John Hickey, UC Berkeley

Paula Raffaelli has had almost four weeks to process the one week she spent in December in Dilley, Texas.

The processing goes on.

Raffaelli, a complaint resolution officer with UC Berkeley’s Office for the Prevention of Harassment and Discrimination, spent the week putting her lawyering skills to work on behalf of immigrant women and children in the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s detention facility in Dilley.

Courtesy Paula Raffaelli

“It is hard to sum up just what that experience was,” Raffaelli says. “It was emotional, exhausting, inspirational, frustrating and intense. And more. It was everything you could imagine.”

She was one of dozens of attorneys volunteering with the CARA Family Detention Pro Bono Project, commonly referred to as the Dilley Pro Bono Project. She and her husband, Mario Ochoa Villicana, made the trip with the help of some Facebook crowdsourced fundraising with Mario along to serve as translator.

“What I can tell is that going there, my expectations were that it would be pretty horrible,” Raffaelli says. “My expectations were met, and then some.

“Dilley is a jail. They call it a detention center, but it’s a jail. And their detention area before getting to Dilley has holding cells the women call las hielera (icebox) that are kept at a very cold temperature. The reason given is that the cold is to keep disease out, but almost every woman and child we saw was suffering from some illness or another. Many of the children had a very deep cough,” says Raffaelli. “These are people who have been through a harrowing journey, and that could be the reason for the illness, but they don’t like the ice box.”

On the Thursday of her week in Dilley, news broke of the death of Jakelin Caal Maquin, the 7-year-old Guatemalan girl who died Dec. 8 of illness while in U.S. custody, and Raffaelli said that news “was impactful” on everyone.

