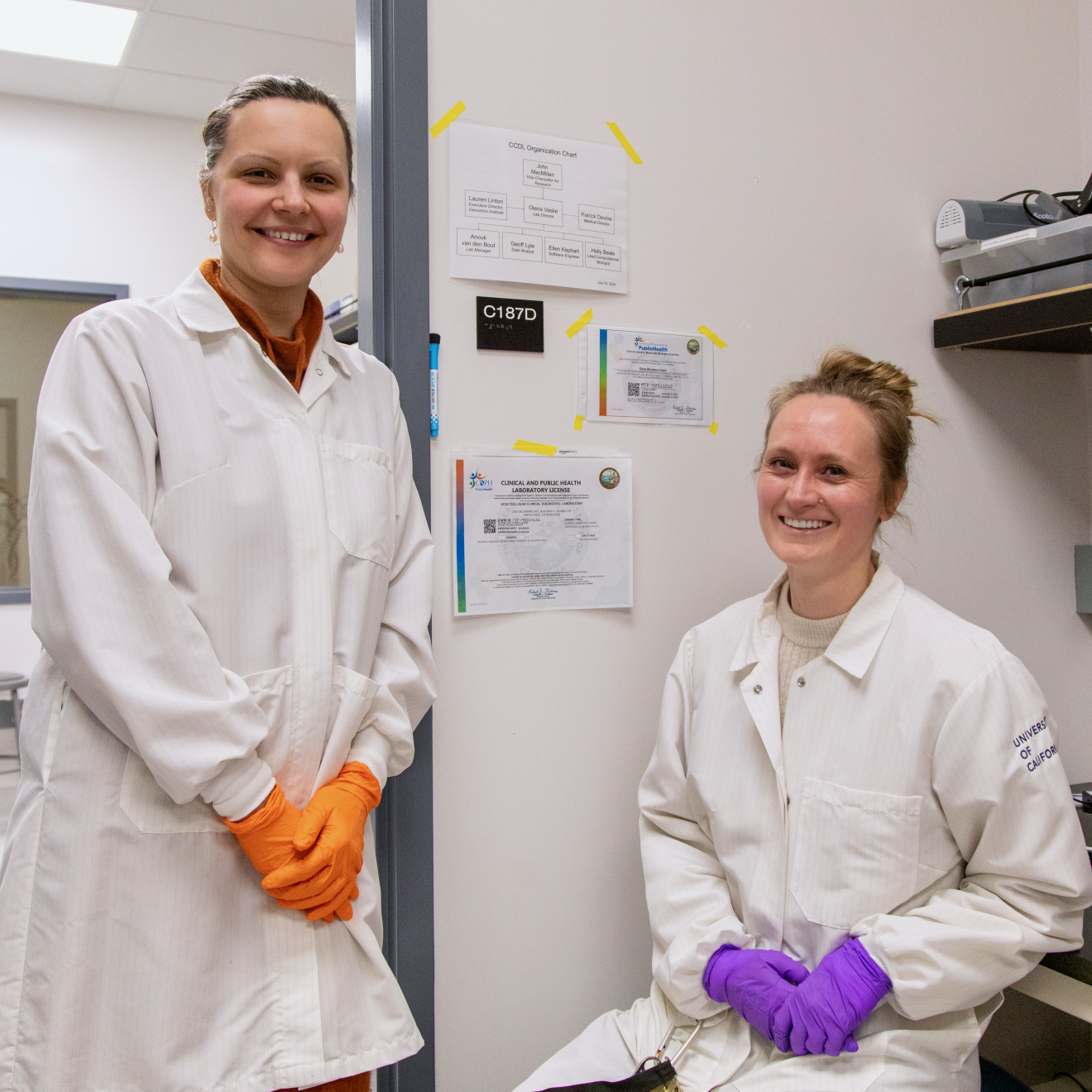

Authors: Other authors of this study include Sarah Seko and Adelyn Tu-Chan of UCSF and Reza Abiri of the University of Rhode Island.

Funding: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (1 DP2 HD087955) and the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences.