The endangered blue whale is the largest animal to have ever lived on Earth — let alone California.

At up to 400,000 pounds (the weight of 33 elephants!) and as long as 90 feet, they migrate up the California coast from May to October alongside several other species, including humpbacks and gray whales, favorites of whale watchers. But unlike those two species, the blue whale has never come close to recovering from the devastation of 20th century commercial whaling, banned internationally in 1986.

Even the biggest animals need help in our changing oceans. As many as 80 endangered whales — among them blue whales, fin whales, and some populations of humpbacks — wash up on California shores each year, often after fatal encounters with container ships. Ship strikes are a top source of whale mortality, killing thousands of whales globally each year. It’s a worsening problem that has even prompted federal investigation by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Every whale loss matters, not just for biodiversity and the loss of cherished individuals — some of whom are bona fide celebrities — but because we run the risk of losing some of these magnificent species forever.

UC Santa Barbara marine biologist Douglas McCauley has good news.

“This is a solvable problem,” he says.

He and his team have developed a solution for alerting ships to the presence of whales so they can slow down and take precautions. Even better: Two years of data suggest it’s working.

With fewer than 15,000 blue whales worldwide, and just 2,000 off the California coast, we can, and must, save the whales.

Falling for the oceans

McCauley grew up in Los Angeles, maybe not the most obvious place to discover a passion for ecology. The sidewalks and built environment of LA were not a natural showcase, but the yawning blue space on the map beckoned.

“For the price of a $15 entry ticket, which was your mask, you could dive underwater in a kelp forest, look up and see the skyline of LA, the zooming cars, then look down and share space with giant sea bass and migrating whales,” he says. “Wildness was waiting for me as a teacher, my earliest lab.”

Douglas McCauley

Working on fishing boats going in and out of the Port of Los Angeles in the summer helped him pay his way for a degree at UC Berkeley. Many of the people he grew up with had family working in the port as longshoremen or worked there themselves. The importance of the towering shipping industry to local families and communities was unmissable, as was its vital role in the overall economy.

“Some people estimate that 80 to 90 percent of the goods that we interact with on a daily basis have actually traveled on a ship across an ocean somewhere,” McCauley notes.

Thousands of container ships and tankers ply our waters each year, a $9 billion industry that continues to grow. The danger to whales has grown with it, even as scientists continue to uncover profound insights about whale intelligence and communication, and the vital role these mammals play in the health of ocean ecosystems.

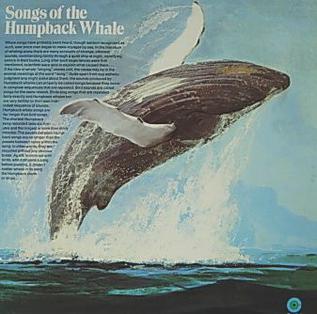

The songs that changed the world

In the 1960s, when commercial whaling was taking as many as 50,000 whales a year, long after the usefulness of their blubber as a natural resource had expired, scientist Roger Payne was listening to something. Naval equipment called hydrophones monitored the seas, hoping to detect stealthy enemy submarines. But they were also detecting strange underwater sounds that they couldn’t identify. Payne was the first to realize the noises chalked up to mechanical objects were actually whale vocalizations, and more than that, songs they used to communicate. In 1970, he introduced the world to these songs through his best-selling LP “Songs of the Humpback Whale.”

Payne’s scientific discovery helped launch advocacy against commercial whaling and the ubiquitous 1970s campaign to “save the whales.” And it worked — commercial whaling was banned internationally in 1986.

Since that time, and because some whales have been able to recover somewhat, we’ve made even more discoveries. Whales don’t just sing — they have unique dialects that vary within species and pods. Some scientists, among them UC Berkeley faculty, are even trying to understand their language, and possibly “speak” it, as part of an international effort involving endangered sperm whales. We’ve learned that whales grieve, will protect other animals from predation, and may even hold secrets to aging and resilience against cancer. Science’s growing recognition of their complexity reflects the appreciation many Indigenous communities have had for whales going back millennia.

The big elephant in the room — or blue whale, if you will — is that we’ve also just begun to learn how important they are in combating climate change: A single whale sequesters about as much carbon as 1,375 trees when it is able to die naturally and sink to the ocean floor (a lengthy process known as “whale fall”). Even whale poop has value, stimulating the production of phytoplankton, which captures 40 percent of all CO2 on Earth. Today, whale populations as a whole are at just a quarter of their pre-whaling numbers — yet they could be a powerful tool against global warming.

But for all their tremendous size, complexity and impact, even the biggest whales are no match for global shipping.

Everyone’s best interest

While a blue whale at nearly 100 feet is the biggest animal ever recorded on the planet, container ships are at least 13 times their size. Traveling at high speeds, container ships also produce a ton of noise, overwhelming whales’ ability to communicate as they pass through. Picture trying to have a conversation in a crowded bar, McCauley says. Then imagine that midway through the conversation, you suddenly have to come up for breath — that’s when whale strikes happen.

The front of a ship is actually quieter than the rest of it, so when whales head up for oxygen and relief, that’s when they get hit. The strikes don’t hurt the ships, but they pulverize the largest animals on Earth.

“Nobody wins when they come into the harbor with a beloved species wrapped around the bow,” McCauley says. “It’s in everyone’s best interest to avoid this. One of the recommendations from industry was, just tell us when they’re there.”

“We can’t teach whales to avoid ships,” McCauley says. “But we can change shipping.”

A “school zone” for whales

Research has shown the danger to whales is much lower when ships proceed at speeds of 10 knots or less. Unfortunately, as whales migrate in search of a krill buffet, they share their habitat with container ships navigating shipping lanes. There are speed limits, but on the West Coast, compliance is voluntary — and a 2019 study found that less than half of ships comply.

Voluntarily slowing down while your competitors keep trucking is a precarious scenario in the global economy. So McCauley and his team, including colleagues at UC San Diego and UC Santa Cruz, developed a way of producing real-time information on the presence of whales so ships will voluntarily slow down. McCauley compares the tool, known as “Whale Safe,” to the traffic rules that reduce speeds when kids are getting out of school.

Whale Safe works by synthesizing a few data sources into one assessment. Far beneath the surface, a hydrophone — that naval instrument through which Roger Payne revolutionized whale science by analyzing their calls for the first time — listens for whale calls in the nearby area, which are identified by a computer as blue, fin or humpback (the first two species are particularly endangered). Naturalists on whale watching ships also provide data of real-time whale sightings at the surface and transmit that back to scientists at Whale Safe. Data on whale migration patterns is then incorporated through artificial intelligence to analyze the likelihood that whales are in a given area at any time.

It all comes together to form a “whale presence” rating that shipping companies can follow as their vessels pass through the Santa Barbara Channel and the San Francisco Bay Area, the state’s major shipping hotspots.

Whale Presence Rating: HIGH

— Whale Safe – Southern California (@whalesafe_sc) October 6, 2022

Acoustic Detections: Humpback, Blue, Humpback.

Sightings: 0 Blue, 13 Humpback, 0 Fin.https://t.co/qrI7CWx3ud pic.twitter.com/Azl9xKrQdv

Right now, compliance with these slow down programs is voluntary, so while many shipping companies do comply — and many genuinely want to help — they aren’t legally bound to do so. But the ratings and compliance are also made available to the public in real-time by Whale Safe, creating an environment where pressure and accountability can be applied to companies that don’t change.

It’s just a start on an international problem, but there are encouraging signs that it works. From 2018 up til the launch of Whale Safe on September 17, 2020, Southern California recorded 10 ship strikes, 6 of those fatal. But in the 2 years that Whale Safe has been in place in the Santa Barbara Channel, McCauley says no ship strikes have been recorded at all.

The system is now being tested in the San Francisco Bay, with the goal of showing that the system and its equipment can overcome the challenges of different marine environments.

“Elon Musk says things are hard in space,” McCauley chuckles. “I don’t begrudge our space community, but sharks biting your tools is hard, too.”

McCauley envisions the system evolving into something similar to Dolphin Safe tuna, with brands advertising that they use the tool to safeguard whales, and consumers rewarding that practice with increased sales.

Keeping whales safe from shipping strikes is an important way of helping their populations rebound, which could also help us fight climate change.

And there are other steps we can take to protect these animals. UC San Diego’s Scripps Whale Acoustics Lab, an important partner on Whale Safe, is working on reducing ship noise and rethinking ship design. Private donors are helping this important work expand. The Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory that McCauley directs, based in UC Santa Barbara, is part of a $60 million gift from Marc and Lynne Benioff to safeguard ocean health through science and technology. Whale Safe is one tangible result of that investment.

Climate change is the other major threat to whales, and one that looms even larger than ship strikes, McCauley says. Whales are adaptable, but to continue their population growth and vital role on the planet, they’ll need some human help. Fortunately, there are thousands of students who — just like McCauley — are passionate about protecting and preserving not only the world’s largest animal, but the entire ecosystem that it helps power.

“There's a lot of environmental trauma out there,” McCauley says, “but I find in my classrooms hundreds of students that are looking to engineer a better future and figuring it out with their hearts and with their minds. And these brilliant students will be the architects of some pretty brilliant innovations.

They’re gonna blow what we’re doing with Whale Safe out of the water.”

To learn more about UC Santa Barbara’s efforts with partners at UC Santa Cruz, UC San Diego, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Oregon State University, University of Washington, NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center, Conserve IO, The Marine Mammal Center, Point Blue Conservation Science, and Cascadia Research Collective to track whale and shipping activity to provide the best available science to reduce the risk of whale-ship collisions, visit the Whale Safe website.

You too can listen to the songs of the humpback whale on Bandcamp.