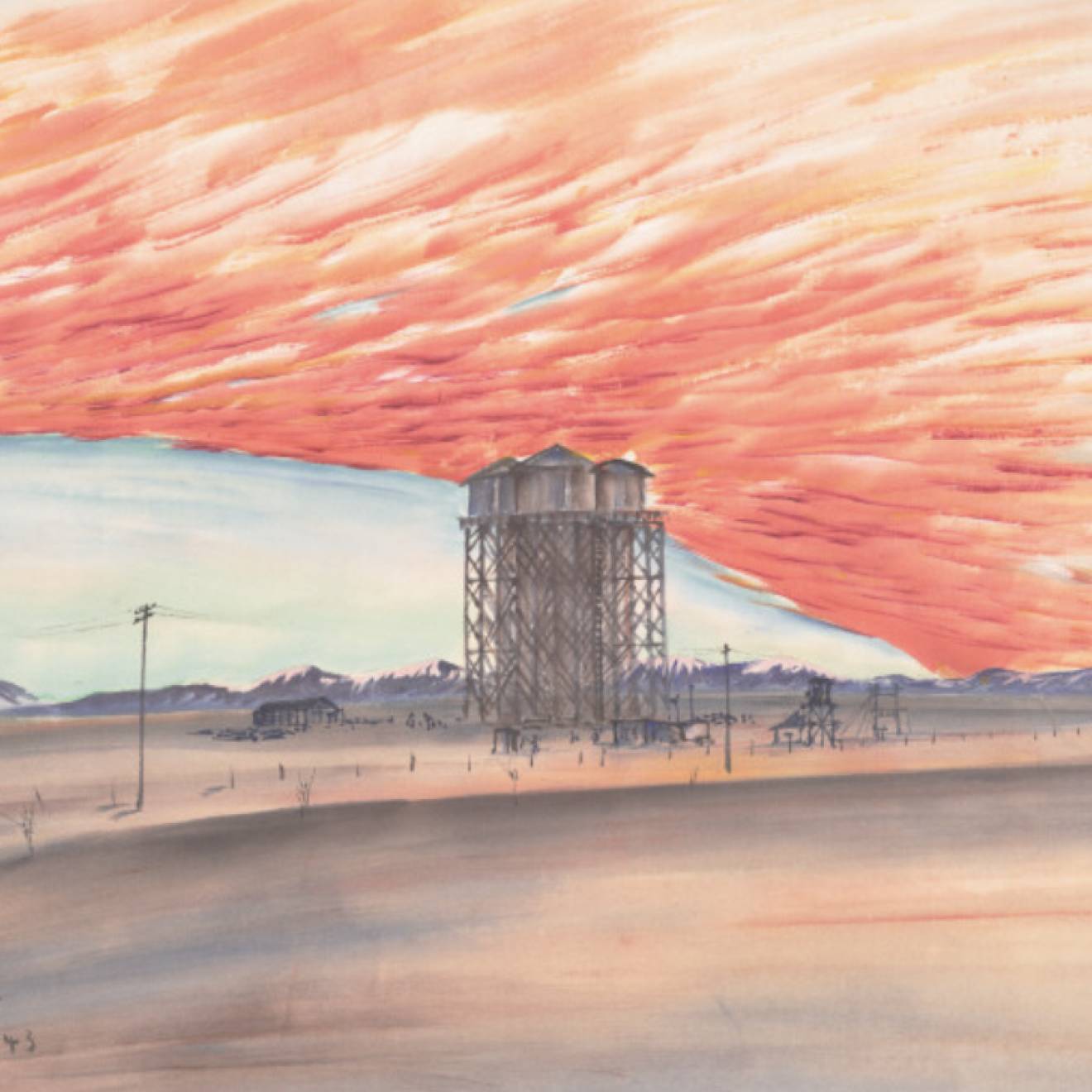

Dilley, Texas is home to lawyers from around the country for a week at a time, including Paula Raffaelli of UC Berkeley.

While she was there, Raffaelli kept a daily journal that chronicled the ebbs and flows of her 12-hour days. She’s agreed to share the journal, which was originally posted on the crowdsourcing site.

Monday, Dec. 10

Day 1 at the South Texas Family Residential Center (the immigration detention center in Dilley) is complete. It was intense, and I have a lot to process. But you all must know that these women are absolute warriors. They have been through hell and they’re still going through it.

They sat through long interviews with us painstakingly detailing their trauma, preparing for their interview with an asylum officer that will decide if they can get out of detention. Some talked to us with babies sleeping in their arms. And some talked to us with the background sound of children crying or coughing.

That background noise is ever-present with me today and punctuates every moment with a reminder that family detention is inhumane. These kids should not be in jail!

Ending day 1 exhausted.

Tuesday, Dec. 11

Day 2: More manageable, in no small part because we had a better idea of what we we’re doing. What are we doing? Here goes:

7:30 a.m.: Get to the detention center, go through security and head into the visitation trailer in the detention center compound. Immediately assist with one of two groups: the intake group, or the credible fear interview (CFI) group.

The intake group are women who have recently arrived at the detention center. We explain who we are, help them fill out forms and answer many preliminary questions they have about what’s coming next.

The CFI group are women who have been detained for a while and who finally have a pending credible fear interview with an asylum officer in the next day or two. After they get a brief presentation about the asylum process, the volunteer attorneys call out their name from a sign-in sheet, then meet with them in a private room inside the visitation trailer to talk through their case.

These two group presentations happen several times a day, with a new group of women coming in every other hour or so. Each day dozens of women come through the trailer.

8 a.m.-7:15 p.m.: Meet with women to discuss their cases and better understand why they fear returning to their country of origin. Help them to articulate painful trauma that they’ve often never shared with anyone, let alone with total strangers. Provide lots of tissues and support through lots of tears. Still hear dozens of kids crying or coughing in the background — or in the room with you, tugging on their mom’s shirt.

Throughout this process we frequently check in with the full-time Dilley Pro Bono Project staff (which includes lawyers, paralegals and program coordinators) with our 5,000 questions about process, forms, asylum requirements, etc. They are all young, bilingual (at the least), incredibly smart and incredibly patient.

