Jessica Wolf, UCLA

A funny thing happened in the esoteric world of philosophy in late 2016 — professors and students were buzzing on social media about a sitcom.

Is there really a television show that muddles through questions like “Is it ever OK to lie?” and “Is morality judged on results or intentions?” And even more surprisingly, how is this mainstream network TV show getting these debates so right?

That show is “The Good Place,” which debuted on NBC in September 2016 and whose third season opened Sept. 27. The show picks up the story of a young woman immediately following her untimely death by shopping cart. Eleanor Shellstrop, played by Kristen Bell, is greeted in the titular Good Place by Michael, an immortal magical being played by Ted Danson. But Eleanor, who in life was capricious at best, maniacal at times and nearly always frivolous with the feelings and needs of others, immediately realizes there’s been a mistake. And worse, there’s another Eleanor Shellstrop who’s suffering for the heavenly clerical error over in “the bad place.”

The premise created a fertile ground for all kinds of questions about what makes one person “good” and another not. What actions and decisions should and can be rewarded? And why? And how?

As for how the philosophically grounded afterlife fantasy-comedy is getting things so right? Part of the reason is that UCLA philosophy professor Pamela Hieronymi was an early consultant on the show.

She met for several hours the year before shooting began with show creator Mike Schur (creator of “Parks and Recreation”) for a wide-ranging conversation about free will, moral responsibility, ethics and how much agency human beings actually have over their own attitudes, intentions and actions — all of which inform her research and teaching.

“He was just working on the first scripts and I walked him through the thematic side of concepts and abstract conflicts while he was thinking about how those would apply to storylines and characters,” Hieronymi said.

Hieronymi said she gets requests like this every so often, though typically they’re lower profile — a grad student working on a film. She agrees to such meetings whenever she can, because they typically engender an interesting conversation.

“And then, I nearly missed our appointment, I was like the absent-minded professor,” she joked. “But he was really nice about it. He wanted to know how someone who is trained the way I am would think through the issues that he wanted to address in his show. It’s really fun to encounter someone who is extremely interested in the things I am, but is coming at them from a very different way of thinking.”

‘The Trolley Problem’