I think each volunteer is meeting with anywhere from two to five women a day. Some of the prep meetings are relatively brief, others can take hours. We’re taking notes and entering pertinent information into an online case tracking system, which allows for a new crop of lawyers to track cases from week to week. We eat lots of snacks in the permanent pro bono office set up in the visitation trailer, or maybe escape for an hour for lunch at nearby restaurants boasting large signs displaying, “WELCOME HUNTERS!”

7:30 p.m.: Leave the detention center, head back to the hotel and COLLAPSE. (Or finish entering case notes into the online tracking system ... then collapse).

Wednesday, Dec. 12

Day 3: I’m just spent. Totally spent. And I didn’t leave an abusive husband and abject poverty and rampant gang violence. I didn’t start my time in America in the hielera (icebox), the Customs and Border Protection holding cell kept at freezing temperatures, where many of these mothers and children slept on concrete slabs, often still wet from crossing el rio. And I didn’t spend 20 days in jail with my child, and I didn’t have to get grilled by some random lawyer about my whole damn life while my child slept, utterly exhausted, in my arms.

The majority of immigrants show up for their asylum hearings. They don’t need to be detained. These aren’t violent criminals. These are tired moms with sick children, looking for a better future.

Thursday, Dec. 13

Courtesy Paula Raffaelli

Day 4: Here’s an asylum law 101 primer to help better understand what’s going on here at Dilley. I’ll just give the most common case, though of course there are always variations.

Most of the women have been apprehended at the border, typically crossing without inspection (i.e., not at an official port of entry — many families feel they have no other choice, because of frequent incidents of border officials turning asylum-seekers away at ports of entry, despite their right to enter there).

Typically, when they’re apprehended, border patrol asks them if they fear returning to their country. If they say yes, they’re “triggered for fear” and they’re given a date for their credible fear interview (CFI) with an asylum officer. Most of what we’ve been doing is preparing them for that interview, where they’ll have to convince an asylum officer they’ll be persecuted on account of a protected ground (race, religion, political opinion, etc.) by their government, or a group the government can’t or won’t control.

At the interview, they can have an attorney with them, though most do it alone. And in any event, attorneys cannot speak for the women other than giving a brief closing statement. If the asylum officer determines they don’t have a credible fear, they can appeal to an immigration judge (IJ) to review.

Today I shadowed a staff attorney at one of those review hearings at a makeshift court at the detention center, with the judge on video. It was the most emotional moment of my week so far. If the IJ affirms the asylum officer decision, there is no right to appeal. You’re pretty much out of luck, and will probably be sent back to your country.

If the asylum officer determines they have a credible fear, their case is referred to an immigration judge for a full hearing. They’re then let out of detention and can reunite with family members waiting for them in the United States.

But you’re not done! You’ve still got to bring your asylum claim to an IJ within a year. At the IJ hearing, they’ll testify about their persecution, and be questioned — sometimes grilled. Hopefully they’ll have an attorney, but not all do. At these IJ hearings, the women do not have the rights of a full court hearing, and judges sometimes do not allow the attorney to speak at all. Most of the women we’ve met this week will make it past the asylum officer stage, but are not likely to make it past this IJ stage. They’ll be denied asylum and ordered removed and sent back to the place they just went through hell to get away from.

If the IJ denies their claim, and if they have the means (they probably don’t), they can appeal it up to a federal appellate court, like the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, where I used to work. Then some staff attorney will read the cold written record of the whole journey, and recommend whether to grant or deny their claim. That’s before moving right along to the next case, because staff attorneys have quotas to meet.

These past four days have vividly brought to life the names from that cold paper record I used to review as a staff attorney so many times. It’s been an honor to finally meet some of these strong women in person, and I’m so grateful and humbled to have been given the chance to do so. I know many of them won’t ultimately meet the stringent legal requirements for asylum, but if we can help them get their kids out of jail, and show them some compassion, it’s worth it.

Friday, Dec. 14

Day 5: Last day in Dilley. What an experience! I’m mentally and emotionally fried, and also two margaritas deep after a “debrief meeting” at Garcia’s Bar & Grill in Pearsall, Texas, (20 min from Dilley) with about half of the volunteer group, so no profound thoughts tonight.