Credit: Gerard Vong/UCLA

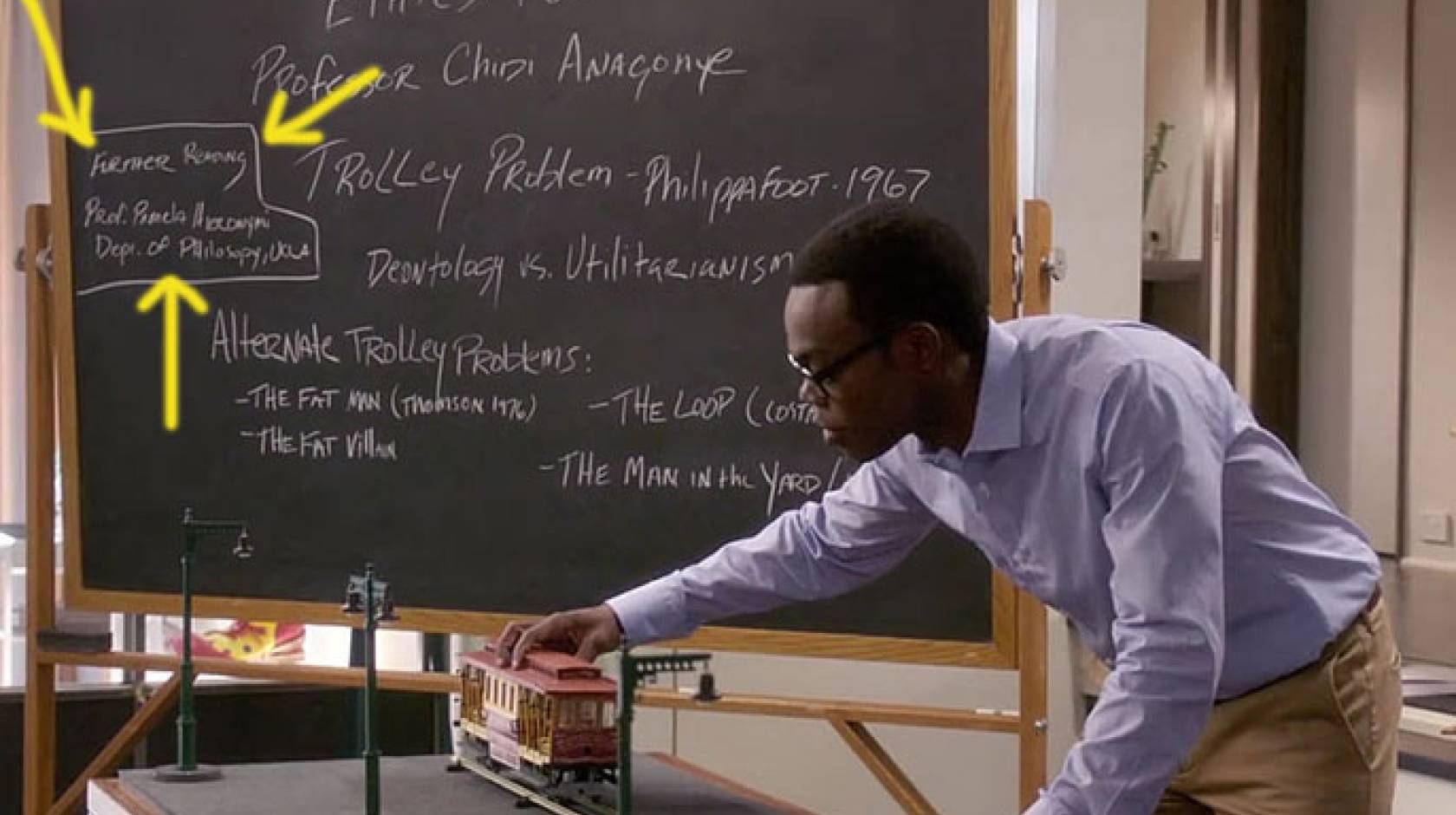

One of the standout examples of the show incorporating the conundrums of moral and ethical philosophy occurred during a season two episode. Hieronymi visited the show’s writers room to help explain the classic consequentialism thought experiment known as “The Trolley Problem.” In this scenario, a person must ruminate on the what they would do if they were on an out-of-control train that they cannot stop. They only thing they can do is switch the train from one track to another. On one track there are five workers, oblivious to the oncoming train. On the other there is just one person. Is it better to turn the train and only harm one? Is this a deceptively simple problem?

Hieronymi worked through all the variations of the puzzle and the questions that people sort through as they attempt to predict how they might hypothetically react — do you know any of the people who would be killed? Is the person alone on the second track a life-saving surgeon? The show used special effects and the magic of television to vividly illustrate how some of those reactions and decisions might play out.

“The Trolley Problem is a good opener, it’s what I open my introductory course with actually,” Hieronymi said. “It’s a good way to immediately get people to see that the way they think about things sometimes doesn’t fit together. You can get them to say right away — keep five people alive and sacrifice the other one.”

But then you start layering in things like the surgeon variation, and it gets people thinking about how their sense of why certain things are right or wrong is off, she said.

As the show moved into its second season, Hieronymi said it was interesting to watch the unfolding of some of the broader topics she and Schur originally discussed, like the ideas of shared fate and what humans owe one another if they’re trying to live morally and ethically.

Philosophical decisions occur in everyday life

Olúfẹmi O. Táíwò was alerted to the existence of “The Good Place” while he was a Ph.D. candidate in philosophy at UCLA and friends started telling him that there was a show with a character that was just like him. Eleanor’s afterlife soulmate, Chidi (played by William Jackson Harper), was an ethics professor when alive. Chidi teaches Eleanor moral and ethical philosophy so she can genuinely earn her spot in the Good Place. Táíwò was skeptical at first, but soon saw the character similarities — and the larger potential of the show.

“A lot of times I find myself struggling to convince my students that they are always involved in something that is relevant to philosophy, whether or not that is the term by which they are doing it,” said Táíwò, who is now an assistant professor of philosophy at Georgetown. “And now, here’s this world that the show has built where almost every plotline ties into a philosophical question.”

Táíwò likes how the show has obliquely tackled religious themes as moral imperatives, and the questions about nature versus nurture the story elicits.

“And now we’re essentially in a reincarnational plotline,” he said. “Michael makes this point toward the end of season two, this point of why should a human’s time on Earth be the only time that’s relevant to assessing the immortal soul?”

When it comes to thought experiments, Hieronymi prefers what is known as Kavka’s Toxin Puzzle, created by Gregory Kavka, who taught at UCLA in the late 1970s. An eccentric billionaire offers you $1 million dollars if, at 10 p.m. tonight, you decide that tomorrow at noon you will drink a poisoned cocktail. It will make you sick, but not kill you. The billionaire has a magic device that can unequivocally discern whether or not, at 10 p.m., you sincerely intend to drink the poison. But you don’t actually have to drink the poison to get the money. It will appear in your bank account as long as the intention is true. But knowing that you don’t have to actually drink it, can you in fact intend to drink it?

This relationship between intention and action is at the heart of Hieronymi’s current scholarship.

Hieronymi, who has been a professor at UCLA since 2000, teaches a course on ethical theory, and courses in free will and moral responsibility. She’s working on a book titled “Minds that Matter,” which will explore the ways in which the kind of control humans have over their own minds, intentions and fears is not the same kind of control that we have over our actions.

In the meantime, Hieronymi will continue to watch “The Good Place,” and enjoy another interesting element of the show — the way in which Schur and the writers have tapped a broad spectrum of philosophical ideas for comedy fodder.

“It looks like the show its running at two levels — obviously incorporating Plato and Aristotle and Kierkegaard and Hume and Kant — all the big canonical figures,” Hieronymi said. “But they’ve also found creative ways — even in just little bits of dialogue or set design — to include contemporary thinking from figures like Thomas M. Scanlon and Jonathan Dancy and Todd May. It’s extremely fun to see that philosophy ‘product placement’ in there.”